|

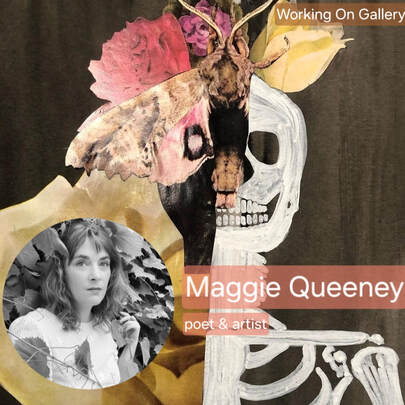

I got to know Maggie Queeney through the Poetry Foundation because I was one of their visiting artists in 2023. She facilitated and organized online workshops and events. Her learning prompts are available at the Poetry Foundation's website. They are great tools to use for classroom and individual settings.

It is incredible to host free lectures for people from all over the world so they can learn about poetry. I also met students from India and Great Britain. Queeney has contributed significantly in building our global art community. It is a safe and welcoming environment for everyone who wants to learn.

I finally met her at the 2024 AWP in Kansas City. She came to a panel for The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Graphic Literature with Kelcey Ervick, Nick Potter, and Lauren Haldeman. After AWP, I was wondering why I was excited to talk about words and images. Where do I want to head with fellow writers who practice art? It is corny to imagine, but we are running toward a bright light, though it is so vague.

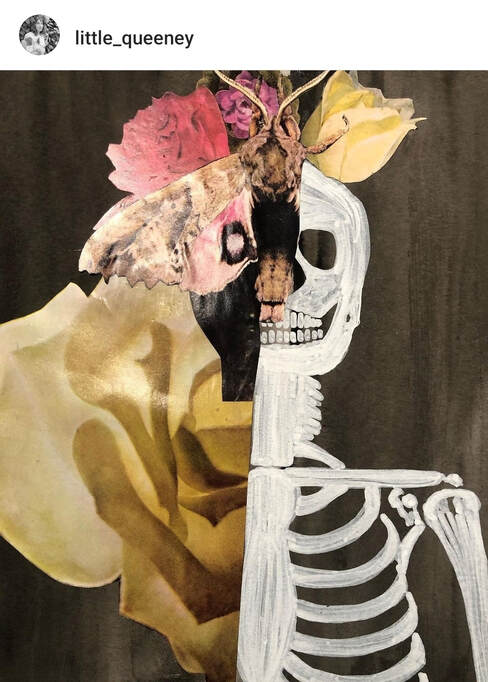

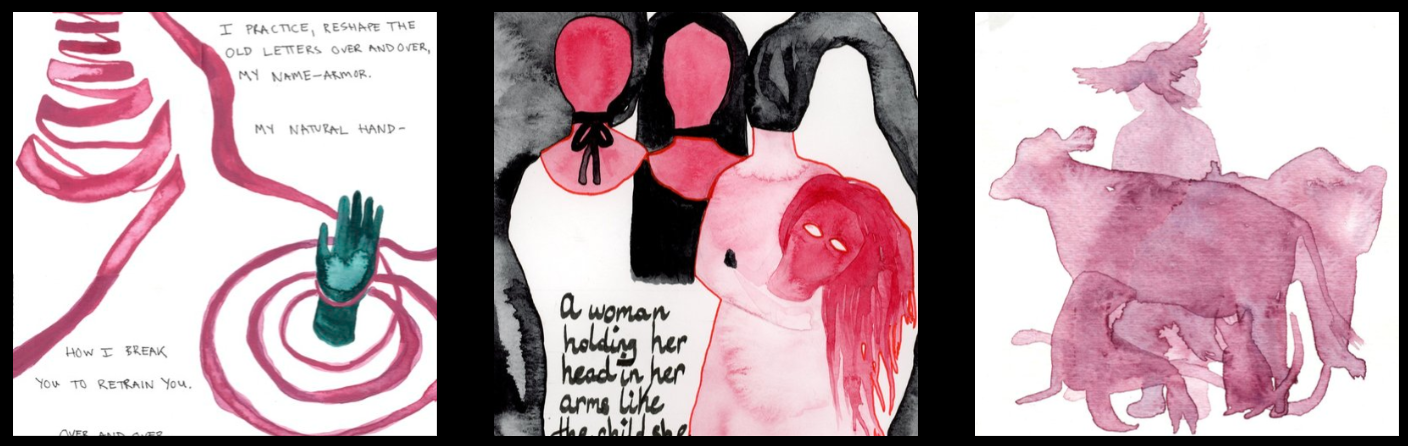

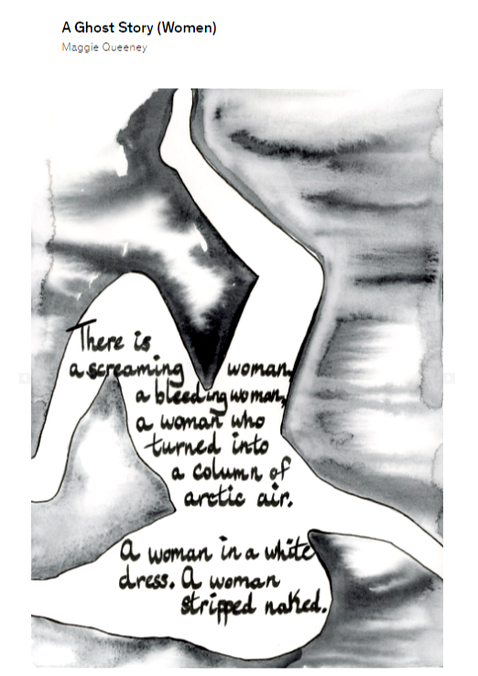

"I leave my body and enter the world created in language. The present the body exists within can be left behind." - - Maggie Queeney We live until our existence fades, as it should (which is so simple); so does our creativity. But it often gets lost between the Yin and Yang. How can we block out the noises around us to enter a world governed by language? How can we merge with "the letters inside the words as mine." Her book In Kind, winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, is forthcoming in 2023. In 1990, when I was eight years old, beloved children’s author Beverly Cleary published Muggie Maggie, a book about another eight-year-old girl who refused to learn to write in cursive. I never resisted drawing the strange, ornate characters over and over during cursive practice. I could compose each letter, but when asked to write whole words, then sentences, then paragraphs, I struggled to reproduce the loops and staffs, hoops and turns. When tasked with turning shapes into strands of meaning through the black and blue rules of the notebook page, my hand still tangles, trips, and scribbles the words illegible. In 1992, when I was ten years old, I was diagnosed with PTSD. Now, my health care providers type Chronic PTSD or Complex PTSD into the dedicated glowing square of screen. Neither diagnosis officially exists. I have to work to write sentences another person can read and understand. I am told my handwriting is bad, poor, illegible. I am told that the purpose of writing, of text, is to communicate with another, and I am failing. In my first eight years, I had only heard the word muggy used to describe the heavy, hot late summer. It was not a word for a girl with my name. I did not understand how the main problem in her life was learning a new way to write. How, in my memory, her fear of cursive was really a fear of growing up. For her, childhood meant familiar, safe. I knew each word, could write each letter in my own cursive, but I did not understand Muggie Maggie (the character, the world in the book, the story). The book could not communicate to me, but I knew, even then, that I was the one who was failing. Dr. Judith Herman, the first researcher and scholar to recognize and name my particular species of PTSD, begins her seminal book Trauma and Recovery by noting that trauma is, by its very nature, unspeakable. When worried or agitated or scared, I tic. I clear my throat a dozen times a minute. A thousand times an hour. I tic in my sleep, depending on the dream. I want to know what it is like, to want to remain a child. To live without this invisible bite always digging. Dream interpretation would say there is something I need to say that I cannot or will not say. Dream interpretation would say that I am choking on what I cannot or will not tell. Dr. Herman notes: As a child, folded into the cold school desk, I filled the margins of my notebooks in eyes, wolves, snakes. The breasts and necks and heads of women in profile. Their elaborate hairdos. Lightning and roots, tornadoes and disembodied hands. Birds, eggs, trees, and nests. When do writing and drawing become different practices? How can I know, bent over the blank field of the page, whether I am drawing or writing? What decides: the body or the mind? A defining symptom of my disorder in frequent, severe, and uncontrollable dissociation, a state where the body is separated from the mind. A disassociated child can barely register a blow to the head, so far away she is from her soft body. A state of dissociation can be induced by writing. I leave my body and enter the world created in language. The present the body exists within can be left behind. Drawing, I am made to stay in the present. My mind slows to the speed of my hand and other materials: ink and paper, paint and pencil, blades and glue. When I draw each letter, I am made to consider each letter, each word, I write before I write. Made to mean what I mean. To consider what a wolf or root work or nest really looks like, and how to arrange each part into the whole of the page. I can stay inside a body engaged by the hand and the eye, recognize the letters inside the words as mine. Maggie Queeney is the author of In Kind, winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, forthcoming in 2023, and settler (Tupelo Press). She is recipient of the Stanley Kunitz Memorial Prize, the Ruth Stone Scholarship, and two IAP Grants from the City of Chicago. Her poems, stories, and hybrid works have been published widely. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Syracuse University. Working On Gallery Past Guest Editors: Luisa A. IgloriaMeg ReynoldsFrancesca PrestonLúcia Leão Your $25 donation will be a tremendous support for Working on Gallery's future guests and running costs.

If you become a patron, your name will appear in the next Working on Gallery's article. In addition, you will receive my first poetry book, "Where I Was Born", for U.S. shipments. Or, you will receive a thank-you letter for international shipments. Working on Gallery has been used by universities, advanced-level art lectures, and writing workshops. Your donation will help this gallery be more successful. Thank you so much - Naoko Fujimoto |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024