|

I often receive two questions:

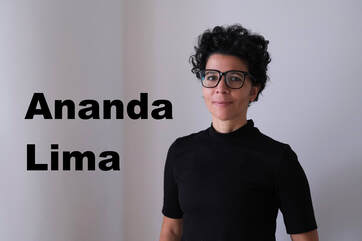

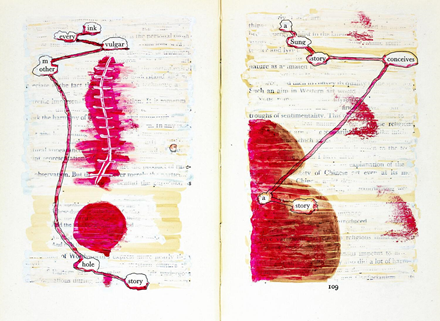

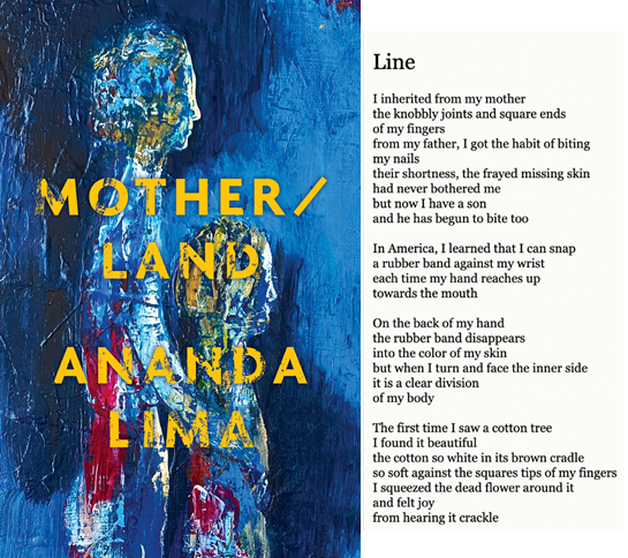

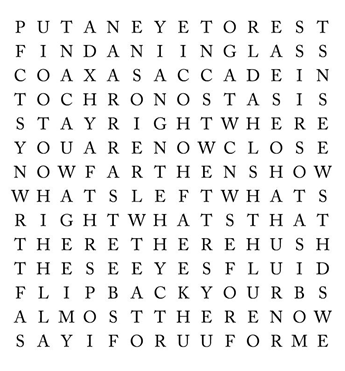

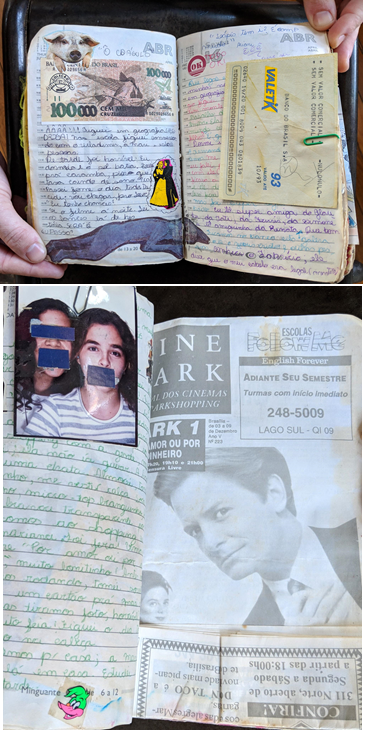

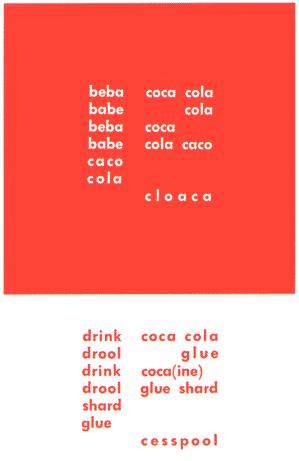

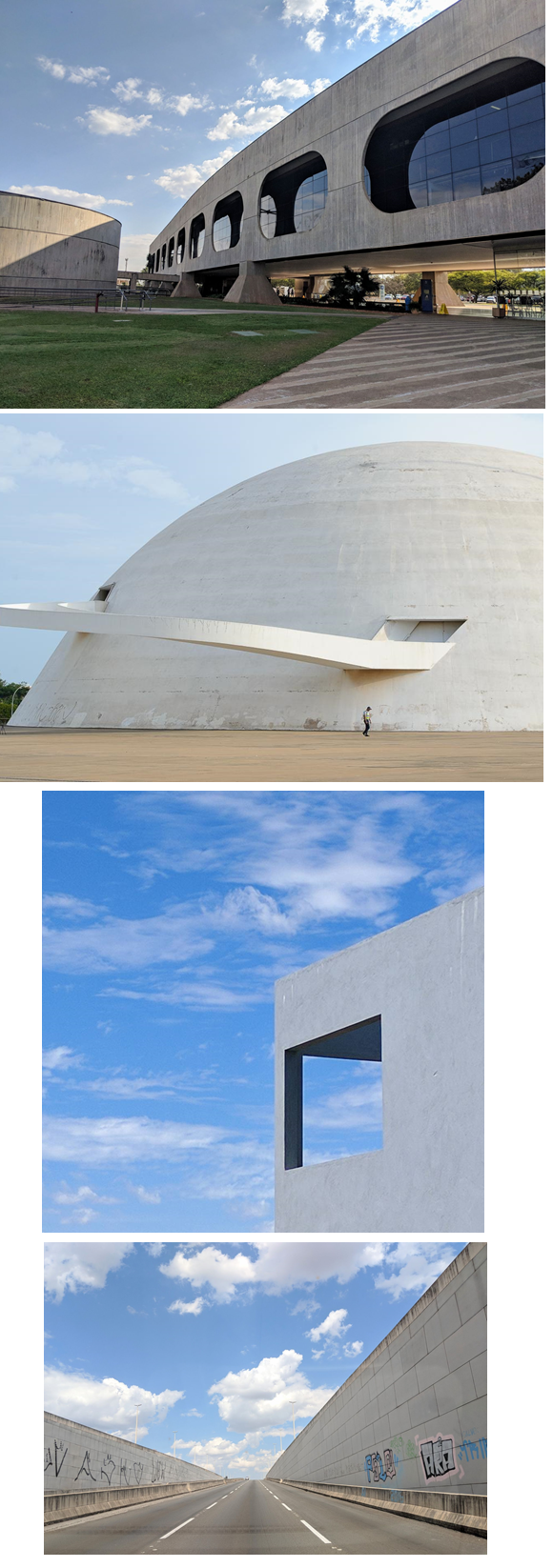

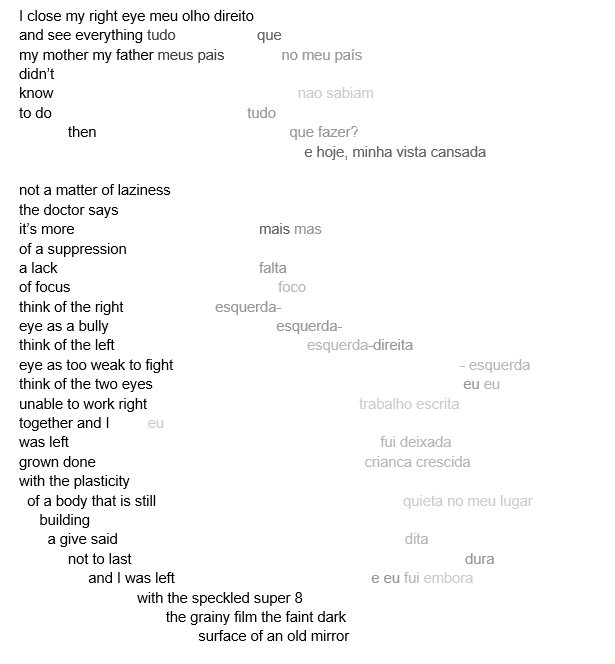

To be honest with my audiences, I am annoyed by these questions because the answer to the first question is always, "yes," and the answer to the second question is always, "Leaning a craft takes time". When I read Ananda Lima's essay, I understood why they asked me these questions. Creating new approaches to poetry (even though there are many historical examples, like Brazilian Concrete poetry) can be lonely. Finding a graphic & visual poetry tribe can be trying, as if you are cutting through a bamboo forest to find treasure. I again realize how important it is to connect with communities and share knowledge about graphic & visual poetry at the Working On Gallery. Some poets may just be apprehensive to step into unfamiliar territory. Now, if they ask me these questions, I say, "Yes. Come join us!" However, drawing & collaging art do not create a good graphic / visual poem. Borrowing Lima's word, "intuitive", is a part of the process - - you develop a feel for what works in your vision, your decisions are made with more confidence - - though, the intuitive ability comes after studying text poems. It is a long journey, but exciting. I found a new tribe member today. What am I doing here? Brief notes on being invited to hang out with graphic poets, and maybe line breaks By Ananda Lima As a poet, so much of the knowledge I have of my poems-in-progress or finished poems is intuitive. A knowing about whether something feels right, if it is doing what it should be doing, that is, ironically, apart from anything verbal. But a knowledge that is very much real. It might be only much later, often after the poem has been finished for a while, that a more verbal understanding might come. When asked to talk about a poem in an interview, discussing it with an editor, or talking to a friend, a verbal explanation might arise. An editor might wonder if a word should be shifted or cut, and only then, I develop a verbal understanding of why a specific word is part of the structure that holds what is underneath the poem, a structure that might not be entirely visible when skimming the verbal surface. Or a friend might make a connection that I had not expressed verbally, even to myself, but that I knew in some pre-verbal way was there. It's fun when I see those things come out in words. It can be illuminating. It can create new connections and generate new verbal or intuitive knowledge. It can make me feel understood. But it is always partial, tentative, not corresponding exactly to that non-verbal knowledge. This too can be satisfying/good news: if the poem can be paraphrased exactly, then it probably is not doing all it could do as a poem. A good poem, as a good story according to Flannery O’connor, should resist paraphrase. In a similar way, when Jennifer Sperry Steinorth asked me to join an event with a group of graphic poets and visual artists, including herself and Naoko Fujimoto, my membership in the group felt but intuitively right. This was despite the differences in the type of work members of the group were doing: there was brilliant and fascinating art that literalized and reinvented erasure while undoing a literal historical erasure, poems as transsensorial translation; a visual and sensory richness with mediums that included paint, white-out, lace, embroidery, and more, as well as words. Whereas I was had been keeping myself busy writing mostly good old regular text poems: (Though often these were poems where the visual played an important role.) Despite the contrast between the visual and medium complexity of the group and mine, I was only intimidated in the usual ways (ie, speaking alongside amazing people whose work you are very impressed by). But I did feel that I belonged with the group. Though I couldn’t initially verbalize why. In preparation for the event, I went searching for that verbal knowledge, trying to understand my feeling of belonging in the group. It wasn’t just that I was, separately, a photographer, as well as a poet. Or that I sometimes put photography and poetry together. It wasn’t just that I had been interested in the friction that words and visual objects create in the page for a long time. It wasn’t that as a child I was introduced to Brazilian Concrete poetry alongside sonnets and ballads and thought of them collectively as just regular poetry: (Or that somehow concrete poetry for me is emotionally entangled with concrete concrete, as in cement, the concrete of the Brazilian modernist architecture from the 1960s and today. Or that geometric, intentionally graphic or brutalist concrete structures around the world transport me to a time and place that only exists inside me, bringing me home. Or maybe all of that was part of it, but there was something else, more fundamental. I felt connected to the work of those graphic poets in a more abstract way, which is less dependent on a specific medium or specific biographical events. I started thinking about the poem I would discuss with the group, “Amblyopia”: Despite reading it out loud in different ways in the drafting process, when it came to reading the finished poem, I just knew what to do. Again, that knowledge was fully present, but purely intuitive. I read the solid left side of the poem out loud, as I would any poem. But I only read the first two lines or so on the right side, letting the rest fade away into silence. That way of reading felt very right. It was both part of how the poem was saying what it wanted to say and what the poem was saying. And seeing that how and that what intertwined is what I want to see in a poem. As it often happens when thinking about poetry, all of this lead me to to line breaks, a fundamental feature of poetry (maybe even prose poems, in their opposition to the line). The line break is an additional meaning making element which interacts significantly and meaningfully with the verbal, but is not itself verbal. It can be combined to reinforce or be in tension with verbal language, a wrestling for breath between break and syntax. Somehow the line break and that intuition about how to read “Amblyopia,” more than those explicitly visual art factors I mentioned before, were at the heart of why I felt I belonged with that group of graphic poems. Something about how the sound and the visual presence of text in the page sometimes reinforced each other, sometimes were in tension with each other and created meaning from their interaction. In graphic poetry, there is often a verbal component, words that have a stronger intrinsical link to sound, that can be read verbally without appeal for description. And there is the visual and/or tactile component, which “speaks” non-verbally. The poems are made of the two components working together to create something that cannot be simply replaced with description. In other words, graphic poetry is poetry. And it is poetry that makes that non-paraphrasable quality of poetry, fittingly, more visible. Verbalizing this, I am beginning to understand why graphic poetry, concrete poetry always felt to me, deliciously, a little meta, a little ars poetica, and very boldly poetry, even when the subject matter is not poetry or the poem itself. So the reason I felt I belonged there had less to do with the fact that I was also a visual artist, and much to do with the fact that I was simply a poet. A poet that cannot and does not always want to explain her poems. It had everything to do with that non-verbal factor that is essential to poetry, and a poem’s resistance to paraphrase. And there I felt right at home. Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land (Black Lawrence Press) is the winner of the Hudson Prize. She is also the author of two poetry chapbooks (Amblyopia, Bull City Press, and Translation, Paper Nautilus), a fiction chapbook (Tropicália, Newfound), and a poetry and photography chapbook (Vigil, Get Fresh Books). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark. You may also like reading:

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024