|

I became familiar with Anne McGrath's works when I ran Working On Gallery's Instagram account. During the pandemic, she posted a piece every day -- some were black & white paintings, some were naturistic adaptations -- it became my morning routine to observe her art with a cup of coffee.

Today's process essay especially encourages me because I have been thinking of how much I have yet to achieve in creative writing. During the pandemic, I was really thankful and lucky to survive as a poet & artist. Though, I also realized that I was becoming a professional creator who has to be flexible under many circumstances. I likely burned out, because my mind told me, "I don't want to read or write in English anymore!" "Then the pandemic lock-down hit and I found myself at home with time and a small tray of my son’s leftover watercolors, crayons, and markers... At the risk of making a fool of myself I posted one of my creations on Instagram." I would like to express McGrath was a nonfiction writer. She started painting when the pandemic started about two years ago.

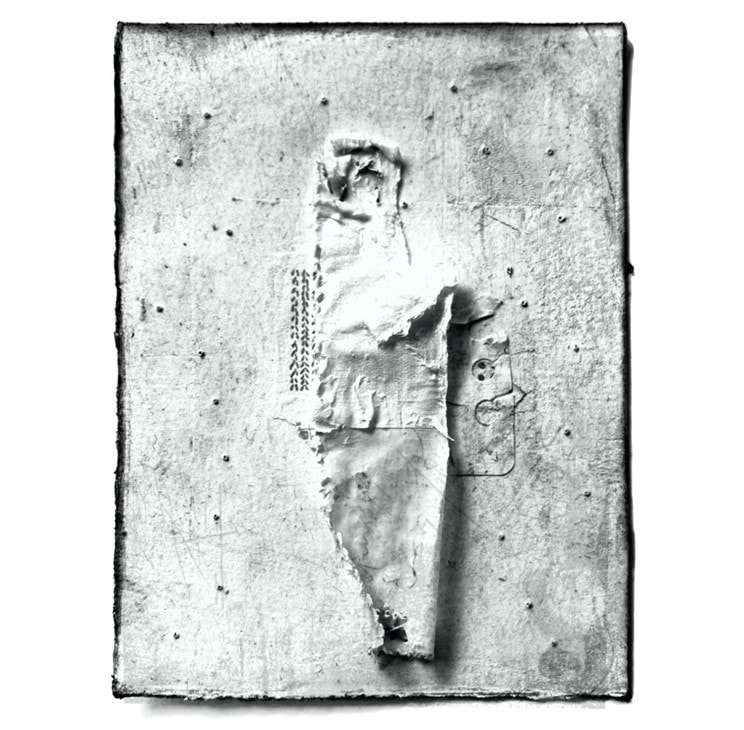

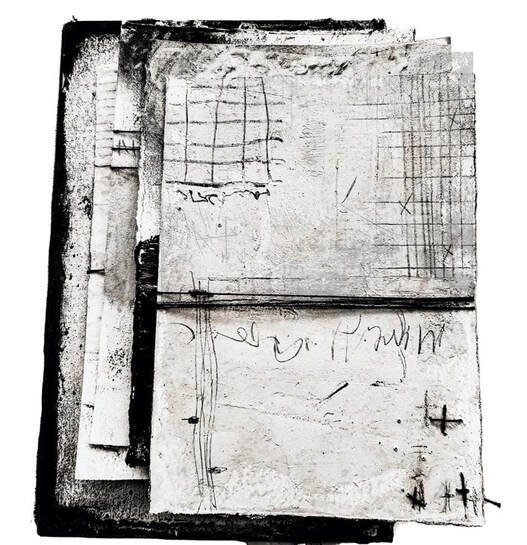

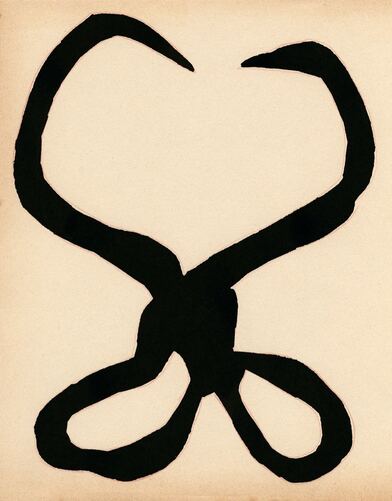

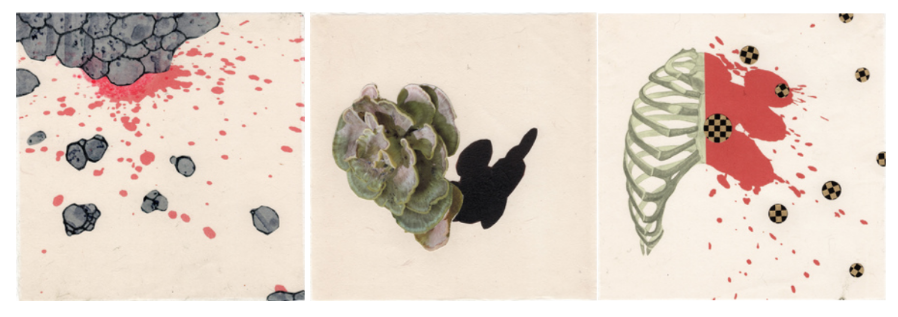

My past contributor, Luisa A. Igloria (the Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia), also started creating three-dimensional art & writing pieces. Now she publishes her crafts. In addition, she is organizing a Poetry Postcard Project this National Poetry Month. I noticed more and more that writers jumped into different genres like paintings, playing music, practicing yoga... and many of them started new professions in addition to their existing writing careers. "At the risk of making a fool of myself..." What kind of risk can I take to further myself? I create graphic poems and play the piano. Why do I -- write in Japanese -- don't I? You may be thinking it is your native language! And you'd be right. But I have never seriously written stories in my mother-tongue. Now, I am writing something in Japanese everyday. This is how we -- writers -- keep building on our craft: at the risk of making fools of ourselves. Essay by Anne McGrath Having been crushed by art teachers early in life, I was as frightened of drawing as I was of taking the math portion of the SATs. Humiliating attempts at making art had revealed my inability to create anything resembling anything I was aiming for. By the age of six I’d written an obituary for artistic endeavors. Then the pandemic lock-down hit and I found myself at home with time and a small tray of my son’s leftover watercolors, crayons, and markers. I started scribbling, collaging, and experimenting with mark making using bright colors and wild lines. At the risk of making a fool of myself I posted one of my creations on Instagram. I connected with other artists and posted another, and another, and I have made and shared some form of art nearly every day for over two years now. I began trying every art form that caught my fancy. I hand-sewed textiles into little booklets made of scrap fabric and left them covered in dirt for months to deconstruct their surfaces. You never know what you’re going to get! I buried the one pictured above in the fall, dug it up in early spring, and washed it in a mudpuddle. It was underground through rain and snow and had delightful little squiggly marks on one page where a leggy bug had roamed through. The process was meditative and joyful, which is how I now think art making should be—full of wonder. My pile of vintage books was perfect for making erasure poems. I was amazed when gorgeous literary journals like Thrush, The Indianapolis Review, The American Journal of Poetry, and The Ilanot Review agreed to publish them. I bought several Pilot Parallel pens and discovered the bliss of asemic writing—placing brush strokes on paper to form words without regard to logical language structure. It was thrilling to let my imagination run free and I had no problem looking beyond the illegibility of my writing to find beauty and inspiration. I was writing nonfiction before the pandemic but stopped to focus on worrying and am only now returning to a semi-regular writing process. My visual art practice—now mostly in black and white— has expanded the way I perceive the world and I’m hoping this shift will inform my writing. It’s easier for me to see value gradations in a limited palette and I want to approach words and sentences in a similar way, to keep things clean, to add wonder and meaning in layers. I’ve learned that using a range of values—light, medium, and dark—makes my visual work more interesting. I can create an energetic mood using strong contrasts or I can create a sense of calm using more subtle variations. I want to bring these nuances and juxtapositions to what I write. Something as simple as using different values in a piece reveals visual texture and a sense of depth which can be used to lead the viewers eye around a canvas or a page of text. Depth and texture might be added to writing by alternating big and small voices and varying the lens from closeup to distanced. If I can pair down my palette and my expectations for my writing, be open to taking to risks as I did with my visual art, I think I’ll find more satisfaction in the process. Anne McGrath was noted in the 2020 Best American Essays series, she was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and she was the recipient of fellowships from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She has work published or forthcoming in Creative Nonfiction, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, Ruminate, Entropy, Columbia Journal, The Writer's Chronicle, and other journals.

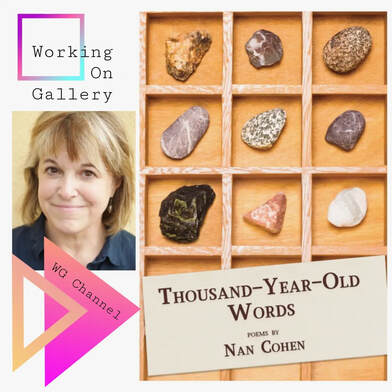

Today's Working On Gallery Instagram guest is Nan Cohen!

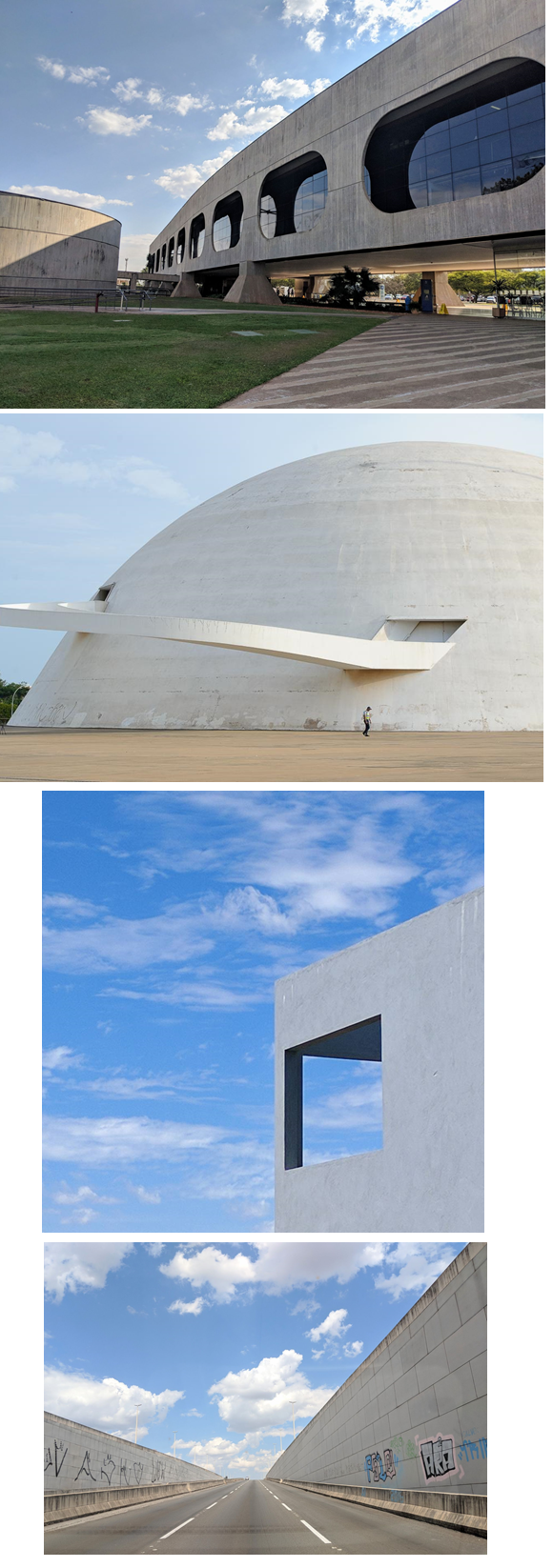

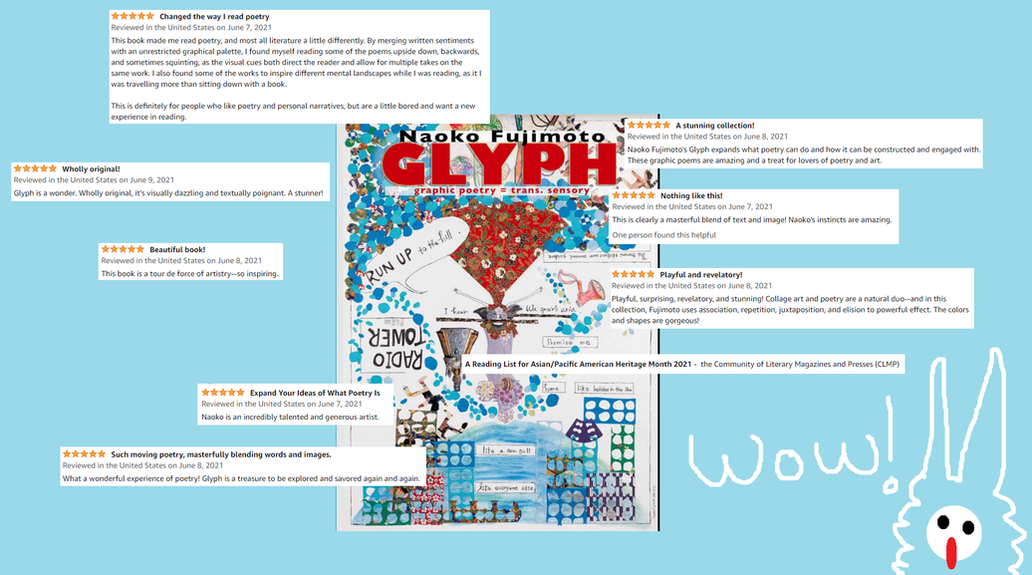

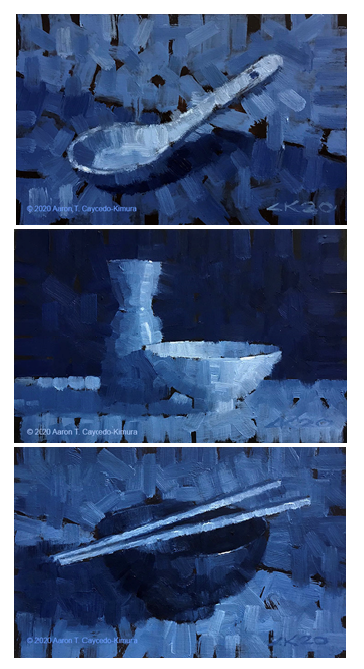

Her newest book, "Thousand-Year-Old Words", has just come out from Glass Lyre Press (Chicago local Publisher). She is currently a resident at the Ragdale Foundation. Please enjoy watching her reading on Instagram WG Channel. First time I saw Francesca Preston's works was when she submitted her piece to RHINO Poetry. She added images to Luisa Caysedo-Kimura's poem, "Santa Rosa 2015" (RHINO Poetry, 2020). Her art was shared in RHINO Poetry Instagram. Later, we exchanged some letters and email, she told me of an article about Anselm Kiefer. I acknowledged him in my book, "GLYPH", because I created my very first graphic poetry sketch in front of his gigantic concrete pieces in North Adams, MA.

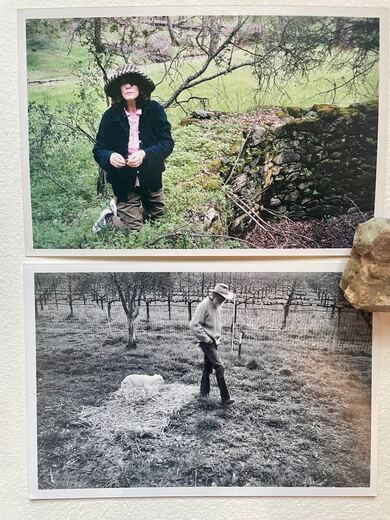

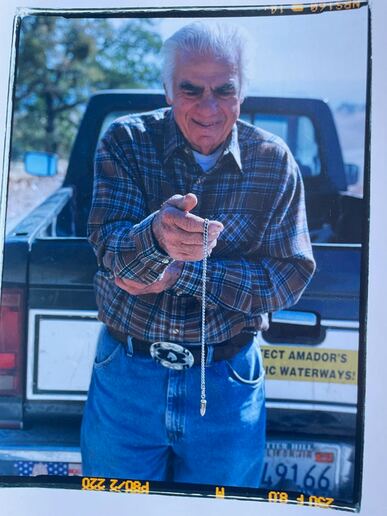

After I read the article (New York Times, Interview by Karl Ove Knausgaard, 2020), Keifer reminded me of Professor Calculus from the Adventures of Tin Tin. Both are genius, but oddly strange -- perhaps, like movements of a pendulum. In case you are unfamiliar with his pendulum, you may visit this Q & A website about How does Professor Calculus's Pendulum work in Tintin? Yes, it is weird. I used a pendulum when I was sixteen in the countryside of Oregon. It was my first summer visiting the United States by myself without any English abilities. I was there as a part of school activities or sort. I knew that it was a pendulum (thanks to Processor Calculus), but I still did not know why a young Japanese girl with no English-speaking abilities ended up walking in circles with a pendulum in the middle of nowhere. Where does this pendulum keep guiding me? From Preston's picture (in the very end of her essay), there is a pendulum with Tony Himan, Water Witcher. I assumed that he used his pendulum to look for signs of water. "The question of whether water witching actually ‘works’ doesn’t interest me. I know it works, in the way that I know poetry works. What does interest me is how a poet, an artist, or a water witcher tunes their body to their craft. Writing a poem, like looking for underground water, is feeling for something you can’t see – a fluid source, a mystery that cannot be truly comprehended. But you can use that source, you can work with it." I wonder if my pendulum experience connected me with today's craft essay. My Language Wants to be Seen By Francesca Preston I once spent time with a talented water witcher, a special man named Tony Himan. He’s gone now. He would be hired to dowse for peoples’ wells - still a common practice in the country. We stood together in the dry, rocky foothills of my grandmother’s land, and he showed me how he looked for water. On the surface it was simple – he was just holding a bit of dangling metal and walking around. Tony Himan was so good that he could tell not only where the water was, but how deep within ten feet, and what minerals were at certain layers: where salt, where iron. He was self-taught, and had spent years practicing in a big cardboard box out in the fields. He said it didn’t really matter what tool you used; in the end it was all about the relationship between your mind and your hand. You have to develop the rest of it. The question of whether water witching actually ‘works’ doesn’t interest me. I know it works, in the way that I know poetry works. What does interest me is how a poet, an artist, or a water witcher tunes their body to their craft. Writing a poem, like looking for underground water, is feeling for something you can’t see – a fluid source, a mystery that cannot be truly comprehended. But you can use that source, you can work with it. The comparison here is perhaps obvious. Word/image = water; writing/making art = tapping, listening, using your body and mind to locate, to place. But Tony Himan revealed something to me that I will never forget. He practiced in a cardboard box! The thought of him carrying an enormous cardboard box out into the fields, and sitting inside it while he concentrated with his mind, re-minds me of my childhood, and my inward-looking self. How the land tugged the fingers of his mind. I grew up in the country on a dead-end road. It was eerily quiet, and we had few neighbors. I spent a lot of time by myself, reading, drawing, and fantasizing about making 3-D houses out of white paper. Every once in a while we’d go to San Francisco and my mother would take my sister and me to an art museum. Eventually I noticed something internal: when I’d look at a piece of art on the wall, I would feel an intense urge to read the title underneath it first, or at the same time. My eyes would flick back and forth, out of my control, and I often couldn’t settle down. But when I looked at pieces where image and word, art and text, were fused – as with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Bruce Nauman – I felt my body relax and a sort of ecstasy emerge. It continues to be this way for me. I have a presiding obsession with the relationship between words and images, and a desire to have them together. More specifically: to rejoin them where they have been broken apart, back to their birthplace in the earth itself. In working on this essay I realized yet again that my art is the pictographic version of my writing: symbols that circle back to what I’m tracking or constructing in the verbal realm. My art is writing too. When I encounter unnecessary jargon in the world – dead, technical language used to alienate people – I get really angry. This type of language refuses to allow images in the mind, which I believe are essential to live. My language wants to be seen. These are old, blacksmithed ice tongs from the ghost town where my mother grew up, and to which my Ligurian ancestors arrived in the 1800s. I have never used them. There is no longer a need to lift heavy blocks of ice – cut from a pond! – in order to keep food cool. But the iron object, which resembles scissors or birth forceps or talking snakes, gnaws on me with its enduring presence. Hefting chunks of a frozen ‘body of water’ in order to keep something (that will be consumed in short order) seems related somehow to the act of writing – from fluid to solid to fluid again. Catching a thought-form in the right state, working with it as fast as you can, and then letting it do its own thing. * During the pandemic I’ve started listening to people more, or rather overhearing them. Perhaps it’s that the opportunities for stranger-exchange are fewer, so I am alert to any stray gems. A couple weeks ago I heard teenagers in a cafe discussing the holidays, what gifts they’d received, and the topic of gift cards. I heard one say, My family’s so weird. I had a massive laugh inside when I heard this. I love that she used such specific words (for a teenager, particularly) to describe what she didn’t want: tangibility, specificity, the physical evidence of choice. And I realize that is exactly what I do want in my writing, and my art. I want to use mysterious means to pull tangible and specific things out of the ground: coins, parts of old tools, bits of dialect, other peoples’ dreams, neglected words, uneasy memories, anything ancient. My poems are often dark-humored. It is no surprise to me that ‘humor’ originally meant ‘bodily fluid.’ The inner syrup of not only humans, but animals and plants, occupies me. No matter what I think I want to write about, there is often my family in the way, like a cow standing in the road on a warm night. By ‘in the way’ I mean part of the way; they are part of my work. By the time I was 10, my mother had fully become a painter, and would leave cryptic notes to herself around the house, things like ‘tiny, squash-eared babies’ or ‘precarious’ written twice. There were always words in her paintings. She walked on them intermittently, and then left them on the floor, where I would come to stare as if they were lost siblings. My father was (is!) a rebellious farmer who started baking bread when I was a child. The images of dough being kneaded and allowed to rest are visceral for me: flour and bread enter my poems regularly, like a kind of ghost. In a recent piece for the Ekphrastic Review I found myself describing my great-great-grandmother’s face: moon-wide as bread / squashed into a suitcase. The polarity of dough-rising (roundly expansive) and the truncated form it must sometimes take (boxy, contained) feels like what her life must have been, in shifting from one place to the next. My desire to retrieve things applies to my poems themselves. I have a chapbook coming out, {If There Are Horns, to be published by Finishing Line Press} after 17 years of not sending out poetry. I wanted to honor these older poems, written as I was navigating within and away from my family, away from academia, away from this country, becoming lost in an important way, and then back finally to the land of my ancestors. I wanted to give them a home, a suitable container, after all these years. Francesca Preston is a writer, artist, and editor based in Petaluma, California. She graduated summa cum laude from Amherst College, and then dropped out of two MFA programs in her twenties. Her poetic works have been published or accepted by journals including Ambidextrous Bloodhound Press, Crab Creek Review, Ekphrastic Review, Fence, Feral, MALUS, Phoebe, Walrus, and her essays by various magazines. The land she mentions in the essay, a ghost town called Calaveritas, is located in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Her chapbook If There Are Horns is forthcoming in fall of 2022.

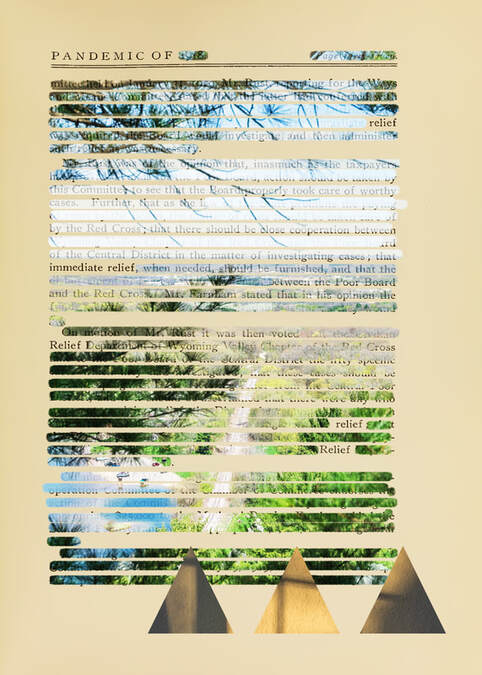

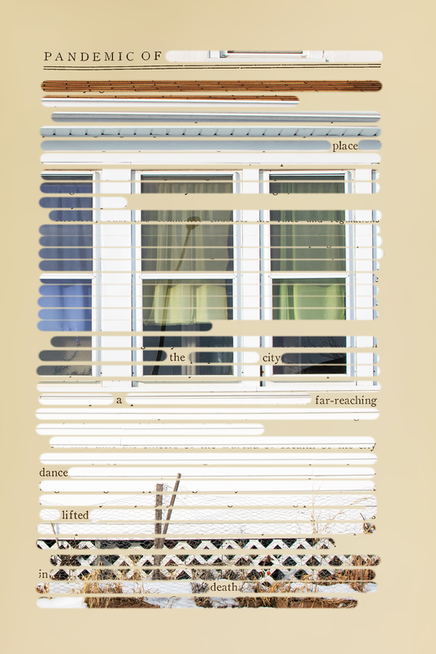

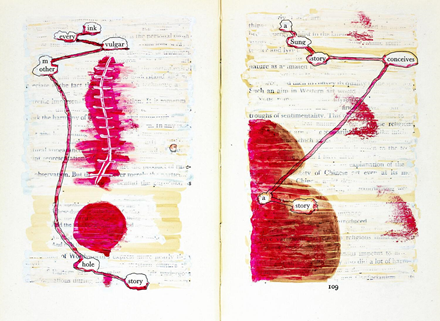

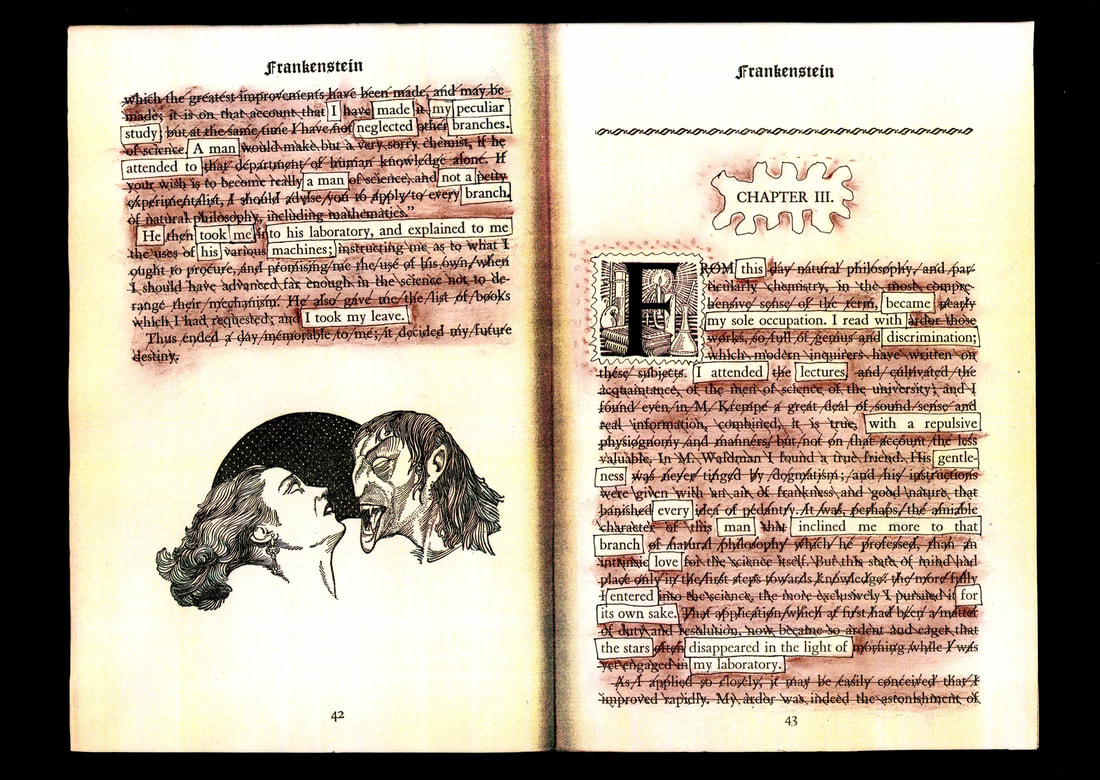

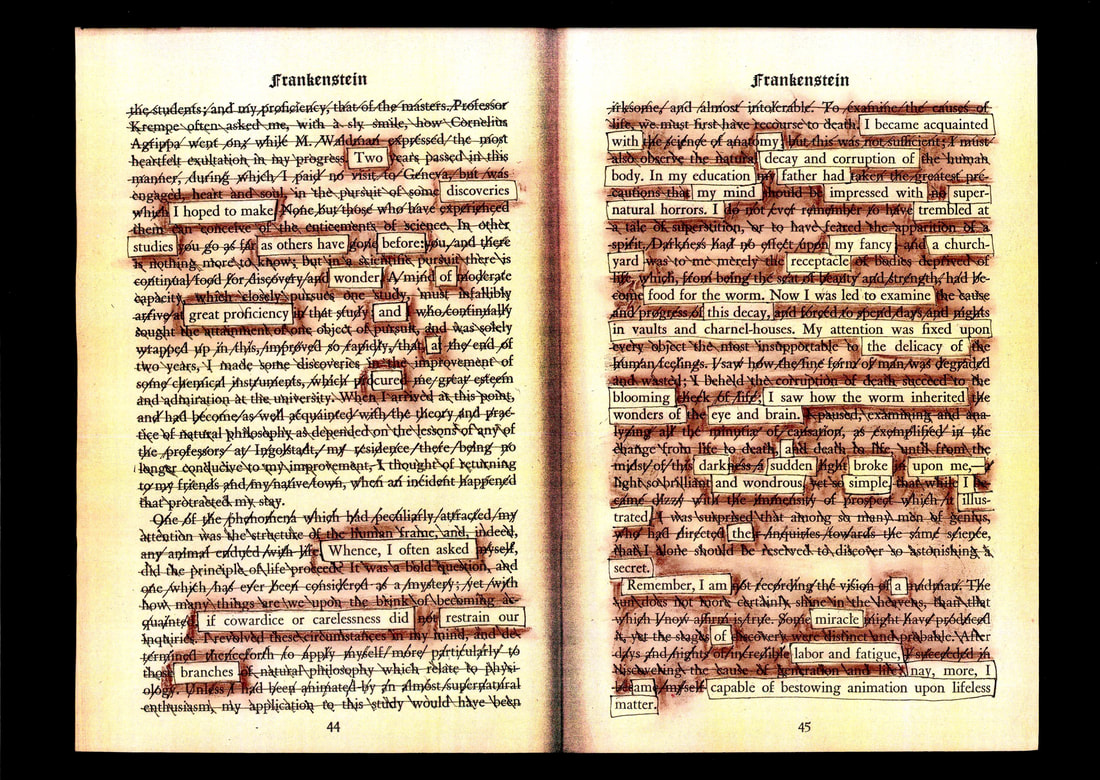

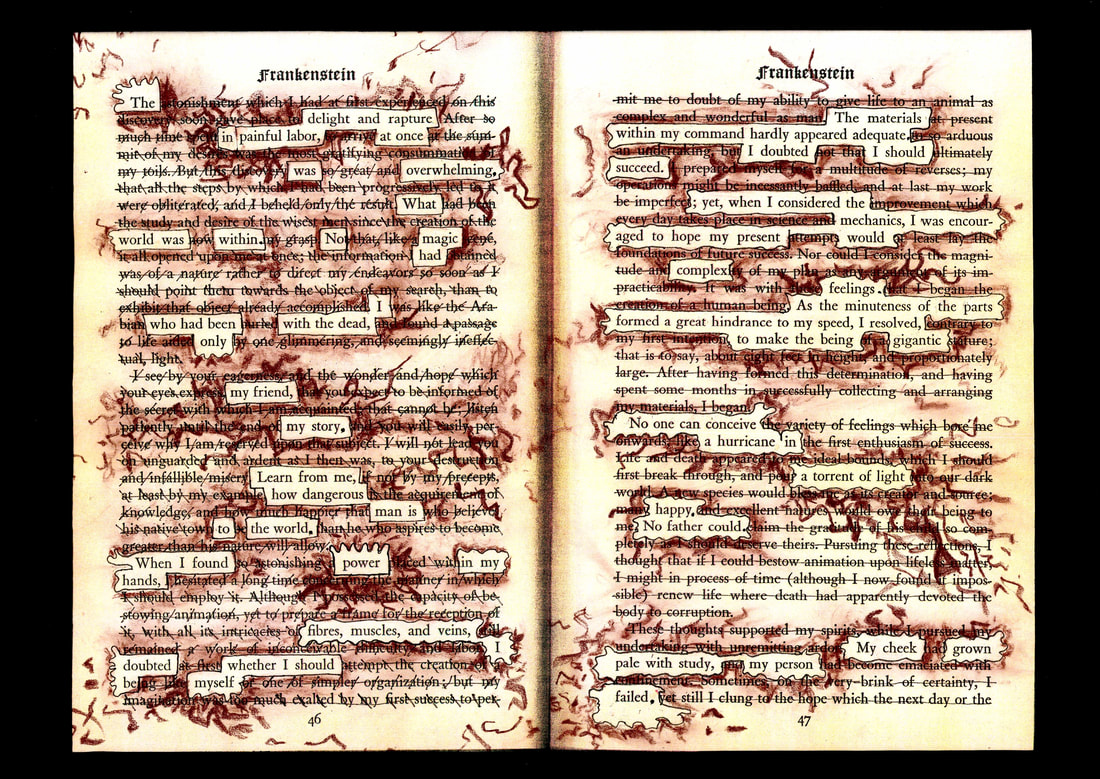

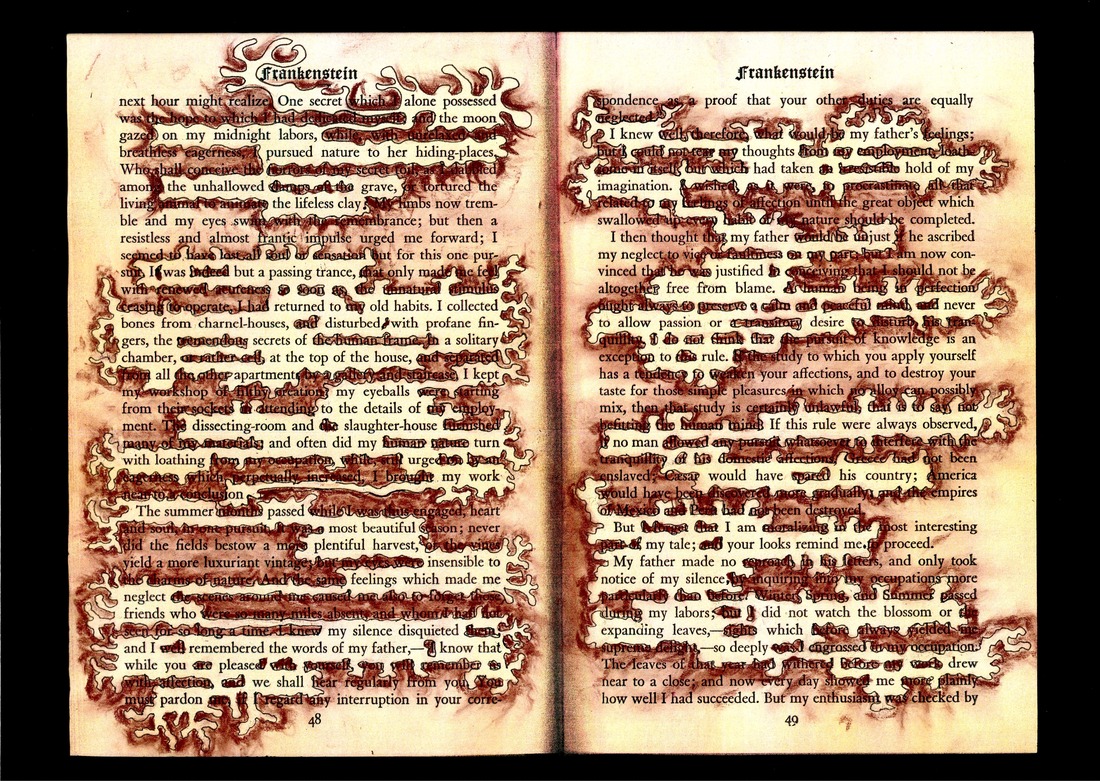

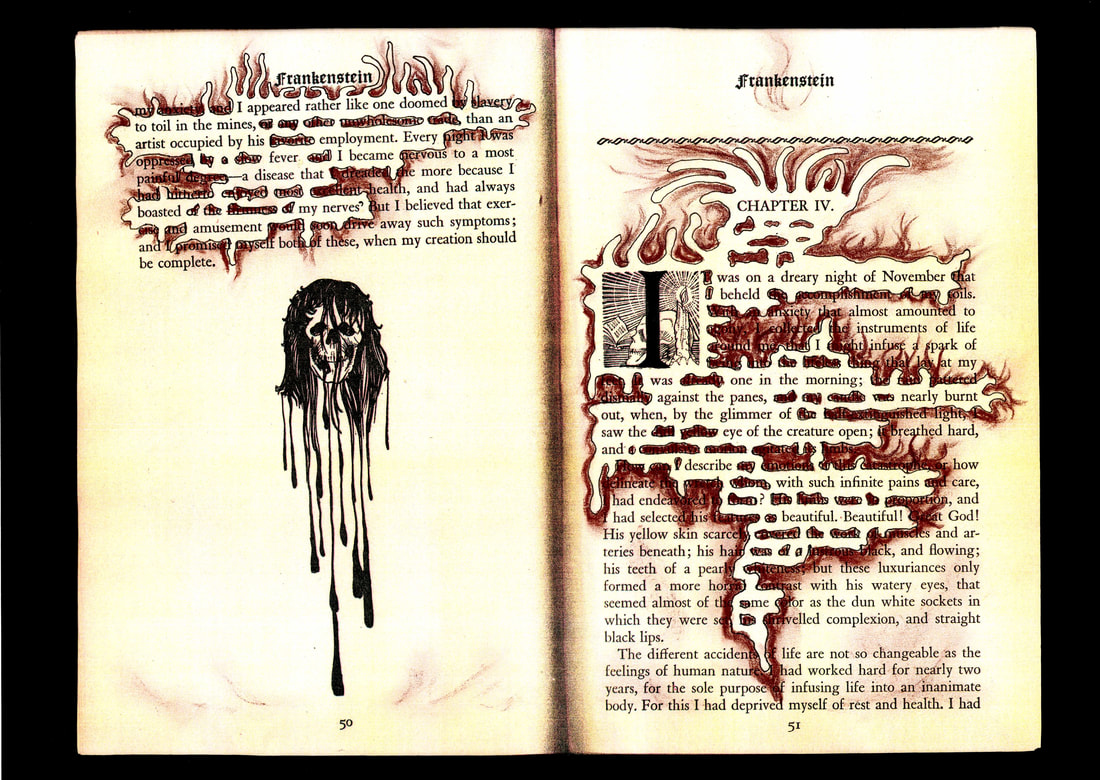

Website: francescapreston.com The first time I saw Kelsey Zimmerman's erasure poems at Indianapolis Review, I immediately contacted my dear friend Natalie Solmer, and I asked her to introduce Zimmerman. I sensed new elements of visual erasure poetry from her work, but I couldn't pinpoint exactly what they were. Her poetry erasure technique is similar to other erasure poets (erasing words from an intriguing original text), but something stood out and captured me. Coincidentally, this was around the same time I was discussing and observing erasure poems with students at Northen Iowa University. I eventually created a study guide for Visual Erasure Poetry, and in it I wrote Zimmerman has advanced versions of visual erasure poems that we were currently familiar with. I was glad that Zimmerman shared her creative process because it identified what I was seeing as new to visual erasure poems. Her work was indeed moving forward based on what we knew about visual poems - - she was inspired by many poets & artists such as Douglas Kearney, and then she created her erasure poems using new computer tools and existing photos that she took. Now, I understand how her vivid colors (she uses monotones, but those colors stand out) were adapted, and how she thoughtfully coordinated texts & images. There are new elements that uniquely signify her work. This is both unexpected and thrilling, and I seriously enjoy being in the front row of this visual poetry renaissance. YouTube by Douglas Kearney, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Octavio Quintanilla and Jennifer Sperry Steinorth. By Kelsey Zimmerman In March 2021, I attended an AWP session online that pushed me for the first time towards visual poetry. Compounding the Line: Visual Poetics in a Word Doc World with Douglas Kearney, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Octavio Quintanilla and Jennifer Sperry Steinorth. For some time, I’d been thinking about ways to integrate the photos I take with poetry and hadn’t been able to identify a method that didn’t feel tacky somehow—my worst fear was creating something that made someone think, “Looks like that was done in Canva!” But the examples of these amazing artists in this session reinvigorated this quest for me. Douglas Kearney shared a video of some of his process while working with Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator that, in particular, opened my eyes to the possibilities there if I could improve my comfort with the software – I was a novice, but already comfortable with Adobe Lightroom Classic and InDesign. The cross-platform functionality of all Adobe programs is somewhat similar, and my knowledge of the latter provided a much-needed entry point. Around that time in March, I was also in a poetry workshop in my MFA program that centered on the performance of poetry, not just as it’s spoken aloud, but how it performs on the page. I began to integrate that idea into my “normal” poetry, but also began to spend much more time thinking about how visual elements could perform on the page and what exactly I wanted any visual poetry of mine to say. I also read Hotel Almighty by Sarah J. Sloat, which proved highly influential, and a friend introduced me to Nets by Jen Bervin, Emily Dickinson’s postcard poems, and several other books on the history of concrete and visual poetry, and explored the work of several small presses, Ugly Duckling Presse in particular (and UDP is now very high on my list of dream publishers, given the esteem in which I hold their work!). Another friend had worked with Katy Didden at Ball State as an undergraduate, and her Ore Choir was another inspiration. Trying to situate myself into the context of the arena I hoped to enter was both daunting and inspiring: there was my little myopic self, surprised on some level that so many other people had worked to solve this same problem, make art in this same vein. All their work proved to be instructive and inspirational. I often think of my creative process as a sort of machine, or maybe an animal, where I go through weeks or months of input input input input, voraciously reading and exposing myself to ideas, and at certain points I sit down and switch to output. So I had all these things floating through my brain and had some half-formed ideas floating around, and there was one thing on my brain that superseded most other thoughts, and those were thoughts on the pandemic. The idea for how I would make an erasure poem of poetry had come to me, but I had to have the right text and the right images. Luckily, I already had a catalog of thousands of my own photographs to choose from. But for those initial text scans, I turned to archive.org and searched “pandemic.” That’s how I found the text for these works in The Indianapolis Review. A small tome, digitized in the infernal magic of the internet, on the 1918 flu response and vaccination, in the public domain on the Internet Archive. As far as page selection goes, I choose the ones I make erasures from more or less at random: I do scan the page for content, looking for words I think I can work from, words that interest me and spark something – I also especially like pages with ornamental designs (such as chapter openings in some books) and lots of white space (such as on chapter-ending pages). These allow for an extra dimensionality, another way of letting the original work speak for itself and highlighting what it says in a new way. The examples of my work in The Indianapolis Review are from the very first time I sat down to ever seriously try to create something like this. It’s fascinating to look back because, while I still like them, there are definitely things I’d do differently now – especially when it comes to figuring out ways to make the text flow more easily and stand out -- though in these pieces that the text and imagery battle for first relevance is a feature, not a bug. There are thousands of photographs in my catalog, and after skimming a page I’d picked to be an erasure, I comb through all those photos for one that seems like it would capture the right mood. From there, it’s all listening to the combination of words and image within the project, letting the final form reveal itself. Since March I’ve found it’s extremely difficult to find high-quality scans online, even on websites like archive.org or Project Gutenburg. Or if you can find them, they sometimes have restrictions associated with the file types or the scan quality as low. I take my own scans now, with books of my own or interesting ones I find at estate sales or thrift stores. In the meantime, I’m continuing to make more erasures in this vein, but am also always trying to think of what to do next. There’s always some boundary to be broken. Kelsey Zimmerman is a writer and visual artist from Michigan currently living in Iowa. A 2021 Best of the Net nominee, her work is published or forthcoming in Hobart, The Indianapolis Review, Nurture: A Literary Journal, and Ghost City Review. You can find her on the web at www.kelseyzimmerman.com or on Twitter @kelseypz.

It was an interesting coincidence that Leão talks about Yukio Ninagawa, a Japanese theater & movie director, in her essay.

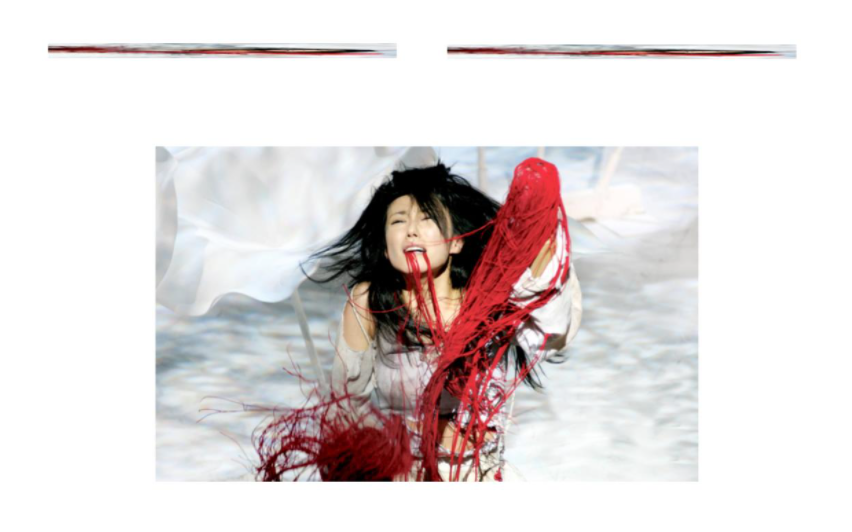

Recently, one of Ninagawa's productions had its final show. He created Saitama Gold Theater with only actors who were over fifty-five years old. Due to the pandemic and declining number of performers over recent years, the company officially closed. Ninagawa is best known for adapting Shakespear plays into Japanese and fusion cultures. Here is one example on YouTube of his production of Hamlet. There are translations in Chinese and English; however, the actors perform in Japanese. Their stage sets and costumes are deeply influenced by Japanese traditions.

The majority of Japanese people were not familiar with Shakespear until Tsubouchi Shōyō translated all the collections from 1909 - 1930. Some of his translations have free online archives available at Aozora Bunko. So in Japan, Shakespear is considered "new" reading. Many people do not have the opportunity to read Shakespear in its original English, but they seek life answers from translations. I also did not know that Tsubouchi spent his childhood in Nagoya, my home city. (Borrowing Leão's words, I had never researched - - until now.) In addition, he was one of the first to highlight the differences between European and Japanese writing styles. He explained European key writers such as Homer and Dante. Tsubouchi also wrote a textbook of English Literature 101 contrasted with Japanese writing history. "I had never researched - - until now..." This is what I want to achieve with Working on Gallery. A curious dot guides the us to unknown, large reflections. I met Lúcia Leão in Miami when SWWIM hosted their monthly poetry reading event at the Betsy. She helped me order a magically tiny emerald-like key-lime pie and a small porcelain cup of coffee in Little Havana. I indeed felt like Alice in Wonderland. There, people often speak both Spanish and English, switching flawlessly between each. I witnessed how Leão's writing reflects this fusion culture. This w-place By Lúcia Leão I often feel that writing poems takes me to the theatre. The morning I was imagining this piece, one image caught me. It had been laying on top of a chest of drawers in my bedroom for years. It would not leave me. My eyes traveling around it, thinking − Graphic? Appealing? Flowing red strips made of silk, so scarlet I had to look for wounds. It seemed it was not by chance that the mouth and the hands exposed the hurt. Places of words and writing. Eyes facing grief. Trying – able? – to stay with the movements of meanings. The photo is on the cover of a book. It is from a Japanese production of Titus Andronicus, by William Shakespeare. Directed by Yukio Ninagawa, designed by Tsukasa Nagagoshi, Royal Shakespeare Company, 2006. This is Titu’s daughter, Lavinia. She suffered a kind of violence we can and cannot absorb from this picture. Blood has been replaced by silk, to soften the horror, to increase it. My mind recalls Artaud and traps me there. Where to go with this? The page as the stage. A flow of words being held and escaping. A corridor opening to many. I am still looking at the picture, my eyes in a curious fashion, with hers. There is no tongue. There are no fingers. I am an explorer. It is a tragedy. And this, not an exit sign: A name under Shakespeare not familiar to me. But of course, the photographer is Brazilian. My roots not a point of departure but of a meeting. She lives in London, not in Brazil. The traveling eyes and the traveling mind continue. It was in a bookstore in Rio de Janeiro that a friend and I got together, both by then foreigners in our city of origin, drunk on the joy an antique friendship releases. About to leave, she bought me the book, gift-wrapped it. The cover a postcard I kept of a time, of the craft of theater. I had never researched the photographer or the stage designer, until now. London, Rio, Japan, the places where I am – restart and mix. Pain, cruelty, hatred, and love – subtitles that move. They walk on the surface where the names stay. This is more than a postcard. But the leap to graphic poetry seems to be missing. In the play, Lavinia is able to grab a staff, put it in her mouth, and write on the sand the names of the people who had harmed her. There is a deeper wound the photo doesn’t show. While approaching this frame, I was drawing myself close in the process of her, sentences brushing against sensations, opening air. Papery silky strips in this w-place. The leap missing. But first we circle, select, gather, leave behind pieces. Lúcia Leão is a translator and a writer originally from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Her

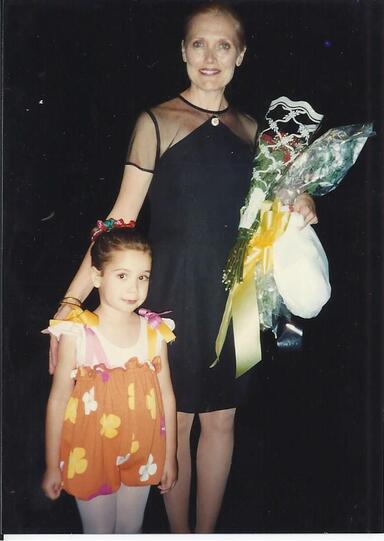

poems have been published in South Florida Poetry Journal, SWWIM, Gyroscope Review, Chariton Review, Harvard Review Online, among others. Her work is included in the anthology Grabbed: Poets and Writers on Sexual Assault, Empowerment & Healing, edited by Richard Blanco, Caridad Moro, Nikki Moustaki and Elisa Albo. Lúcia has been living in Florida for twenty-five years. I met Claire Bauman at Enrich Chicago workshops, where we learned how to update ourselves for an anti-racism initiative in Chicago art professions. We had the opportunity to learn about each other (she knits for her family members!) and I was interested in knowing more about her theatre directing along with her ballet and dancing experiences. "Just technique is stiff and academic. Expression alone is chaotic. But, together, they are exquisite." Bauman compares her art theory with "form" and "structure". I think that if dancing is cooking, "form" is the ingredients (pumpkin, flour, & spices...) and "structure" is the recipe. What can we cook with pumpkins, flour, & spices? Pumpkin pie? Or Pumpkin tempura? With the same ingredients, the outcomes can vary depending on how we approach them. The performer takes their ingredients (emotions, academia, & experience), and uses them in a performance flavored with the nuances of how each were prepared. The outcome becomes a tragedy or comedy. Her conversation reminded me of my recent Instagram TV guest, Jen Karetnick, who said, "Everyone gets the same ingredients & recipes, but the cook must tweak it for the best taste. It is same as writing poetry". "It may be easy to write off an arm gesture as icing on the cake, but I see such movement as an inextricable aspect of choreography that transforms simple dance steps into a form that can be manipulated to carry meaning." Bauman is my first guest outside the writing community. But I love to realize again how art and creativity connect different professions. PERSONAL MUSINGS ON FORM AND STRUCTURE By Claire Bauman (she/her/hers) Every ballet class begins with pliés. As the knees bend to a demi plié, the arms float to first position, and the head tilts, gazing at the palm. As the knees extend, arms open to second position, and the head follows the hand out. This exercise not only begins class, but also forms the foundation of most balletic movement. But it is not just the mechanics of the movement that matter. The épaulment, or positioning of the shoulders, head, and neck, and the quality of the movement are essential in creating subtle, twisting lines, a sense of effortlessness and grace, and depth of emotion in any movement. Moments like the Black Swan’s 36 fouettes are easily memorable and spectacular even, but what is Swan Lake without the iconic floating, beating arms of the swan corps de ballet? It may be easy to write off an arm gesture as icing on the cake, but I see such movement as an inextricable aspect of choreography that transforms simple dance steps into a form that can be manipulated to carry meaning. My interest in theatre began with ballet. The story goes that I begged my mom to allow me to take extra ballet classes in preparation for the annual exam required to pass on to the next level of training when I was in kindergarten. Throughout my childhood, my teachers taught me to point my feet properly through reminders to avoid “dead fish,” to expand and lift through my chest by feeling the sun shining onto it, and to elongate through my neck by imagining myself wearing a crown. This imagery allowed me to tap into the creative and emotional qualities of ballet. I didn’t have the highest grand battements or the most pirouettes, but I stuck with ballet for as long as I did because the rigor of the technique gave me an emotional outlet to explore storytelling. I loved both the technique and the expression because they needed each other to be a complete artistic form. Just technique is stiff and academic. Expression alone is chaotic. But, together, they are exquisite. I would not work the way I do as a theatre maker if not for ballet. Whether I am directing, devising, or choreographing, I seek to create meaning through form: the shape, appearance, or quality of something. I build images, metaphor, and juxtaposition to construct meaning and evoke visceral responses in audiences. If form is the essential construction of an entity, I believe those inherent qualities can elicit emotion. Let’s return to the ballet. Throughout Act II of Giselle, it’s a common stylistic, or formal choice, that Giselle and the Willis (maidens who have died before their wedding day) dance with their eyes downcast. The eyes downcast is part of the form of the steps for these characters, creating an eerie aura of grief. The Willis would not be half as powerful without this choice. I do not think form is synonymous with structure (the organization of things). But structure is an important component in creating meaning, and another study ingrained this perspective in me. I chose to take Latin in high school (following after my brother). I loved it because it also uses form and structure to create meaning; in this case, through cases (pardon the pun). Cases are like verb conjugations but for nouns and adjectives. Latin uses cases because it does not require word order. So the ending of the word tied it to other words rather than its location in a sentence. And by changing the case, you change the form, and therefore, the meaning of the word. With a different case, the word “painting” becomes “to the painting” or “of the painting.” Words and their cases could have their meaning further manipulated through rhetorical devices. This leads us from form to structure, from the manipulation of the thing itself (words, in this example) to the manipulation of their organization. Rhetorical devices are the structures that elevate language into poetry, layering a visual and auditory meaning onto the simple definitions of the words. Alliteration is a good example, since we also use it in English, and such repetition of consonant sounds can add to an emotional response. Because of the use of cases and the fluidity with which words could be placed in a sentence, Latin gave us other devices like chiasmus, a mirroring device that placed words in an “a b b a” pattern. Another favorite is caesura, a word break in a phrase. This makes Latin poetry even more powerful through its visual structure. I fixate on form and structure in theatre because I think they are often overlooked as the containers of meaning which can evoke emotion in an audience. And form and structure are a choice. Choice is where my artist perspective and inquiry emerge from. So often, in art and society, we forget that everything is constructed, and anything that is built can be built anew through different choices. Antonin Artaud hones in on the power of theatre to challenge social inequity in his essays collected in Theatre and Its Double. He laments that, “our theatre never goes so far as to ask whether this social and moral system might not by chance be iniquitous.” I want theatre to be more than just a story that happens onstage. Form can evoke a reaction more powerful and subliminal within an audience than the combined definitions of words spoken by a character that feels relatable. I hope such an emotional connection can challenge how people view themselves in space and in society. I deeply believe that movement, form, and structure hold the power to change systems and people and that theatre is an essential tool in imagining and creating such change. Claire Bauman a director and choreographer who creates theatre, dance theatre, and performance art through devising practices and ensemble-based collaboration. She approaches her self-produced and devised work with an interdisciplinary and feminist lense. She has worked with Red Tape Theatre, Interrobang Theatre Project, Walkabout Theater, Rhinofest, Broken Nose Collective, and Chicago Theatre Marathon. She is the Grants Manager and an ensemble member with Red Tape Theatre and an Institutional Giving Consultant with Artistic Fundraising Group. Claire has participated in DirectorsLabChicago, Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation Observership Program, and Hangar Theatre's Directing Apprenticeship. She graduated from Vassar College and further trained at the Moscow Art Theater School. You may also like...To read the full essay, click on the picture. We think what we can't see can't hurt us. I met Ann Hudson when I joined RHINO Poetry in 2016. She pays meticulous attention to everything; especially to identify side-stories in our submission reading process. In other words, our editors are often convinced to reconsider poems nearly rejected after hearing her unique interpretation of them.

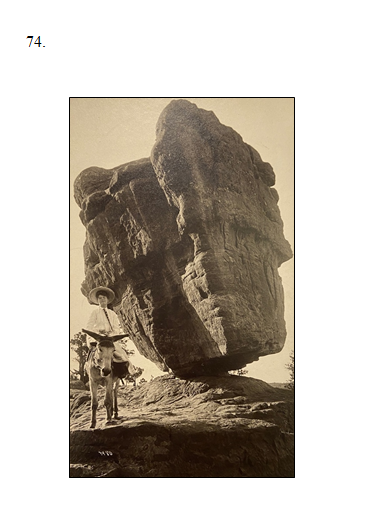

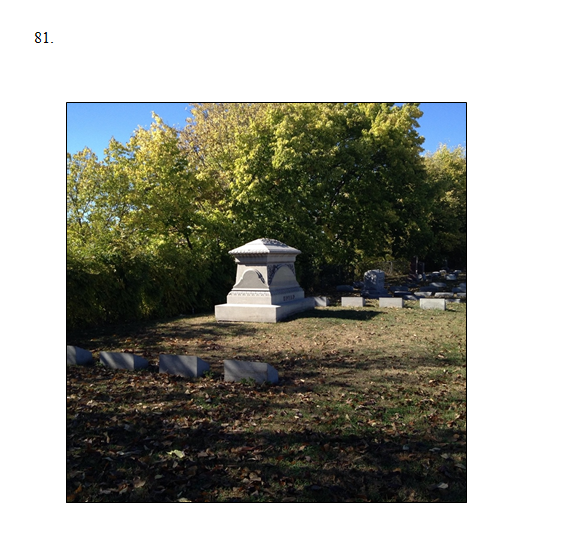

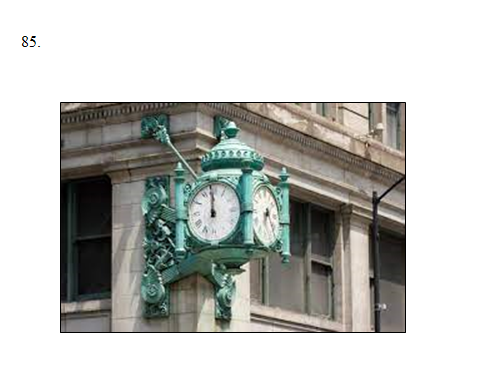

Her new book, "Glow" (Next Page, 2021) has just released. The opening reading event will be hosted by the press on October 26. This collection entangles her family, Marie Curie's discovery, and girls in the Radium Dial Company. The narrative bounces between science and history. The Radium Dial Company opened a factory in Ottawa, Illinois in 1922 to be close to Westclox, major clock manufacturing company in the area. Radium Dial hired young women to paint watch faces with luminescent paint; they were ideally suited for this work, it was believed, because of their fine motor skills and attention to details. They were explicitly taught to press the paintbrush between their lips to get the brush tip to the finest point possible. In doing so, they ingested radioactive paint, which managers assured them was safe This book is one only Ann Hudson can pull off. The language is beautifully tragic. Today, Hudson shares her zuihitsu-like-list essay (her essay reminds me of Sei Shōnagon's "Hateful Things") showcasing the story behind her new book, "GLOW". Ann Hudson, Glow 88 Pretty Much True Facts

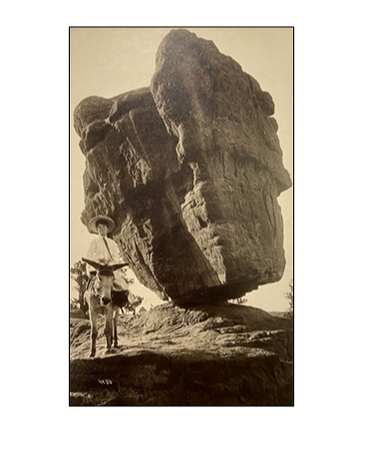

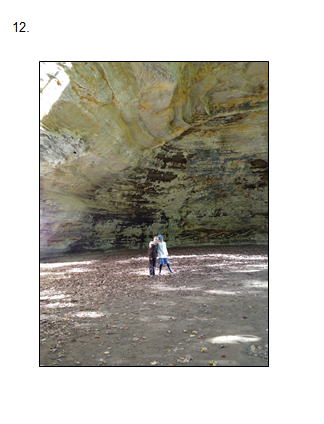

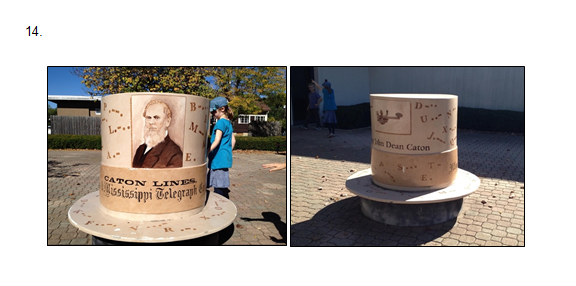

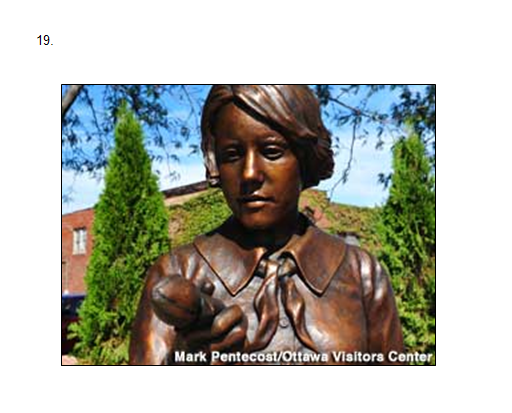

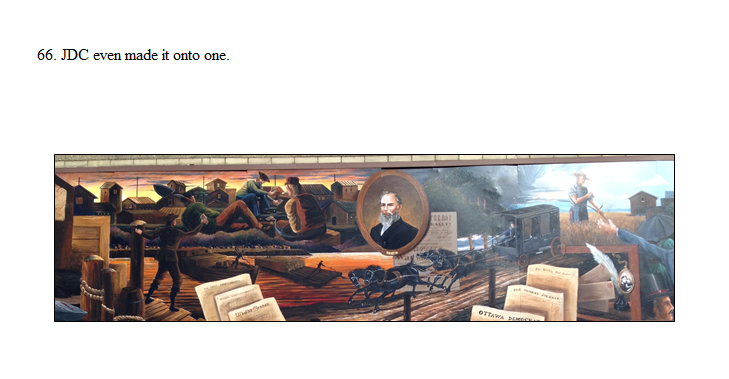

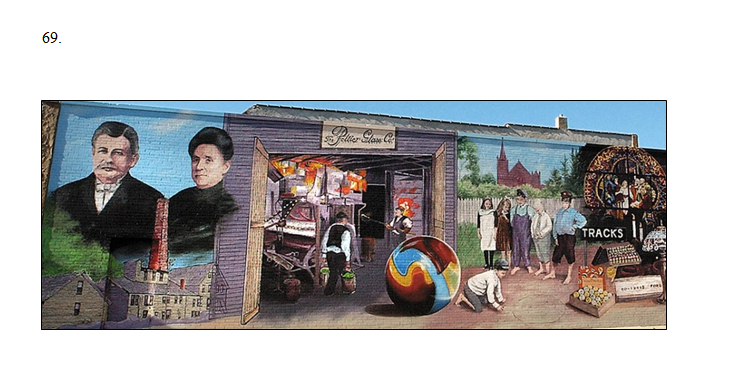

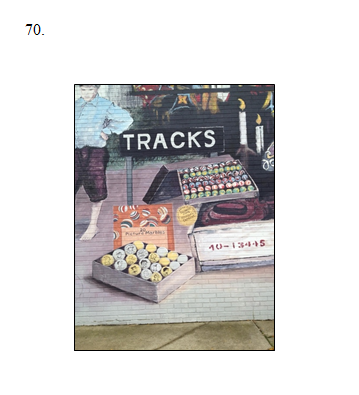

9. John Dean Caton, exhausted by overwork, moved from Chicago to Ottawa in 1838. He farmed for a few years before returning to the law. 10. In 1849 he helped establish the Illinois and Mississippi Telegraph Company, and 18 years later, sold to Western Union. 11. We spent a weekend at Starved Rock State Park, just outside Ottawa. My favorite spot is Council Overhang. 13. One afternoon we visited the nearby Ottawa Scouting and Historical Museum, where Mollie Perrot, local historian and JDC enthusiast, agreed to meet with me. She was excited to meet a Caton descendant. I was excited to see his giant, honorary hat outside the museum. 15. The kids were restless. On our way to get ice cream, we found the statue to the Radium Girls. I’d known it was nearby, but wasn’t looking closely for it. 17. It’s an odd, sad statue. The “girl” in question was likely in her late teens or early 20s, though there’s something about this statue that makes her look considerably younger. 18. The tulip in her right hand sags: defeated, deflated. It’s flaccid. It’s uncomfortable, no matter how you think about it. 20. By the time I got home to Chicago, I was more curious about the Radium Girls than JDC. I didn’t have any intention of writing poems about them. 21. I think “Work (1922)” and “Work (1923)” were the first poems I drafted, intending to leave it at that. 22. 88 is the atomic number of radium. 23. Marie Curie discovered radium. 24. Which makes it sound like she was digging through an attic and found it in an old box. Or she dug it up like a fossil. 25. No. She guessed it was there. She worked in foul conditions, laboring with the heavy materials, tending to a cauldron of what I imagine to be foul-smelling pitchblende she’d somehow finagled to be shipped to her from what is now the Czech Republic. 26. Pierre was interested and supportive. Marie did most of the heavy lifting. 27. At the time she didn’t get her share of the credit. 28. That’s my grandfather’s watch on the floor. It tells time, but it doesn’t glow. 30. My grandfather was JDC’s great-great-nephew. JDC died in 1885, 24 years before my grandfather was born. 31. There are a zillion Johns, Charleses, and Williams on that side of the family. It makes research confusing. 32. Maybe you’re still thinking of that limp tulip. 33. It’s odd to think we vacationed in an EPA Superfund site. 34. The Cleanups in My Community map is pretty sobering. 35. Marie Curie’s cookbooks are kept in a lead-lined vault. If you want to visit them you have to sign a release form. 36. Loie Fuller’s birth name was Mary-Louise Fuller. She was born in what is now Hinsdale, a western suburb of Chicago. 37. I haven’t found Fuller’s Radium Dance on film, but you can see her Serpentine Dance and get a feel for what she was up to. 38. It makes me think of ribbon gymnastics. 39. Fiesta dishware had uranium in its glaze; red was the most radioactive. 40. Fiestaware remains highly collectible. 41. There were casinos where you could play roulette in the dark. The ball and roulette wheel were painted with radium. 42. A musical number called “The Radium Dance” was written for a Broadway musical called Piff, Paff, Pouf, which is pretty mystifying in its own right. 43. One brand name for luminescent paint was Undark. 44. The Radium Girls weren’t just in Ottawa, IL; there were other factories in New Jersey and Connecticut. 45. One bite from a radioactive spider changed Peter Parker forever. But no bad side effects, not even a headache, and he gets the girl. 46. Necrosis: the death of all or most of the cells in an organ or tissue due to disease, injury, or failure of the blood supply. From Greek nekros = corpse. 47. Body burden: the concentration of chemical in the body at any given time. 48. Until the 1970s shoe stores would x-ray your feet to ensure a proper fitting shoe. 49. In 1998 the US FDA declared Mercurochrome as unsafe. 50. Marie Curie’s niece, Helena, was known as Hela. She died by her own hand in Chicago in 1921 at the age of 29. 51. Curiously, scientists refer to the oldest and most commonly used human cell line as HeLa, after Henrietta Lacks, from whom the cells were stolen. 52. A 1933 article in the American Journal of Public Health opens with the paragraph: “The excitement caused by the poisoning, or alleged poisoning, of a number of women engaged in applying a radium compound to watch hands and dials is well remembered. We understand the company was very liberal to the victims, and that new methods have been insisted upon which obviate the danger.”[i] [i]“RADIUM POISONING”, American Journal of Public Health 23, no. 4 (April 1, 1933): pp. 350-351. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.23.4.350 53. After the Radium Dial factory closed down, it reopened a few blocks away under a new name: Luminous Processes. 54. Luminous Processes. Shining Procedures. Glowing Practice. Shimmering Exercise. Radiant Problem. 55. Marie Curie also discovered polonium, which she named after her country of origin, Poland. 56. Peg Looney started working at Radium Dial when she was 17. She made good money: $17.50 a week. She died on August 14, 1929, at the age of 24. The causes of death listed on her death certificate were diphtheria and anemia. 57. Radium can also be instrumental in treating certain cancers. 58. Dial painters were paid eight cents per dial. The faster they painted, the more money they made. They were taught to pinch the tip of their camel-hair brushes between their lips to create a fine point. 59. Chemists at the factory operated behind lead screens. They used tongs. They wore masks. 60. Starved Rock State Park is on land once inhabited by Hopewellian, Woodland, and Mississippian tribes. From the 1500s to the 1700s, it was the land of the Illiniwek. 61. According to legend, Chief Pontiac of the Ottawa tribe was killed by an Illiniwek warrior during a tribal council. During a battle to avenge his killing, the Illiniwek wound up trapped on a cliff overlooking the Illinois River. The Ottawa and Potawatomi surrounded the bluff, but the Illiniwek refused to leave, and many starved to death, giving the area its name. 62. There’s no evidence that suggests this story is true, but it’s so widely disseminated most people take it to be true. 63. John Dean Caton recounted the story during an address to the Chicago Historical Society on December 13, 1870. 64. JDC also turned his attention to studying the natural world. He sent Charles Darwin a copy of a book he wrote on antelope and deer; Darwin sent a gracious thanks, and artfully avoids mentioning whether he plans to read the book. 65. Ottawa has a lot of large, vibrant murals that celebrate its history. 67. The high-quality silica sand in Ottawa is mined to make glass. One newspaper article called it “hypermining.” Turns out it’s not just good for glass; hydrofracking operations use this high-end sand to “prop open cracks in deep underground shale deposits, allowing natural gas to flow freely toward the surface.” [i]The sand is rare, and plentiful in the region. Intense sand mining is putting the local ecology in danger. [i] Dan Ferber, “Scenic state park at center of Illinois frac sand fight,” Midwest Energy News, 6/4/12, https://energynews.us/2012/06/04/state-park-at-center-of-illinois-frac-sand-figh/ 68. The Peltier Glass Company in Ottawa used to produce marbles. 71. William Penn Caton married Elizabeth Steele. They had six children (one John, one William, one Charles, by the way.) 72. Charles Caton married Fannie Hull. They had seven children (including a William and a Charles.) 73. THAT William Caton married Glenore Dallenbach. Here’s a photo of her at age 19, beside the Balanced Rock in Colorado. The photo is dated 1904. 75. She lived to be 100 years old. 76. Glenore had a life-sized doll at the top of her stairs. It scared me and I ran past it. 77. Glenore was my great-grandmother. 78. Glenore’s husband (William, of course) disappeared in 1912. He boarded a train to work and was never heard from again. 79. There’s a glass blowing shop in Ottawa where you can get your loved one’s cremation ashes turned into a paperweight. 80. JDC is buried in the same Ottawa cemetery as William Dickson Boyce, who founded the Boy Scouts in 1910. With the exception of Mollie Perrot, folks in Ottawa seem much more interested in Boyce than JDC. 82. When he lived in Chicago, JDC had a big house on Calumet Ave. Family rumor had it that there was a tunnel of some sort that led from his house to another house. 83. I looked it up in the Chicago History Museum archives. Turns out JDC’s son, Arthur J Caton, was married to Delia Spencer. After Arthur Caton died, suddenly and unexpectedly, Delia married her neighbor Marshall Field, founder of the famous store that bears his name. The tunnel rumor made it to print, with the implication that Delia and Marshall were using it to tryst. 84. So that clock on the corner of State and Washington is in my family. Pretty much. Actually, there are two clocks: one at the SW corner of the building and one at the NW corner. 86. Marshall Fields went bankrupt years and years ago. Its flagship store is now owned by Macy’s. 87. But the clocks are still there. 88. And they still tell the time. Ann Hudson (she/her) is the author of The Armillary Sphere (Ohio University Press); a chapbook about radium, Glow, has just been released from Next Page Press. Her poems have appeared in Cider Press Review, Orion, Crab Orchard Review, Colorado Review, North American Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, and elsewhere. She is a senior editor for RHINO, and teaches at a Montessori school in Evanston, Illinois.

Miami-based poet and writer Jen Karetnick is the author/co-author of 20 books, including the cookbooks Mango and Ice Cube Tray Recipes. Her food, health, and lifestyle pieces appear recently in Allrecipes.com, Business Insider/Insider, The Counter, Indulge Magazine, NPR, Shondaland, and elsewhere. See jkaretnick.com for more or find her on Instagram @JenKaretnick and Twitter @Kavetchnik.

"How do we articulate these feelings and this new way of experiencing the world so that we can communicate it?" When I read Tanja Softić's essay, I realized that my experience being a foreigner in the U.S. may actually be beneficial for the first time. That was really surprising when I thought about it. Often people talk about the disadvantages of being an Asian women or immigrant in the U.S.

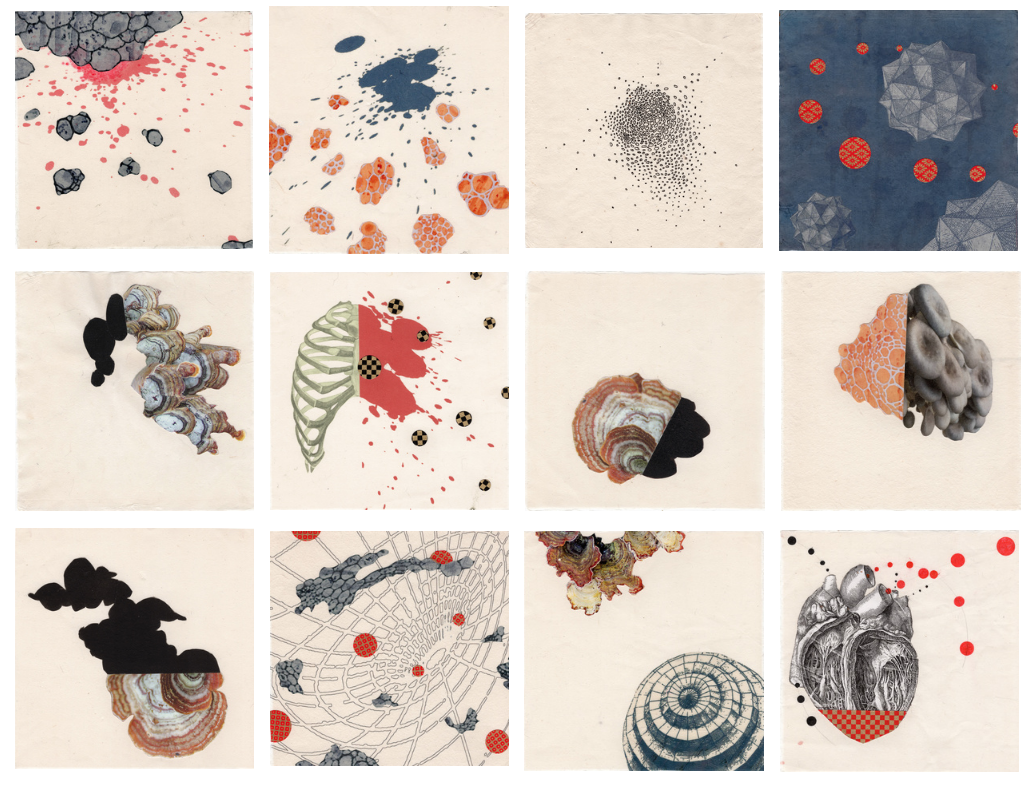

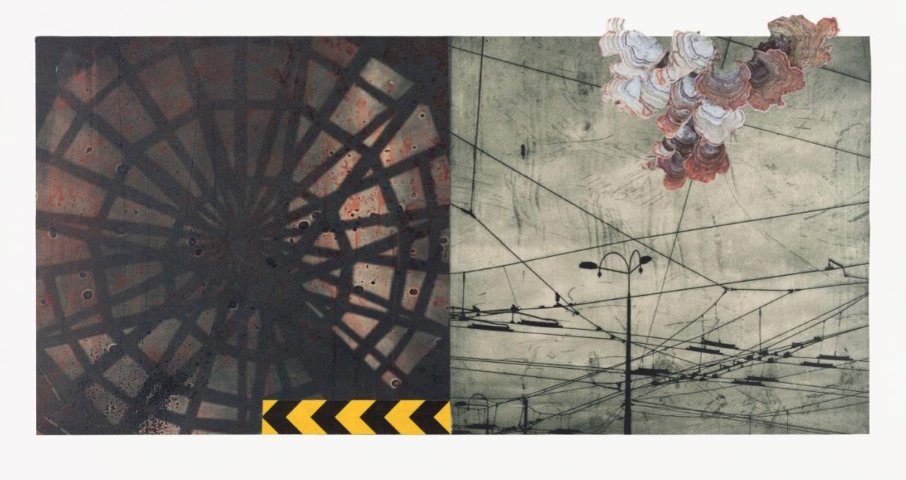

"These days, we have all become immigrants: we can clearly see the destruction of life on the planet that is our home, by the forces that seem overwhelming." Indeed, in this dramatically evolving society -- tremendous technological developments & our short attention span with longer life span -- how we find who we are and how do we adapt new methods into our old habits to create a better society? Immigrants who experience multiple cultural backgrounds have experience with this process, because for them, adapting to American life means they have built new life methods onto their comfortable, familiar foundations. In other words, immigrants are really ready for this future normal. Therefore, I understand why Softić introduces Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing (American anthropologist) and Lebbeus Woods (American architect) the way they did. Tsing sees human community as a fungal network, and Woods observes how we make homes by adding new material to distorted buildings after wars. Artists often find an idea from unrelated things. Artists are scholars, like Isaac Newton who compared a falling apple with the moon and crafted the theory of gravity. Softić is masterful at connecting those dots -- disintegration of her native country of Yugoslavia, Japanese-washi-paper, Covid-19, American social issues, chicken foot in a street drain -- to create her visual masterpieces. Tanja Softić Landscapes for the Last Century My visual art work combines the media of printmaking, drawing, photography and collage. I started writing poetry in my mid-forties. I should probably say “again and, this time, in English” because I used to write it in my youth, in Serbo-Croatian. Depending on who you talk to, this language is now called Serbian or Croatian or Bosnian or Montenegrin—I choose to stick to the nomenclature of my school days. An immigrant to the United States from Bosnia and Herzegovina, I have been working with the ideas of memory and migration for about twenty years. When I came to US in 1989 for what I thought was a three-year graduate program, I came from the country called Yugoslavia. So, while I am fascinated by questions of cultural identity or cultural belonging on an intellectual level, I have a personal experience of what Edward Said called the contrapuntal reality of an exile: I have transitioned through three citizenships in addition to one period of being a citizen of no country. In both my new and old homelands, outdated notions of national and ethnic identity and belonging continue to shape the politics and the society. Unlike many people affected by the current pandemic, by storms, fires and crop failures due to climate change, by capitalist boom and bust economies, I have had a privilege of having the safe, creative haven to process the events, record my thoughts and make work that is informed by the situation. Perhaps this privilege is not something that I would have noted some decades ago, but I am acutely aware of it now, and I am grateful for that awareness and sobered by it. Thinking about death, survival and their meaning in the larger cultural and ecological contexts and witnessing what may be the first death throes of the neoliberal world order, I have been working on Plague Diary, an ongoing series of collages on small sheets of kozo paper. The shapes I kept coming back to either embodied nature's ever-adapting ways of insuring survival, or cartoony visualizations of disaster. These days, we have all become immigrants: we can clearly see the destruction of life on the planet that is our home, by the forces that seem overwhelming. Each action we take and every contemplation of the natural world is tinged with sense of loss of our world as we know it and knowledge of how much we are losing every day to the climate change. How many autumns do we have left to observe the splendor of of turning leaves? How many species will disappear this year? How long before homes of millions of people and the territories of entire nations become submerged under rising waters? There is a sense of anger, despair and even helplessness in the face of inaction of world leaders. How do we articulate these feelings and this new way of experiencing the world so that we can communicate it? And how do we turn them into something actually useful, a new, creative way of looking at and reorganizing the world? Dreaming of the perfect past and simpler world is tempting, but it is fanciful: exactly whose simple past are we talking about? It is also useless. What if we learned to think about the loss not with nostalgia and mimicry, but aiming to understand the forces that shaped the culture and society then, in order to understand the inertia and fear that prevents us from seeing the value of alternative views or solutions to existential problems we are facing? The processes used for creating images for Plague Diary and my larger works on paper, involve material labors of walking, collecting, repairing, cutting, transforming and connecting, generally speaking. Specifically, I travel, hike and explore memory sites in order to create photographic material, I create photopolymer etchings from my photographs, I collect biological illustration, elevation maps, things like visualizations of meteorological data or geophysical forces, I cut and reassemble photographs and found images into collage works that are then further developed in drawing, print and collage. Almost always, I work on Washi--Japanese paper-- because it will hold the most delicate drypoint or aquatint mark as well as the densest mezzotint. In drawing, I use it for its versatility and its strength. Because of the length of the fiber, Japanese paper will endure the handling and folding that would turn any Western paper into a pulp. The processes themselves, the physicality of paper and drawing media, writing poetry, the visual sources I use all inform these works. While my poetic text is not obviously embedded into images, there is a vital connection, a symbiotic relationship between them: either the images generate poetry or the poem-writing provides insights that guides me in developing visual works. Night Blooms series of collage prints, for example, has been developed at the same time as some of my “Sarajevo poems”, such as Sarajevo Parataxis. Photographs of memory places interact with other elements (parts of old prints, traffic signage, photographs of mushrooms) in a visual, semiotic and lyrical ways: The city has a color in a way I aim to create landscapes for 21st century, include the loss, displacement and impermanence, but include hope as well. The works are unsettled and without the center because they investigate the world without center, without solid ground, without permanence in the lives of increasing part of humanity. My graphic interventions on top of the larger backgrounds are a conversation with that reality, they are investigations of our priorities and they contemplate new ways of living, valuing and thinking in this new, rapidly changing world. My visual work is also informed by the artist book formats I have observed and created, multi-channel video installations and other strategies to disrupt and alter the expected narrative. It is built as a result of digging into my own archives of photographs of mushrooms, invasive plants, memory places in Sarajevo and elsewhere, illustrations, decorative patterns, diagrams, maps, medical illustrations, microscopic imagery etc. Ultimately, this new work comes from what has been the impetus behind much of my art and writing: what is it that emerges as fertile, as full of possibility when we look back at life and culture that has been lost. How can we recognize seeds of renewal in the midst of unfolding disaster? For a couple of years, I have been working with images of mushrooms and invasive plants, incorporating them into my work as signifiers of the strangeness and interconnectedness of life and unexpected growth in unlikely places, as well as metaphors for displacement, migration, and assimilation. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, raises questions and offers ideas about sustainable life in the precarity of the Anthropocene through many distinct ways of looking at a species of mushroom, tricholoma matsutake: its biological symbiotic relationships, its role in processes of reforestation after disasters or logging, its vast underground fungal network, the communities and fringe economies it makes through foraging, trade, and global supply chains.(i) If I had to describe Tsing’s book in the ways one would describe a painting, I would call it a brilliant collage that plays with the notions of perspective that reveal not just deep mastery of it but also the need to escape perspective’s dictates and enter other means of envisioning pictorial space and what it is supposed to hold: “Without stories of progress, the world has become a terrifying place. The ruin glares at us with the horror of its abandonment. It’s not easy to know how to make a life, much less avert planetary destruction. Luckily, there is still company, human and not human. We can still explore the overgrown verges of our blasted landscapes—the edges of capitalist discipline, scalability, and abandoned resource plantations.”(ii) Another of my influences is the late visionary architect and artist Lebbeus Woods. In his book War and Architecture,(iii) he uses the term “scab structures” to refer to additive repairs to a broken building that call attention to war trauma and serve a distinct purpose, enabling new forms of habitation while witnessing the processes of destruction and repair. In terms strikingly similar to Tsing’s, Woods not only offers critique of capitalist architectural and urban planning practices that are based on the concealment of trauma and brokenness but also offers a vision of the more complex, more collaborative world in the aftermath of war or a natural disaster. “Architecture and war are not incompatible. Architecture is war. War is architecture. I am at war with my time, with history, with all authority that resides in fixed and frightened forms. I am one of millions who do not fit in, who have no home, no family, no doctrine, no firm place to call my own, no known beginning or end, no “sacred and primordial site.” Both Tsing and Woods visualize a habitable, sustainable communal world where brokenness is acknowledged, openly mourned, and woven into the landscape. We build upon the past, they acknowledge, but they warn us that nostalgia, sentimentality, ideas of “innocence” of past cultures and societies are slippery grounds to build upon. Preservation of memory without resorting to outdating solutions and concepts is possible: attention, as Simone Weil has said, is a form of prayer. And I would add, is the beginning of understanding, conversation and action. As an artist, I am hearing both Tsing and Woods inviting me to practice attentive, creative openness to a shifting terrain and its surprises—not unlike the kind of awareness one would need to forage for mushrooms, cross the sea to uncertainty in a flimsy boat, or set up home in the ruins. That is where the hope is. And that is how I hope to create the landscapes and portraits of precarious world-- decentered, polyphonic, surprising. If we listen, carefully, to the stories of migrants, exiles, and refugees, not only for the sake of exercising our compassion but in order to learn ways of coping and rapidly evolving by witnessing the unthinkable. Popular culture is replete with figures of tough lone survivors in a postapocalyptic world, with a gun and a supply of food cans. Actual survival on the Earth will call for much more complex thinking and actions. In this work, I reach back into my visual archives, I try and listen to the present and envision the possibilities in the future. Notes: (i.) Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015). (ii.) Ibid., 282. (iii.) Lebbeus Woods, War and Architecture, trans. A. Wagner (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002), 1. Tanja Softic´ works in the media of print, drawing, photography and poetic text. A recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Grant, Soros Foundation Grant and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, she is currently working on a series of works of paper that examine migration and entropy, both in nature and in the human society.

Her work has been exhibited and collected by museums, libraries and galleries worldwide, including the Library of Congress, National Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Department of State Art in Embassies Program. She completed print projects at Flying Horse Press, Tamarind Institute and Anderson Ranch Print Studio. Her work was published in Southern Review, Hourglass Magazine and a number of academic publications. She teaches printmaking and the art of the book at University of Richmond. Poets are hard trainers (Period)

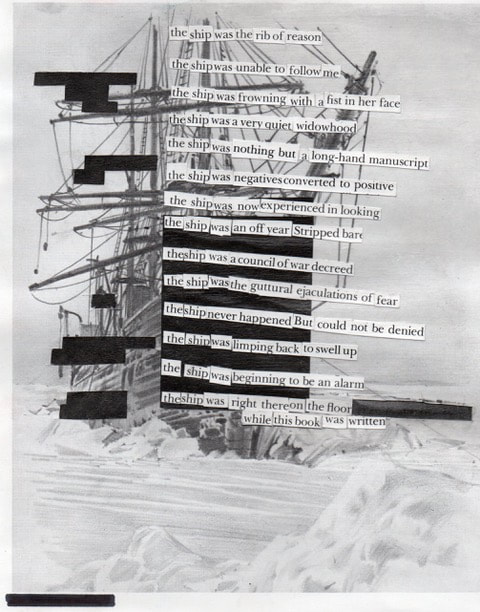

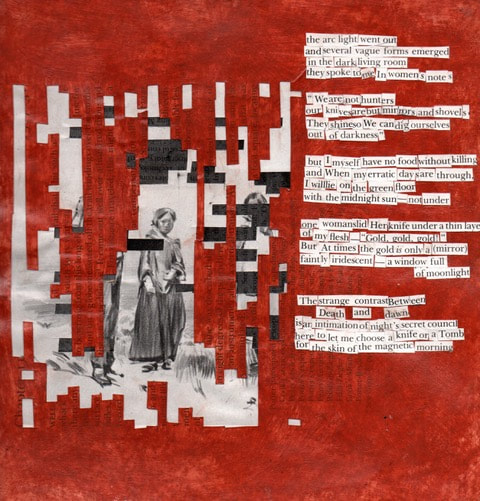

It can be more relatable to observe athletes at the 2021 Tokyo Olympic & Paralympic Games; instead, poets are, perhaps, like Auguste Rodin's The Thinker. Poets reach the limit of ones capacity - - write, erase, re-organize, destroy, create again, and then the final product - - though the products may not be well received by audiences. They may be overlooked or invisible. I do not think that it is an ideal environment for our creative selves, it is one that may lead to self-doubt and wrong impressions about our creations. However, the process is part of poetic progress. In other words, we - - poets - - have to find the optimal balance between our perception of our work and its reception. Ina Cariño, Kylie Gellatly, & Mary Ruefle (her essay is shared by Gellatly later in this article) have similar sutras for this. I think I’ve finally made peace with the fact that things take time, and that time takes time, too. - - Cariño You haven’t even begun. You must pause first, the way one must always pause before a great endeavor, if only to take a good breath. - - Ruefle When I reviewed Gellatly's book at RHINO Reviews, I was immediately curious as to why she adapted found poetry with art, and why she chose that original source, The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter. I was not expecting such vivid details. The Fever Poems by Kylie Gellatly The Fever Poems is the result of a myriad of circumstances; including but not limited to a head injury, a bad case of hives, the (then new) Covid-19, and a big move. I am tedious when telling the story behind this book, as it feels romantic in a way that I feel timid taking credit for. Maybe that is the nature of found poetry. Trying to tell the story of how this book happened is like trying to scoop a pile of shapeless things, or oozy goo blobs, into my arms and then try to carry them some distance and make an eloquent hand-off. What shape would you give to a head injury, hives, the pandemic, lockdown, packing up an apartment, the protests, isolation, the feeling that all I have is everything I have and is everything I will lose. How to contain this: The Fever Poems was a towel to clean up a spill, or a vessel—the kind of vessel that a towel becomes when it is entirely saturated. I had been working on a collection of poems and had just discovered the through-line, that the poems were about grief of self, or past selves. Then came the breath, the pause, the prescription: no screens, rest your brain, your eyes. Then, a physical enactment of the grief that I had recognized, under the circumstance of not knowing whether I would be able to restore my brain function to what it was before. The head trauma I was recovering from was one that had, at first, subtly hindered my ability to comprehend what I was reading, but under pressure, led to trouble with comprehension in both reading and writing. I was prescribed a month of rest and given strict parameters around what my brain could handle. I mostly just wrote letters to keep in touch and found so much creativity in this communication, which asked for something to be made in order for it to be said. I was drawing and collaging and writing a lot of letters, long letters, to various people; carrying on these disjointed conversations over gaps of time and distance. I think of Mary Ruefle’s essay “Pause”, in which she says, “You must pause first, the way one must always pause before a great endeavor, if only to take a good breath.” The choice to use The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter started with reason and turned into another. At first, it was simply that I was preparing for a move, cleaning out my books, and questioning whether I would take this book to another new place with me. My collection of arctic literature had once been very enthusiastic but, by this time, Porter’s diary was the only one left. I had carried it around for years for sentimental reasons and for a very dear inscription inside. I thought, it can only come with me if I make it into something else. So I tore out the inscription and started pulling the book apart. My obsession with arctic literature was an antidote for a steady depression and had presented itself to me as a form of escape that bred optimism toward endurance, stamina, and unlivable conditions. The nature of this use became poignantly clear to me as the nature of its escapism and toxic kind of endurance pointed at a lot of the shame I had been carrying. The book became a symbol for a fixed narrative, something I had been keeping my fragmented selves inside of, on ice. In retrospect, the best way I can think of the creation of The Fever Poems is as a month-long play in which I enacted an homage to the grief I was holding inside me for every person I had been in my life and a deconstruction of the walls that I held around each of them. Instead of leaving a pile of rubble, these collage poems are mosaics, made in a fit of compassion, that create a myth all its own, starring a fluid “we” and “I” — sourced from the context of Porter either speaking for himself or on behalf of his crew — to meld into a single, whole, and present form. Creating one poem every day for a month suspended judgement, doubt, and question long enough for a trust in myself and my voice to grow. Kylie Gellatly is a visual poet and the author of The Fever Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2021). Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in DIAGRAM, Tupelo Quarterly, Iterant Magazine, GASHER, Literary North, Palette Poetry, and elsewhere. Kylie is the Book Reviews Editor for Green Mountains Review, Editor-in-Chief of Mount Holyoke Review, and is a Frances Perkins Scholar at Mount Holyoke College.

I often receive two questions:

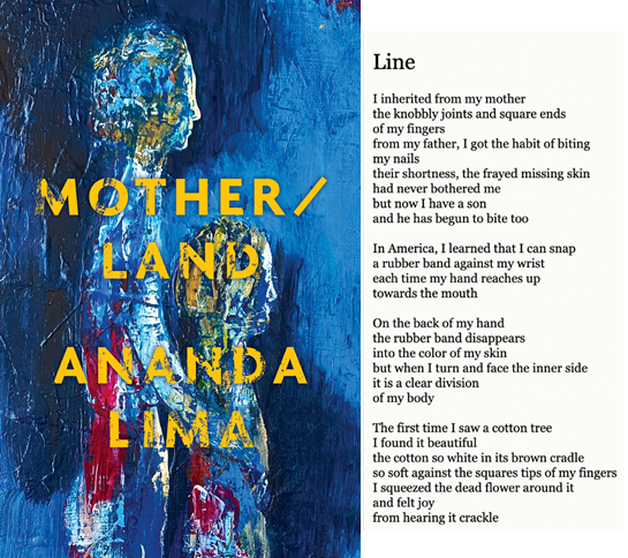

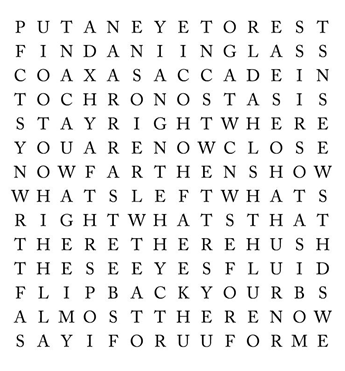

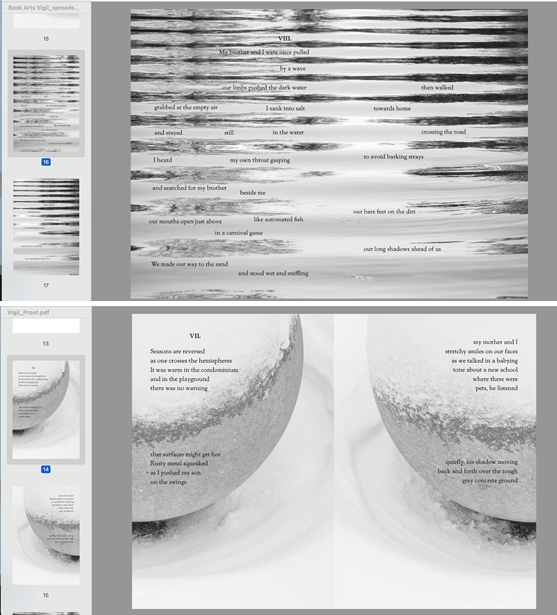

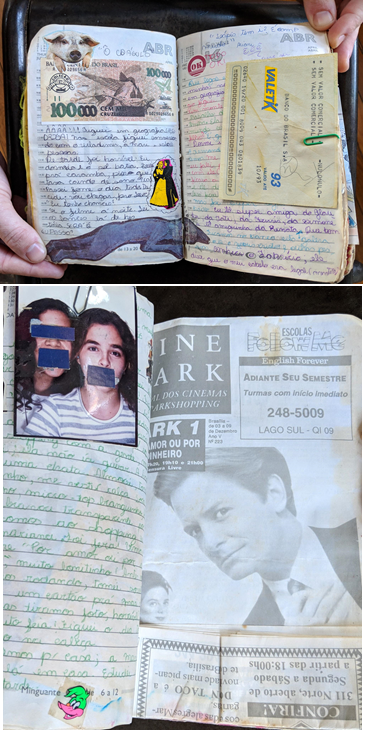

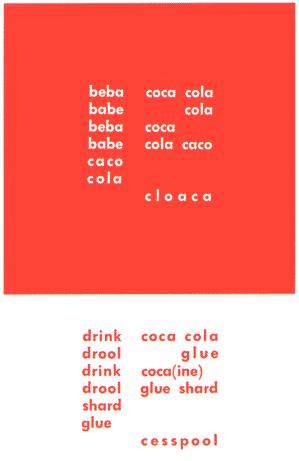

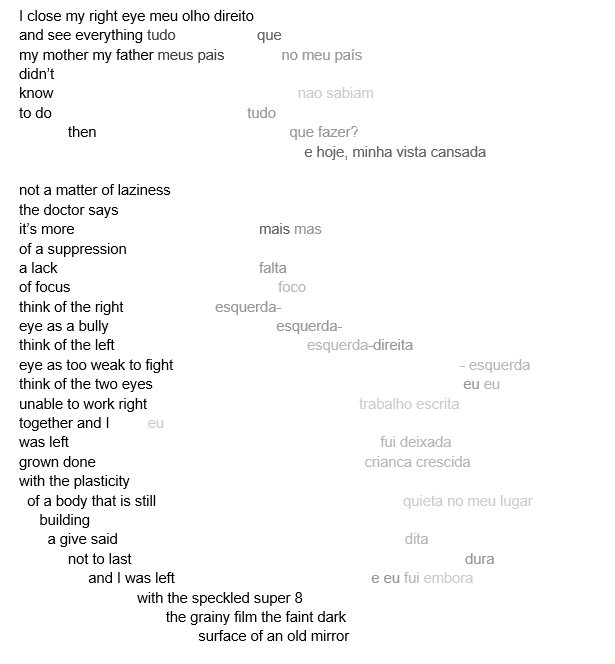

To be honest with my audiences, I am annoyed by these questions because the answer to the first question is always, "yes," and the answer to the second question is always, "Leaning a craft takes time". When I read Ananda Lima's essay, I understood why they asked me these questions. Creating new approaches to poetry (even though there are many historical examples, like Brazilian Concrete poetry) can be lonely. Finding a graphic & visual poetry tribe can be trying, as if you are cutting through a bamboo forest to find treasure. I again realize how important it is to connect with communities and share knowledge about graphic & visual poetry at the Working On Gallery. Some poets may just be apprehensive to step into unfamiliar territory. Now, if they ask me these questions, I say, "Yes. Come join us!" However, drawing & collaging art do not create a good graphic / visual poem. Borrowing Lima's word, "intuitive", is a part of the process - - you develop a feel for what works in your vision, your decisions are made with more confidence - - though, the intuitive ability comes after studying text poems. It is a long journey, but exciting. I found a new tribe member today. What am I doing here? Brief notes on being invited to hang out with graphic poets, and maybe line breaks By Ananda Lima As a poet, so much of the knowledge I have of my poems-in-progress or finished poems is intuitive. A knowing about whether something feels right, if it is doing what it should be doing, that is, ironically, apart from anything verbal. But a knowledge that is very much real. It might be only much later, often after the poem has been finished for a while, that a more verbal understanding might come. When asked to talk about a poem in an interview, discussing it with an editor, or talking to a friend, a verbal explanation might arise. An editor might wonder if a word should be shifted or cut, and only then, I develop a verbal understanding of why a specific word is part of the structure that holds what is underneath the poem, a structure that might not be entirely visible when skimming the verbal surface. Or a friend might make a connection that I had not expressed verbally, even to myself, but that I knew in some pre-verbal way was there. It's fun when I see those things come out in words. It can be illuminating. It can create new connections and generate new verbal or intuitive knowledge. It can make me feel understood. But it is always partial, tentative, not corresponding exactly to that non-verbal knowledge. This too can be satisfying/good news: if the poem can be paraphrased exactly, then it probably is not doing all it could do as a poem. A good poem, as a good story according to Flannery O’connor, should resist paraphrase. In a similar way, when Jennifer Sperry Steinorth asked me to join an event with a group of graphic poets and visual artists, including herself and Naoko Fujimoto, my membership in the group felt but intuitively right. This was despite the differences in the type of work members of the group were doing: there was brilliant and fascinating art that literalized and reinvented erasure while undoing a literal historical erasure, poems as transsensorial translation; a visual and sensory richness with mediums that included paint, white-out, lace, embroidery, and more, as well as words. Whereas I was had been keeping myself busy writing mostly good old regular text poems: (Though often these were poems where the visual played an important role.) Despite the contrast between the visual and medium complexity of the group and mine, I was only intimidated in the usual ways (ie, speaking alongside amazing people whose work you are very impressed by). But I did feel that I belonged with the group. Though I couldn’t initially verbalize why. In preparation for the event, I went searching for that verbal knowledge, trying to understand my feeling of belonging in the group. It wasn’t just that I was, separately, a photographer, as well as a poet. Or that I sometimes put photography and poetry together. It wasn’t just that I had been interested in the friction that words and visual objects create in the page for a long time. It wasn’t that as a child I was introduced to Brazilian Concrete poetry alongside sonnets and ballads and thought of them collectively as just regular poetry: (Or that somehow concrete poetry for me is emotionally entangled with concrete concrete, as in cement, the concrete of the Brazilian modernist architecture from the 1960s and today. Or that geometric, intentionally graphic or brutalist concrete structures around the world transport me to a time and place that only exists inside me, bringing me home. Or maybe all of that was part of it, but there was something else, more fundamental. I felt connected to the work of those graphic poets in a more abstract way, which is less dependent on a specific medium or specific biographical events. I started thinking about the poem I would discuss with the group, “Amblyopia”: Despite reading it out loud in different ways in the drafting process, when it came to reading the finished poem, I just knew what to do. Again, that knowledge was fully present, but purely intuitive. I read the solid left side of the poem out loud, as I would any poem. But I only read the first two lines or so on the right side, letting the rest fade away into silence. That way of reading felt very right. It was both part of how the poem was saying what it wanted to say and what the poem was saying. And seeing that how and that what intertwined is what I want to see in a poem. As it often happens when thinking about poetry, all of this lead me to to line breaks, a fundamental feature of poetry (maybe even prose poems, in their opposition to the line). The line break is an additional meaning making element which interacts significantly and meaningfully with the verbal, but is not itself verbal. It can be combined to reinforce or be in tension with verbal language, a wrestling for breath between break and syntax. Somehow the line break and that intuition about how to read “Amblyopia,” more than those explicitly visual art factors I mentioned before, were at the heart of why I felt I belonged with that group of graphic poems. Something about how the sound and the visual presence of text in the page sometimes reinforced each other, sometimes were in tension with each other and created meaning from their interaction. In graphic poetry, there is often a verbal component, words that have a stronger intrinsical link to sound, that can be read verbally without appeal for description. And there is the visual and/or tactile component, which “speaks” non-verbally. The poems are made of the two components working together to create something that cannot be simply replaced with description. In other words, graphic poetry is poetry. And it is poetry that makes that non-paraphrasable quality of poetry, fittingly, more visible. Verbalizing this, I am beginning to understand why graphic poetry, concrete poetry always felt to me, deliciously, a little meta, a little ars poetica, and very boldly poetry, even when the subject matter is not poetry or the poem itself. So the reason I felt I belonged there had less to do with the fact that I was also a visual artist, and much to do with the fact that I was simply a poet. A poet that cannot and does not always want to explain her poems. It had everything to do with that non-verbal factor that is essential to poetry, and a poem’s resistance to paraphrase. And there I felt right at home. Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land (Black Lawrence Press) is the winner of the Hudson Prize. She is also the author of two poetry chapbooks (Amblyopia, Bull City Press, and Translation, Paper Nautilus), a fiction chapbook (Tropicália, Newfound), and a poetry and photography chapbook (Vigil, Get Fresh Books). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark. You may also like reading: