|

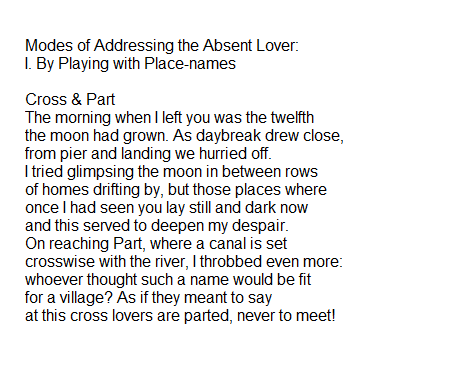

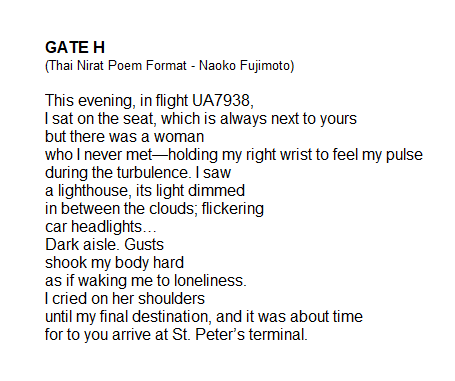

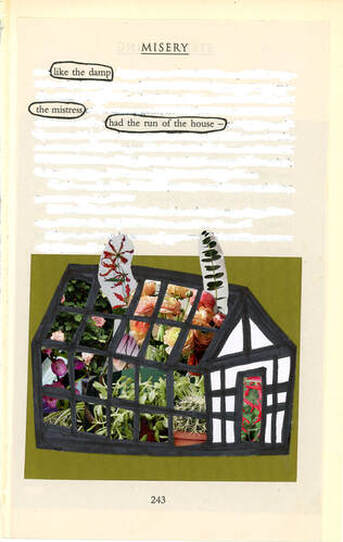

A while ago, Noh Anothai taught us how to write Thai Nirat Poems at the RHINO Poetry Forum. In his description of Thai Nirat Poems, the nirat is a sort of traditional Thai verse travel memoir (with origins as a courtly love poem): an account of journeys taken away from, and addressed to, absent lovers, that employs several conventions. One of his translation examples: “Cross & Part” reminded me of Semimaru’s waka. #10 Waka of Ogura Hyakunin Isshu (Anthology of 100 poems by 100 poets). Semimaru also known as Semimaro was a Japanese poet and musician of the early Heian period (around the 8th century). #10. (Translated by Naoko Fujimoto) Here, we meet we sprawl East to Kyoto to home once we pass this gate. Here. これやこの 行も帰るも 別れては 知るも知らぬも 逢坂の関 This waka is also playing with the name of the place. 逢坂の関 (Osaka no Seki) is a checkpoint for travelers to go down to Osaka or go up to Kyoto. Travelers must cross this gate. 逢坂の関 also phonetically means Au-saka no Seki, which is a meeting spot. Here is my Thai Nirat poem. Noh told us that Nirat poems can be gracefully corny. Support Working on GalleryYour $25 donation will be a tremendous support for Working on Gallery's future guests and running costs. If you become a patron, your name will appear in the next Working on Gallery's article. In addition, you will receive my first poetry book, "Where I Was Born", for U.S. shipments. Or, you will receive a thank-you letter for international shipments. Working on Gallery has been used by universities, advanced-level art lectures, and writing workshops. Your donation will help this gallery be more successful. Thank you so much - Naoko Fujimoto Sarah Sloat's newest book, Hotel Almighty (Sarabande Books, 2020), is a collection of poems after erasing words from the famous American psychological horror novel Misery by Stephen King, along with her visual interpretations. She explains her erasure poetry techniques in the following essay, as well as in an insightful interview by Kelcey Parker Ervick. Erasure poetry was introduced to me when I was in college. Professors and students in my poetry community were really into erasing words until I graduated. My professor, David Dodd Lee, was erasing John Ashbery’s poems for his book And Others, Vaguer Presences: A Book of Ashbery Erasure Poems (2016, BlazeVox). At the moment, I could not find joy in excavating new meanings from someone else's work. I felt it was more of a game than composing new poems, and I somehow felt bad for erasing words from the original text. However, my thoughts on it had changed since 2009. I learned of many erasure approaches, but had decided the most crucial decision lies in choosing the right material to work with. I met Alison Thumel who used The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Marie Kondo’s 2014 self-help best-seller. When I read her works, I truly understood the sparkling nature of erasure poetry. Sarah's book choice for Hotel Almighty was really intriguing. Her erasure poems carry the spirit of Misery through her personal lens showcased with collages. This is the technical and dramatic pinnacle of erasure poetry. By Sarah Sloat Hotel Almighty began four years ago as part of a month-long found poetry challenge. Every poet who put her hand up was assigned a Stephen King book as a source text, and mine was Misery. It wasn’t part of my usual reading terrain. There are many ways to approach found poetry. You can use words from all over the book, you can shuffle words from a single page, you can pick out all the questions in the book and compose a list poem, or pluck every sentence beginning with something such as “the snow” and go for anaphora. Or you can do blackout poetry, retaining the order of the words in the source text on a page or across a series of pages. I wanted to keep things simple, so I took this approach, limiting myself to one page per poem. This gave me freedom to start anew every day. Blackout poetry sometimes involves literally blacking out unwanted words with a sharpie. But the poet can also white them out, or blue them out with a colored pencil. Taking an eraser to the page also works to a certain extent depending on the ink and paper, but never fully obliterates the unwanted text. For a rough idea of how I approached the poems in Hotel Almighty, I’d like to discuss one piece from the book, [Like the damp…], which uses page 243 of Misery (Hodder & Stoughton). Each time I went looking for a poem, I resisted reading the text and instead looked at it as a kind of inventory. I gathered a basket of nouns and verbs and any interesting phrases. It was important to disengage from the story, which I did read prior to starting the project. On page 243, the phrase “like the damp” perches in the top line, impossible to overlook. As any poet can tell you, the simile is a mighty tool and a great temptation. “Like the damp” was a promising start, though I tried other possibilities. As with all the poems, I kept ideas in a notebook rather than marking up the page since I often changed course or abandoned a false start. I consider myself lucky with Misery. Stephen King likes solid nouns and verbs. His prose is lively, it’s peppered with good choices. Moving down the page, could one ask for a better word than “mistress?” It’s a powerful word that quickly arranged itself as the subject of the poem. At one point another version of this poem was at least twice as long. But in the end I kept it punchy, limiting the text to a single sentence: like the damp / the mistress / had the run of the house With every piece, only when I settled on a text did I consider the visuals. I wanted each poem to work on its own and obscured the superfluous text before choosing visual elements. For this poem, I used correction fluid. Parallel to working on page 243, I was doing collages with flowers, mostly stuffing structures with plants and blossoms. Because I couldn’t be bothered to keep finding new houses to pack with greenery, I drew my own primitive houses. I had two versions of this collage, the one used in the poem and another full of red roses, which seemed a bit monotonous. It’s a primitive rather slapdash drawing, like a child might do. Correction fluid, too, for all its charm is not the tidiest way to make an erasure. When I look at it now I think, wow, could have been a little neater than that! But it grew on me, as Misery did. Like the damp, like a mistress. Sarah J. Sloat splits her time between Frankfurt and Barcelona, where she works as a news editor. Her book of visual poetry, Hotel Almighty, was recently published by Sarabande Books. You can keep up with her at sarahjsloat.com and on Twitter at @SJSloat.

I was invited to an introduction to creative writing lecture at the University of St. Francis in Joliet, IL by Beth McDermott. She also talked about her creative writing and visual poetry materials in this interview. Due to Covid-19, I joined her zoom lecture with half of her students from their homes and the other half from the classroom. Despite the long distance, her students explored the concepts of graphic poems. We did a three-minute graphic poetry exercise with pens & pencils (black & white art). Their first drafts were stunning! After the exercise, we also had a short presentation of their graphic poems. The most fun and important part of creating graphic poems is deciding how to chose words and images from the original poem. Fundamentally, there are three choices:

I used Louise Glück's "All Hallows" for this exercise because:

Exercise:

All Hallows Each student selected different parts of Louise Glück's poem. Examples of the students' favorite lines are:

With these lines, they worked on creating their versions of graphic poems. They added visual elements - - some students drew styles similar to contemporary comics - - some explored Glück's meaning of "harvest" - - some connected and adapted their favorite movies or additional images into her poem. The amount of creativity they managed to conjure within three minutes was stunning! In addition, there was a good question about adapting the original into a graphic poem. One student asked how the graphic poet adapts the true meanings of the original poem. My answers were (so far):

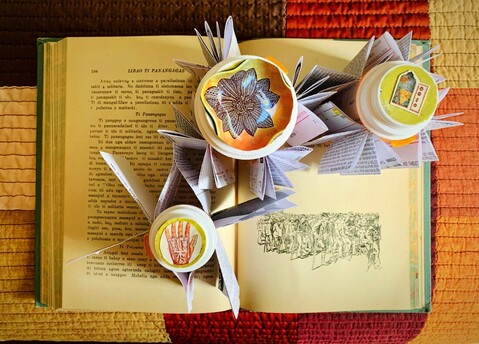

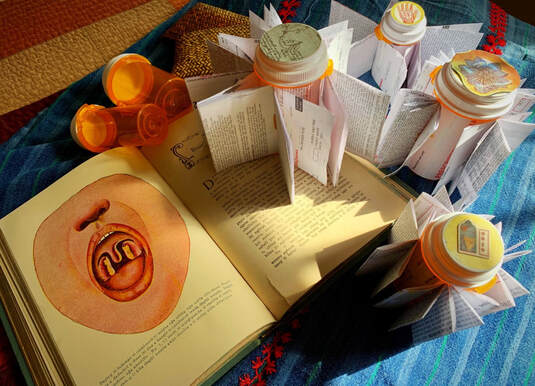

After I curated RHINO Poetry *graphic* Review, Luisa sent me one photo. Tiny pages were attached to a prescription bottle, which looked like it had flapping wings. The charming photo made me smile. Then, it slowly became grim - - in my imagination - - I could not stop thinking that the Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia was gluing pages on prescription bottles (in the kitchen?) after she was done with her medication. What did the pandemic do to her? Maybe, she & I were the same, craving & searching for creativity with ordinal materials. It was an amazing moment to realize that I personally got to know American Poet Laureates who shared their creative processes with me. In the past & forthcoming, Rodney Gomez wrote an essay about the process of his visual poetry book and Octavio Quintanilla will write an essay about his translation + visual poetry. I would like to cherish this fantastic highlight of 2020. It was a known fact that this year was tough on everybody in the world. But during this difficult time, poets found ways to push their minds and their craft forward, which was real encouraging. Luisa found creativity with ordinal objects and moved her hands to make something; perhaps, searching her zen-moments. I was fortunate to learn about her process. Pandora, Pandemya Luisa A. Igloria There are scenes in movies and TV series, in which a character goes to the bathroom-- to wash their face or brush their teeth, put on makeup, look for a razor, a cotton pad, a nail clipper. They pull back the hinged door of the wall-mounted bathroom cabinet, and there behind the mirror beside the object they were looking for, sit one or two amber-tinted plastic bottles. These are of course the ubiquitous amber prescription vials we all get from the drugstore, holding everything from headache medication to psychotropics to diuretics and Beta-blockers. Each has a printed label with your personalized dosing instructions, your physician’s name, and how many refills remain after you’ve completed that round of therapy. Each comes with at least 2 printed pages detailing drug facts, conditions and symptoms covered, possible side effects; plus little diagrams showing the shape of the pill or tablet: round, oval, triangular (there’s a migraine pill with that shape); scored. The thing I don’t quite get is how few of these bottles I’ve seen in narratives on film, despite the verisimilitude of everything else (in the same way perhaps that kitchens look far too neat to be lived in). My husband and I have about a dozen prescriptions between ourselves that we need to take daily. No way they would fit on those narrow white bathroom cabinet shelves. Besides, with the bathroom’s moist and humid environment (daily hot shower, anyone?) it really doesn’t seem the best place to store medication. Most of his sit in a small rectangular basket, and I have mine in a plastic tray I’ve recycled from some grocery item. We’ve also become those people who put their daily doses in dispenser boxes, each with a lid marked with the first letter of the day of the week. Every now and then someone repurposes one or two—safety pin container, spare button container, pill kit for travel (when we still could). Up until very recently, I’d tear or lift the labels off empties before putting them into recycling. I can’t even imagine how many of these we’ve used. We’re both past 55 (see how I did that coy little move so you don’t know where on the spectrum between 55 and 60 we are?), so we must have gone through hundreds. Out of curiosity, I did a bit of internet research and read that the global market in pharmaceutical packaging (including plastic and glass vials with tamper-resistant stoppers and caps) made at least $908 billion in 2017, with the North American market getting the largest slice of the pie. That is a lot of drugs. And a lot of vials. Sometime in late summer, in the middle of this pandemic, I started making and stab-binding handmade books using mostly recycled materials: stamped envelopes from letters that came in the mail, plastic bubble mailers, pancake mix boxes, a small stash of “Lucky Fish” fortune tellers that dropped out of the pages of a book as I was tidying up (I think they were giveaways from a poet’s book launch at an AWP conference years ago). I was preparing for a workshop I’m teaching for The Muse Writers Center in Norfolk starting 29 November— I’d given it a whimsical title: “The Poem is a Book is a Plane Ticket is a Chess Piece is a Lost Earring is the Clapper in a Little Bell is a Room Where You Can Breathe.” This is a themed workshop, but we’re also going to be adding a second layer of exploration to our writing in the form of visual elements. Perhaps the poets will embody their poems as postcards, cutouts, erasures, illustrated letters, accordion books, mini poetry zines, repurposed books, matchbox poems, and more. A sudden inspiration came out of nowhere: if a book is any number of pages (of different expression or make—paper, parchment, vellum, wood, stone, metal, etc.) meant to be written on, read, preserved, and placed inside some kind of cover, how could I turn a plastic pill container into a “book?” Perhaps it helped that I was also writing “sintomas|resetas,” a poem series revolving around the ideas of symptoms and prescriptions but expanding the “normative” meanings of both. In any case, soon I was gathering whatever prescription information sheets were still lying about the house; I either tore off or blacked out the parts with identifying information, then cut them into long strips whose width was more or less equivalent to the height of the prescription vial I would use to make my “book.” After a short process of trial and error fitting, I decided to stab-bind little books using the prescription sheets as pages. Then I glued them so front and back pages of each one overlapped all around the periphery of each bottle. I decoupaged the white lids of the vials to cover the tell-tale W logo of the drugstore chain, and also to continue in the process of transforming the object into something more than what it was to begin with. I’m mostly pleased with the results at this stage, though I think I will continue to manipulate each “book” some more—maybe I will paint images on the existing prescription pages using ink or watercolor or metallic marker. Maybe I will hot-glue a group of these “books” on a tray that will allow me to display them on a surface as well as hang them on the wall. Finally, I intend to deploy parts of my “sintomas|resetas” poems into each receptacle/book; perhaps I’ll include other objects (for instance, I have some Mexican milagros or folk charms a friend sent me a while ago) so that each “book” will literally hold both words and images/objects. Especially considering all the stresses we’re experiencing during this period of global concern over the pandemic, the economy, and the violence in our political environment, I don’t know that I’ll be “done” anytime soon with this project. As I work on these pieces, I keep thinking of the Greek myth of Pandora, and how she was created because the gods, forever jealous and territorial, couldn’t get over how Prometheus had stolen divine fire to give to humans. Pandora was supposedly the first mortal woman created by the gods; she was to be sort of their Enola Gay, as her purpose was to go into the world with a box of “gifts” which turned out not to be her dowry, but all the plagues and evils and diseases we now experience because these escaped when she lifted the lid out of curiosity. Hesiod describes Pandora in line 585 of the Theogony in pretty much misogynist terms: “For from her is the race of women and female kind: of her is the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth.” Pandora shut the lid in the nick of time though, so that one thing remained in the box—Hope. What about Pandemya (Tagalog/Filipino for “pandemic”)? She’s still loose in the world. Of course she will not be contained by politicians who willfully underestimate her, dismiss her as a trifle, something that we “just have to learn to live with” like the flu. In July 2020, Gov. Ralph Northam appointed Luisa A. Igloria as the Poet Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia (2020-22). Luisa is one of 2 Co-Winners of the 2019 Crab Orchard Poetry Prize for Maps for Migrants and Ghosts (Southern Illinois University Press, fall 2020). In 2015, she was the inaugural winner of the Resurgence Prize (UK), the world's first major award for ecopoetry, selected by former UK Poet Laureate Sir Andrew Motion, Alice Oswald, and Jo Shapcott. Former US Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey selected her chapbook What is Left of Wings, I Ask as the 2018 recipient of the Center for the Book Arts Letterpress Poetry Chapbook Prize. Other works include The Buddha Wonders if She is Having a Mid-Life Crisis (Phoenicia Publishing, Montreal, 2018), Ode to the Heart Smaller than a Pencil Eraser (2014 May Swenson Prize, Utah State University Press), and 12 other books.

Her poems are widely published or appearing in national and international anthologies, and print and online literary journals including Orion, Shenandoah, Indiana Review, Crab Orchard Review, Diode, Missouri Review, Rattle, Poetry East, Your Impossible Voice, Poetry, Shanghai Literary Review, Cha, Hotel Amerika, Spoon River Poetry Review, and others. With over 30 years of experience teaching literature and creative writing, Luisa also leads workshops at The Muse Writers Center in Norfolk (and serves on the Muse Board). She is a Louis I. Jaffe Professor and University Professor of English and Creative Writing— teaching in the MFA Creative Writing Program at Old Dominion University, which she directed from 2009-2015. For over nine years to date, she has been writing (at least) a poem a day. (Profile photo credits: Chuck Thomas, University Photographer, ODU) |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024