|

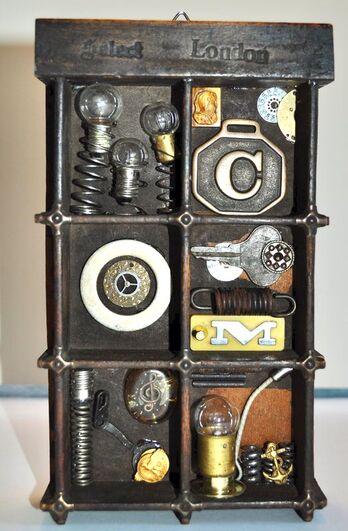

I have been thinking "What is Poetry?". There are so many creative diversities in the poetry field. Visual/graphic poetry is one of them. I think that there are more unique aspects, not only between written & visual elements, but also reading performances & exhibitions. For example, Joseph Cornell's boxes, Anselm Kiefer' concreates, and Renee Gladman's prose drawings have stronger visual aspects in their own poetic structures. Moreover, Douglas Kearney supports his poems with an energetic performance. I agree with RHINO editor, Daniel Suarez, when he said that "Poetry is an oral tradition", so performance is definitely a big part of poetic study. Today's guest, Nancy Botkin, was my first creative writing professor in my second semester as an exchange student. For every class, I had a new writing assignment from poetry, prose, fiction, and play, which was challenging, but really exciting because I could express myself while fellow students provided feedback. I was not a dead, quiet Japanese student in the class. She used "The Poet's Companion - A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry" as a textbook and focused on the chapter of image (she also talked about it more in the following craft essay). I remembered my first realization of "image" - - I was watching a movie, "Finding Neverland", with Thai students. Many dreamy scenes were shown in the movie. That's it! That meant image - - creative writing assignments became more stimulating once I learned how images affected my emotions. Now, she is becoming a poetic pack rat, collecting curious crumbs, gluing them in rectangles, and selling the collections. That is an amazing career after teaching poetry for twenty nine years. The Past Has a Future By Nancy Botkin There is a particular kind of person who loves the thrill of the hunt, loves to rummage through the old and discarded, and, for the sake of argument, we’ll call her an artist. A twisted piece of metal, a broken doll, a rusty wire, an odd-shaped piece of wood, and she says, “Is this salvageable? What will rise from these ashes?” Artists, I’ve learned, love what’s damaged and then go about remaking, reordering, or outright fixing, or by situating an object (or a word) in another context, they allow it to lean toward perfection. Making art is loving ruin and then honoring the wreckage. There’s nothing better than an old wood box that smells old. I close my eyes and begin to see the possibilities. Should it be stained, painted, or just wiped clean? And what will go inside this empty space? A poem, too, is at first a blank space. Clear a space, we say, when we want to begin something, open up our schedule, or before we set another plate at the table. I run my hand over white paper or turn a box on its side as if to anoint it with a special power. I have a plan for this, I say, but the plan remains open in order to protect mystery and accident. I close my eyes and begin to see the possibilities. For those of us who are lyric poets, the past is fertile territory. The proverbial she has a past, that we hear in fiction or film (often said in hushed tones), conjures up both romance and fear. Things, too, call up the past. Poets fire up the time machine and journey back to the house, the father, the woods, or that summer. “Remember those?” I hear people whisper at estate sales. “My grandfather had a pipe just like that” or “My mother used that same mixer!” Accustomed as we are to the products and conveniences of our time, the items of the past leave us in awe, breathless. Artists pluck them off the shelf, toss them into the present’s shopping cart, and roll them forward; the past always has a future. So, art makes the impermanent, permanent, or it freezes time—not exactly original ideas. Joseph Cornell, the originator of assemblage art, nourished his extravagant inner life by juxtaposing images (and vice versa) in his collages and box creations. Cornell loved ephemera and ordinary things, squirreling away postcards, lace, photostats, glasses, toys, and shells in marked boxes in his cramped basement. In a biography of Cornell, Deborah Solomon says “his objects offered a promise of immortality by virtue of their simple staying power” (48). We think of permanence after reading a well-known poem or when we view any notable work of art. What lasts is image, and perhaps a poet’s most useful tool is the image whereby the ordinary is imbued with significance. Nouns, I used to say to my creative writing students. Things. (“No ideas but in things,” Williams instructed.) Comb through your work and replace abstractions with the concrete, I would say over and over like a mantra. There’s a scene in the movie, Ordinary People, where Mary Tyler Moore squats down to retrieve a broken plate, and after surveying the damage, she says, “I can fix this.” Her world is crumbling around her, and she’s failing as a wife and mother, but she’s hoping the plate can be made whole. Perhaps my impulse toward art is a similar one. By shutting out a chaotic world where the “fix” will never be possible, I turn to art to assuage anxiety and to make myself whole. I sit in the chair or stand at the art table putting this here, moving that there, and taking that out. Rethink. Reorder. Remix. I look at my own basement and its clutter, a thousand objects stored away. I hold in my hand a glass bead or a metal key. I turn a word or a phrase over and over in my mind and I am rooted. Words and things move through me and extend beyond myself. Art is life’s elegant bypass; it weaves and circles around and back, returning me safely to the heart of it. NOTE Solomon, Deborah. Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell. London: Jonathan Cape, 1997. Nancy Botkin retired from Indiana University South Bend in 2019 where she taught first-year writing and creative writing for 29 years. Her latest full-length collection of poems, The Next Infinity, is available from Broadstone Books. Her assemblages can be viewed and purchased on Etsy (BoxesByNancy). Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024