|

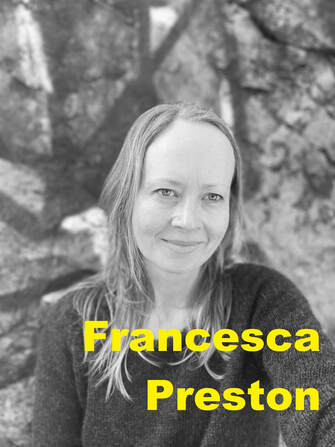

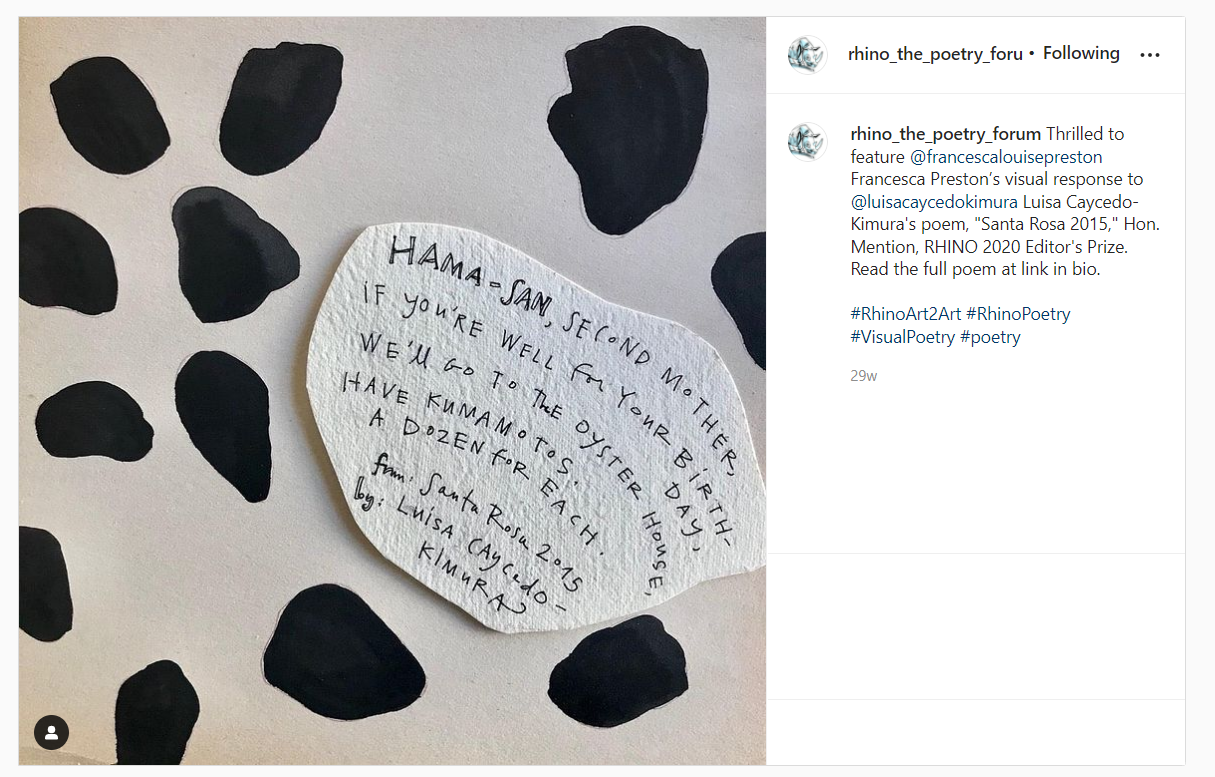

First time I saw Francesca Preston's works was when she submitted her piece to RHINO Poetry. She added images to Luisa Caysedo-Kimura's poem, "Santa Rosa 2015" (RHINO Poetry, 2020). Her art was shared in RHINO Poetry Instagram. Later, we exchanged some letters and email, she told me of an article about Anselm Kiefer. I acknowledged him in my book, "GLYPH", because I created my very first graphic poetry sketch in front of his gigantic concrete pieces in North Adams, MA.

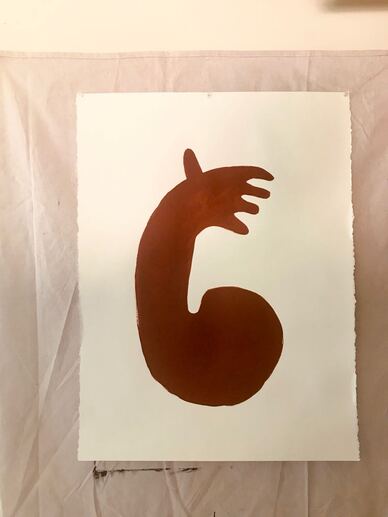

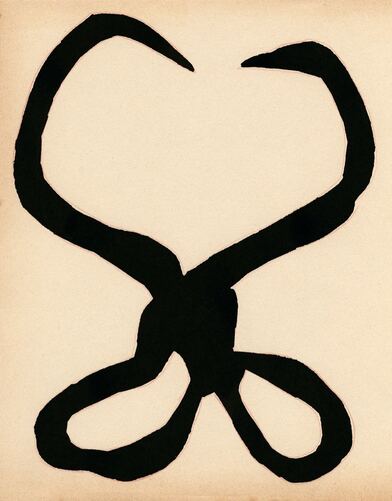

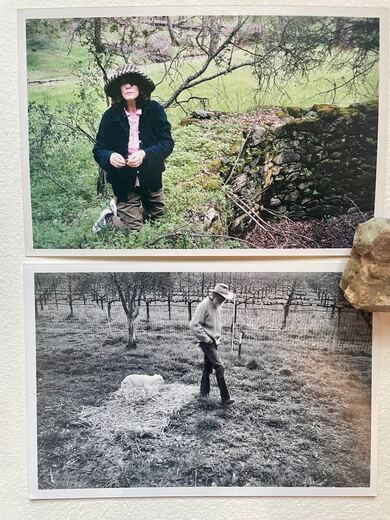

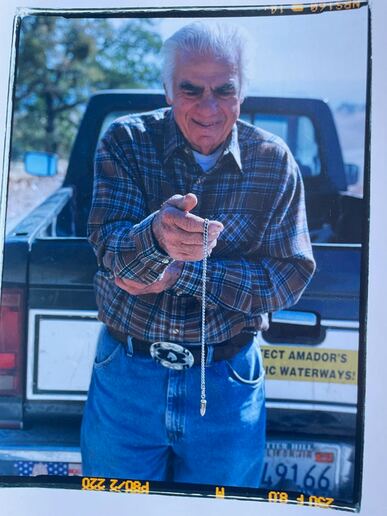

After I read the article (New York Times, Interview by Karl Ove Knausgaard, 2020), Keifer reminded me of Professor Calculus from the Adventures of Tin Tin. Both are genius, but oddly strange -- perhaps, like movements of a pendulum. In case you are unfamiliar with his pendulum, you may visit this Q & A website about How does Professor Calculus's Pendulum work in Tintin? Yes, it is weird. I used a pendulum when I was sixteen in the countryside of Oregon. It was my first summer visiting the United States by myself without any English abilities. I was there as a part of school activities or sort. I knew that it was a pendulum (thanks to Processor Calculus), but I still did not know why a young Japanese girl with no English-speaking abilities ended up walking in circles with a pendulum in the middle of nowhere. Where does this pendulum keep guiding me? From Preston's picture (in the very end of her essay), there is a pendulum with Tony Himan, Water Witcher. I assumed that he used his pendulum to look for signs of water. "The question of whether water witching actually ‘works’ doesn’t interest me. I know it works, in the way that I know poetry works. What does interest me is how a poet, an artist, or a water witcher tunes their body to their craft. Writing a poem, like looking for underground water, is feeling for something you can’t see – a fluid source, a mystery that cannot be truly comprehended. But you can use that source, you can work with it." I wonder if my pendulum experience connected me with today's craft essay. My Language Wants to be Seen By Francesca Preston I once spent time with a talented water witcher, a special man named Tony Himan. He’s gone now. He would be hired to dowse for peoples’ wells - still a common practice in the country. We stood together in the dry, rocky foothills of my grandmother’s land, and he showed me how he looked for water. On the surface it was simple – he was just holding a bit of dangling metal and walking around. Tony Himan was so good that he could tell not only where the water was, but how deep within ten feet, and what minerals were at certain layers: where salt, where iron. He was self-taught, and had spent years practicing in a big cardboard box out in the fields. He said it didn’t really matter what tool you used; in the end it was all about the relationship between your mind and your hand. You have to develop the rest of it. The question of whether water witching actually ‘works’ doesn’t interest me. I know it works, in the way that I know poetry works. What does interest me is how a poet, an artist, or a water witcher tunes their body to their craft. Writing a poem, like looking for underground water, is feeling for something you can’t see – a fluid source, a mystery that cannot be truly comprehended. But you can use that source, you can work with it. The comparison here is perhaps obvious. Word/image = water; writing/making art = tapping, listening, using your body and mind to locate, to place. But Tony Himan revealed something to me that I will never forget. He practiced in a cardboard box! The thought of him carrying an enormous cardboard box out into the fields, and sitting inside it while he concentrated with his mind, re-minds me of my childhood, and my inward-looking self. How the land tugged the fingers of his mind. I grew up in the country on a dead-end road. It was eerily quiet, and we had few neighbors. I spent a lot of time by myself, reading, drawing, and fantasizing about making 3-D houses out of white paper. Every once in a while we’d go to San Francisco and my mother would take my sister and me to an art museum. Eventually I noticed something internal: when I’d look at a piece of art on the wall, I would feel an intense urge to read the title underneath it first, or at the same time. My eyes would flick back and forth, out of my control, and I often couldn’t settle down. But when I looked at pieces where image and word, art and text, were fused – as with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Bruce Nauman – I felt my body relax and a sort of ecstasy emerge. It continues to be this way for me. I have a presiding obsession with the relationship between words and images, and a desire to have them together. More specifically: to rejoin them where they have been broken apart, back to their birthplace in the earth itself. In working on this essay I realized yet again that my art is the pictographic version of my writing: symbols that circle back to what I’m tracking or constructing in the verbal realm. My art is writing too. When I encounter unnecessary jargon in the world – dead, technical language used to alienate people – I get really angry. This type of language refuses to allow images in the mind, which I believe are essential to live. My language wants to be seen. These are old, blacksmithed ice tongs from the ghost town where my mother grew up, and to which my Ligurian ancestors arrived in the 1800s. I have never used them. There is no longer a need to lift heavy blocks of ice – cut from a pond! – in order to keep food cool. But the iron object, which resembles scissors or birth forceps or talking snakes, gnaws on me with its enduring presence. Hefting chunks of a frozen ‘body of water’ in order to keep something (that will be consumed in short order) seems related somehow to the act of writing – from fluid to solid to fluid again. Catching a thought-form in the right state, working with it as fast as you can, and then letting it do its own thing. * During the pandemic I’ve started listening to people more, or rather overhearing them. Perhaps it’s that the opportunities for stranger-exchange are fewer, so I am alert to any stray gems. A couple weeks ago I heard teenagers in a cafe discussing the holidays, what gifts they’d received, and the topic of gift cards. I heard one say, My family’s so weird. I had a massive laugh inside when I heard this. I love that she used such specific words (for a teenager, particularly) to describe what she didn’t want: tangibility, specificity, the physical evidence of choice. And I realize that is exactly what I do want in my writing, and my art. I want to use mysterious means to pull tangible and specific things out of the ground: coins, parts of old tools, bits of dialect, other peoples’ dreams, neglected words, uneasy memories, anything ancient. My poems are often dark-humored. It is no surprise to me that ‘humor’ originally meant ‘bodily fluid.’ The inner syrup of not only humans, but animals and plants, occupies me. No matter what I think I want to write about, there is often my family in the way, like a cow standing in the road on a warm night. By ‘in the way’ I mean part of the way; they are part of my work. By the time I was 10, my mother had fully become a painter, and would leave cryptic notes to herself around the house, things like ‘tiny, squash-eared babies’ or ‘precarious’ written twice. There were always words in her paintings. She walked on them intermittently, and then left them on the floor, where I would come to stare as if they were lost siblings. My father was (is!) a rebellious farmer who started baking bread when I was a child. The images of dough being kneaded and allowed to rest are visceral for me: flour and bread enter my poems regularly, like a kind of ghost. In a recent piece for the Ekphrastic Review I found myself describing my great-great-grandmother’s face: moon-wide as bread / squashed into a suitcase. The polarity of dough-rising (roundly expansive) and the truncated form it must sometimes take (boxy, contained) feels like what her life must have been, in shifting from one place to the next. My desire to retrieve things applies to my poems themselves. I have a chapbook coming out, {If There Are Horns, to be published by Finishing Line Press} after 17 years of not sending out poetry. I wanted to honor these older poems, written as I was navigating within and away from my family, away from academia, away from this country, becoming lost in an important way, and then back finally to the land of my ancestors. I wanted to give them a home, a suitable container, after all these years. Francesca Preston is a writer, artist, and editor based in Petaluma, California. She graduated summa cum laude from Amherst College, and then dropped out of two MFA programs in her twenties. Her poetic works have been published or accepted by journals including Ambidextrous Bloodhound Press, Crab Creek Review, Ekphrastic Review, Fence, Feral, MALUS, Phoebe, Walrus, and her essays by various magazines. The land she mentions in the essay, a ghost town called Calaveritas, is located in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Her chapbook If There Are Horns is forthcoming in fall of 2022.

Website: francescapreston.com |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024