|

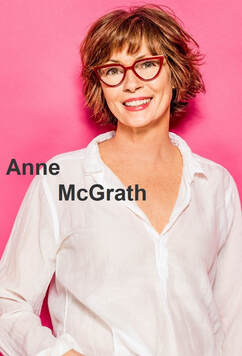

I became familiar with Anne McGrath's works when I ran Working On Gallery's Instagram account. During the pandemic, she posted a piece every day -- some were black & white paintings, some were naturistic adaptations -- it became my morning routine to observe her art with a cup of coffee.

Today's process essay especially encourages me because I have been thinking of how much I have yet to achieve in creative writing. During the pandemic, I was really thankful and lucky to survive as a poet & artist. Though, I also realized that I was becoming a professional creator who has to be flexible under many circumstances. I likely burned out, because my mind told me, "I don't want to read or write in English anymore!" "Then the pandemic lock-down hit and I found myself at home with time and a small tray of my son’s leftover watercolors, crayons, and markers... At the risk of making a fool of myself I posted one of my creations on Instagram." I would like to express McGrath was a nonfiction writer. She started painting when the pandemic started about two years ago.

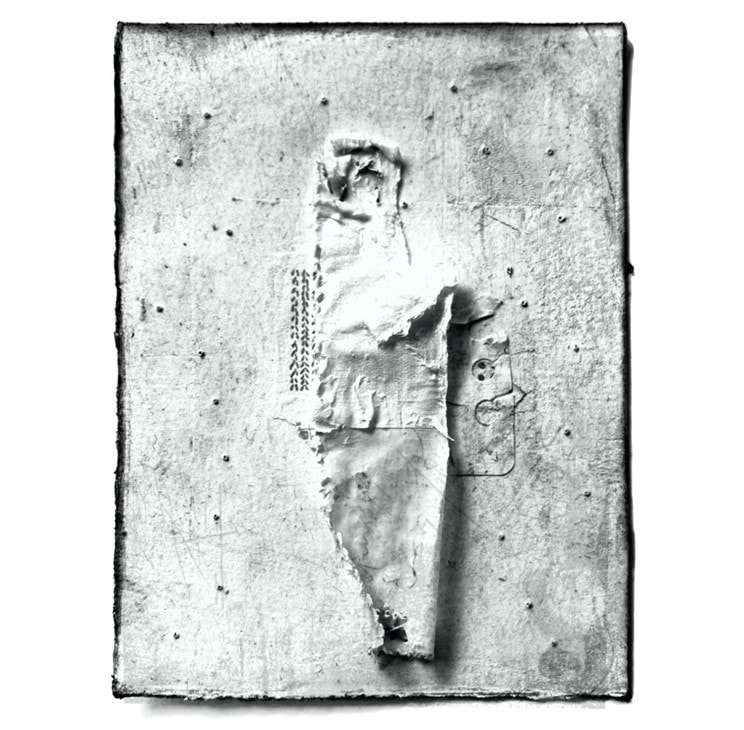

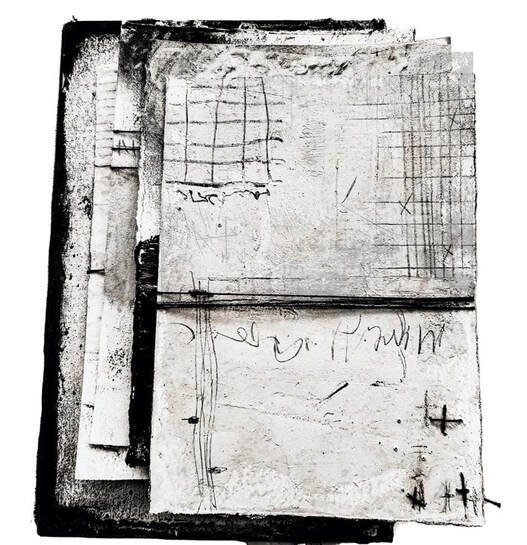

My past contributor, Luisa A. Igloria (the Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia), also started creating three-dimensional art & writing pieces. Now she publishes her crafts. In addition, she is organizing a Poetry Postcard Project this National Poetry Month. I noticed more and more that writers jumped into different genres like paintings, playing music, practicing yoga... and many of them started new professions in addition to their existing writing careers. "At the risk of making a fool of myself..." What kind of risk can I take to further myself? I create graphic poems and play the piano. Why do I -- write in Japanese -- don't I? You may be thinking it is your native language! And you'd be right. But I have never seriously written stories in my mother-tongue. Now, I am writing something in Japanese everyday. This is how we -- writers -- keep building on our craft: at the risk of making fools of ourselves. Essay by Anne McGrath Having been crushed by art teachers early in life, I was as frightened of drawing as I was of taking the math portion of the SATs. Humiliating attempts at making art had revealed my inability to create anything resembling anything I was aiming for. By the age of six I’d written an obituary for artistic endeavors. Then the pandemic lock-down hit and I found myself at home with time and a small tray of my son’s leftover watercolors, crayons, and markers. I started scribbling, collaging, and experimenting with mark making using bright colors and wild lines. At the risk of making a fool of myself I posted one of my creations on Instagram. I connected with other artists and posted another, and another, and I have made and shared some form of art nearly every day for over two years now. I began trying every art form that caught my fancy. I hand-sewed textiles into little booklets made of scrap fabric and left them covered in dirt for months to deconstruct their surfaces. You never know what you’re going to get! I buried the one pictured above in the fall, dug it up in early spring, and washed it in a mudpuddle. It was underground through rain and snow and had delightful little squiggly marks on one page where a leggy bug had roamed through. The process was meditative and joyful, which is how I now think art making should be—full of wonder. My pile of vintage books was perfect for making erasure poems. I was amazed when gorgeous literary journals like Thrush, The Indianapolis Review, The American Journal of Poetry, and The Ilanot Review agreed to publish them. I bought several Pilot Parallel pens and discovered the bliss of asemic writing—placing brush strokes on paper to form words without regard to logical language structure. It was thrilling to let my imagination run free and I had no problem looking beyond the illegibility of my writing to find beauty and inspiration. I was writing nonfiction before the pandemic but stopped to focus on worrying and am only now returning to a semi-regular writing process. My visual art practice—now mostly in black and white— has expanded the way I perceive the world and I’m hoping this shift will inform my writing. It’s easier for me to see value gradations in a limited palette and I want to approach words and sentences in a similar way, to keep things clean, to add wonder and meaning in layers. I’ve learned that using a range of values—light, medium, and dark—makes my visual work more interesting. I can create an energetic mood using strong contrasts or I can create a sense of calm using more subtle variations. I want to bring these nuances and juxtapositions to what I write. Something as simple as using different values in a piece reveals visual texture and a sense of depth which can be used to lead the viewers eye around a canvas or a page of text. Depth and texture might be added to writing by alternating big and small voices and varying the lens from closeup to distanced. If I can pair down my palette and my expectations for my writing, be open to taking to risks as I did with my visual art, I think I’ll find more satisfaction in the process. Anne McGrath was noted in the 2020 Best American Essays series, she was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and she was the recipient of fellowships from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She has work published or forthcoming in Creative Nonfiction, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, Ruminate, Entropy, Columbia Journal, The Writer's Chronicle, and other journals.

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024