|

I met Dara at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. We were both visiting artists supported by Tupelo Press and staying at the museum residency area. It was one fantastic summer time - - exchanging creative thoughts and knowledge with other visiting writers and artists - - we also had a chance to visit Tupelo Press. Their office was located at an old factory building along with print makers, pottery studios, and many other creative spaces. Now, Tupelo Press' office is closer to the main building of MASS MoCA. During the stay, her poem was accepted by AGNI Magazine and we celebrated together. (She actually ate all my cooking, including super leftover spaghetti.) At that moment, she was working on her debut poetry collection, which won the 20th John Ciardi Prize for Poetry through BkMk Press at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Her book, DARK BRAID, will be available soon. On Creating an Animated Book Review By Dara Yen Elerath When Cynthia Cruz came to read at my MFA program--the Institute of American Indian Arts—I approached her to express how much I admired her writing. I’m shy and usually reluctant to speak to esteemed authors, but Cruz’s poems affected me and I felt compelled to voice my enthusiasm. Since then I have continued to admire the sinuous music of her language and her capacity to render experiences without moralizing, explaining or judging the characters in her poems. Instead of providing a framework for us to interpret her experiences, Cruz gives us a window onto them—dark and harrowing though they may be. At the beginning of her collection, The Glimmering Room, she cites the Gospel of Thomas: “If you bring forth what is within you, what is within you will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what is within you will destroy you.” In accordance with this, Cruz’s poems give voice to an inner world so dense and unexpected that it takes on the heady quality of a fever dream. The Glimmering Room addresses themes that might be too painful to encounter were they not wrapped in the narcotic beauty of her strange, raw and glamorously edgy imagery. It is this imagery I began with when considering how to create an animated review for her book. Many lines in her poems conjured visions of America in the 1990s. Specific items stood out to me: Paxil, Care Bears, My Little Ponies. These evocations of the 90s reminded me, also, of zines—small-circulation, self-published fan magazines common to the era. A do-it-yourself ethic was characteristic of these zines, which were often comprised of hand-made art and collaged images. While my own aesthetic is softer and does not reflect the punk sensibility of most zines, I still held them in mind as I began to lay out the graphic. The main figure in my design was inspired by the many girls, often depicted in treatment facilities, that populate Cruz’s book. The youthful trappings these girls bear—stuffed animals, glitter nail polish and skater-boy haircuts—make the incongruity of their already adult problems all the more poignant. In several poems they wear paper crowns, which serve as a particularly apt metaphor for the notions of false power that underlie the narrative threads in this collection. With regard to the animation, I wanted it to be minimal, but impactful. The review is composed of fragile, ephemeral-seeming elements—paper, tape, handwriting, line-drawings—that I hope reflect the psychic delicacy of Cruz’s characters; I decided that the viscerality of blood might provide a needed contrast to this. Since broken childhood is a defining theme of this collection I chose to animate the blood spilling from the girl’s chest like a gunshot wound. While the technical aspects of crafting this review are beyond the purview of this brief essay, I would like to mention that I used two professional design programs, Photoshop and After Effects, to composite and animate the review. The images I created were assembled in Photoshop then imported into After Effects where I generated the animations using tools in the program. I took a frame-by-frame animation approach with the blood, rendering out several states of the blood spilling downward and letting the program interpolate the states in-between these. I loved working on this graphic review, particularly for the time it gave me to spend contemplating the language and atmosphere of Cruz’s book. I appreciate the dialog between text and image, as well as between reader and writer, that these ekphrastic responses encourage. The idea of graphic book reviews is still new, but I’m grateful for Naoko’s work in generating the initial idea and in urging others to create them. My hope is that interest in these reviews-as-works-of-art will flourish and grow for years to come. Dara Yen Elerath is a poet and graphic artist. Her debut collection, Dark Braid, won the John Ciardi Prize for Poetry and is forthcoming in 2020 with BkMk Press. Virtual Girls Night with Dara at "ポエムスナックシャック" (Poem Snack-Shack)

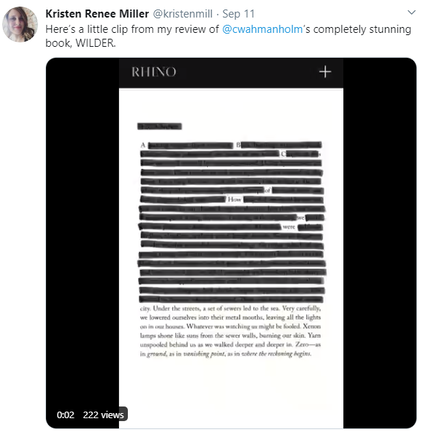

We were editing this article together - - she had a virtual glass of milk & I had a glass of water. I played the piano per her request. Have a drink with us. I met Kristen Renee Miller at a meeting of Third Coast Translators Collective. There Chicago-based translators gathered and exchanged their works through their discussions. I was invited to a corroboration workshop with the TCTC and RHINO Poetry. After the translation workshop, she showed me her art and I was stunned. All her works were original and yet relatable to current our society - - like the animated review from RHINO Poetry Review (Graphic Issue Vol.2). She used her creative technique to show her review message, "...A...B...C...of...How...we...were...wrong...wrong...wrong..." with erasure of poetry from the book, Wilder. Along with publishing her debut translation collection, SPAWN (Book*hug, 2020) by Ilnu Nation poet Marie-Andrée Gill, she writes poems, creates visual & animated art, & works as a managing editor at Sarabande Books. She is one of the most amazing and respected poets I have met. Reading Claire Wahmanholm’s Wilder in the Apocalypse By Kristen Renee Miller I first read Claire Wahmanholm’s book of apocalypse poems, Wilder, unforgettably, on March 11th, 2020, the same day the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. I was somewhere in the airspace between San Antonio and Louisville at the time—flying home from the conference for the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP), which controversially kept its annual event on the books despite an increasingly grim outlook, a public outcry, and vast dropouts from members, exhibitors, and attendees. For those of us who did attend, the conference maintained a furtive, conspiratorial feel in the hollowed-out convention center. Even at the height of conference hustle, it was impossible to shake the feeling of sneaking around someplace after hours, someplace abandoned, a modern ruin. The initial giddiness from superficial perks (room upgrades! no coffee lines! no wait for anything!) had long since dissolved into a heady sense of unease. In the previous days and weeks, we’d been conditioned to doubt the evidence of our own senses concerning the virus (are we in danger? are we imagining things?), an ambivalence for which AWP was a tidy play-within-the-play. Did exchanges in book fair aisles feel hushed because of some shared sense of transgression, or only because we weren’t shouting over fifteen-thousand other people? Was the lighting in the exhibitor hall dimmer this year, or were we imagining it? At night we gathered at hotel bars and toasted the event ironically, hubristically, as co-conspirators: Uncanny Valley AWP. Last-Chance Saloon AWP. Zombie Apocalypse AWP. Enter Wilder, which I borrowed on the plane from my seatmate and colleague Joanna and inhaled in a single leg of the flight. Wilder finds humankind mid-apocalypse in an imagined near future. In dreamy, gorgeous abecedarians, fabulist prose poems, and erasures of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, Wahmanholm describes a frighteningly plausible apocalypse. Yes, there is the environmental blight, the wildfires, the extinctions; yes, there is the ruin left by wars; there, the plagues ravaging those left. What leaves the strongest impression is the complete bewilderment of those who remain to witness it all, the chorus, the book’s collective “we.” “Which of our wrong things had been wrong enough?” asks the collective voice in Wilder—the same question we conference goers and non-goers were asking ourselves and each other (mostly on Twitter) in early March: Which of our individual choices are responsible for this? Which of our collective choices? And what of the visible and invisible move-makers completely outside our control? Embedded in every exchange was the same shared sense of doom, the inevitability of The Worst. Already we had become Wilder’s chorus. My animated review, which can be viewed in RHINO Reviews issue 3.3, is my attempt to encapsulate in just a few lines Wilder’s dreamy dread and Wahmanholm’s inventiveness and exquisite craft. Starting with Wahmanholm’s abecedarian “Beginning” as a source text, I created a seven-part erasure poem* that unravels and rewrites itself as it careens (a little too fast) toward an inevitable “vanishing.” My previous visual poems have been individual images or image series, meant to allow the eye to linger, to wander. In this animated piece, however, I wanted to hurry the eye ahead at a pace a little faster than is comfortable to recreate my experience reading Wilder in the apocalypse: that slippery sense of the bottom dropping out, that hypervigilance that makes you afraid to blink. *** *For those interested in the technical stuff, I made the animation using the Markup editor on my iPhone. I recorded the video with the iOS Screen Recorder and edited it with the mobile app Vixer. I’m sure there are far more professional tools for this sort of project, but I liked the slight imperfections of my method and the tactility of swiping the lines out one-by-one with my finger. Kristen Renee Miller’s work appears in POETRY, The Kenyon Review, Guernica, The Offing, and Best New Poets 2018. She is the translator of SPAWN (2020), by Ilnu Nation poet Marie-Andrée Gill. A recipient of fellowships and awards from The Kennedy Center, the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, and the American Literary Translators Association, she lives in Louisville, Kentucky, where she is the managing editor for Sarabande.

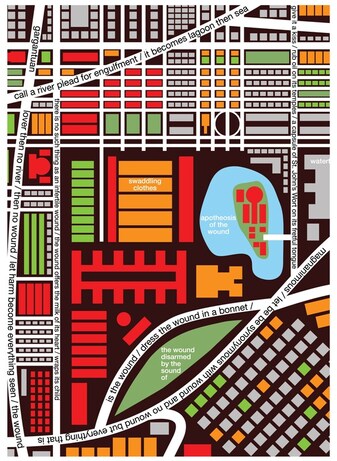

Gomez's visual poetry book will be out soon this October from Pleiades Press. This press accepts visual poetry collections. Their submission guidelines are on their website. It is really fantastic to see that they publish all interpretations of visual poetry. When I read Gomez's book, I immediately thought that he beautifully dissects his poems—each phrase deforms into image & word—like a cell dividing into multiples and creating new life. These fragments become a solid block, like a new identity throughout his book. It was really amazing to observe his works. Then, I become curious about how he creates his visual poems. His work is digitally processed (unlike my graphic poems), but there are still earthly vibes in his poems. When I obsess over something or someone, I cannot resist learning from them. Gomez kindly replied to my question, "How do you process your visual poetry collection?" Rodney Gomez: Geographic Tongue began as a series of black & white word-only poems. Most of my visual poems start out that way. But sometimes you work a poem and put it aside wanting to return to it with fresh eyes. What happened is that a lot of these pieces mutated in hibernation. They demanded images, colors, lines, and shapes. It became quickly apparent that I was wasting my time attempting to pigeonhole them into monochrome. The more I gave up traditional text the easier it became to discover the true body of each piece. Some poems no longer needed a transition—they emerged fully formed as their true, colorful, dynamic selves. Now almost every poem I write has a visual twin. It has become easy to identify what form the poem needs and deserves. At the same time I was writing Geographic Tongue I was also writing the poems in another collection, Arsenal with Praise Song, which arrives in January 2021 from Orison Books. That book confronts very violent imagery, mutilation, death, and similar themes, but there are no visuals in it. Perhaps Geographic Tongue is respite to that work. Not that it lacks involvement with some tough themes. But there is something gentle and conciliatory in color and shape. Everything the reader sees in Geographic Tongue is a result of discovery. Visual poetry is a new thing for me and so the collection shows efforts of newness. There are few collages here, few poetry comics. Nothing was painted or drawn with my hands. Everything was constructed in virtual space, and with a mouse, although I dislike using ‘virtual’ because the digital space is just as real as the space we take breath in. My guiding principle was aleatory: to give the poem whatever body it needed. The result is a mix of different textures and tones. Rodney Gomez is the author of Citizens of the Mausoleum (Sundress, 2018), Ceremony of Sand (YesYes, 2019) and Arsenal with Praise Song (Orison, 2020). His work appears in Poetry, Poetry Northwest, The Gettysburg Review, Blackbird, North American Review, Pleaides, Denver Quarterly, Verse Daily, and other journals. He is a member of the Macondo Writers’ Workshop. In 2020 he will serve as the Poet Laureate of the city of McAllen, Texas. Picture credits from The Indianapolis Review

The following essay was inspired by Hyejung Kook's zuihitsu 随筆 sentence. The original exercise was about 10 minutes, and in the RHINO Poetry Forum, all poets shared their lines from 5-second paragraphs of the 10-minute exercise. You may try this exercise even though I am a trained professional, you can still try this at home. "A Cat Sits On a Mat"

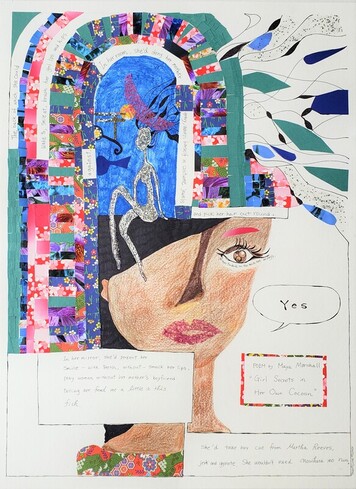

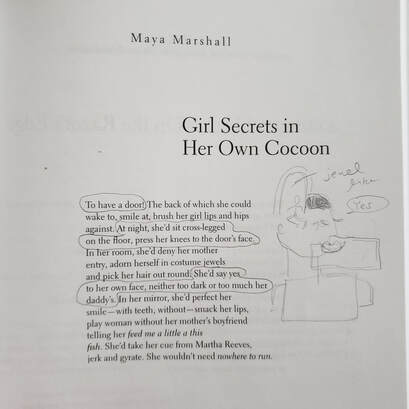

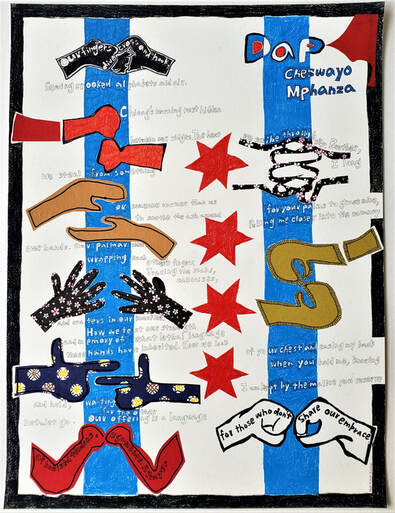

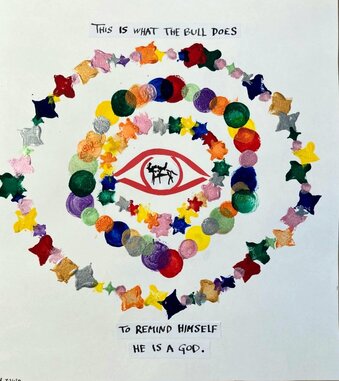

This is the first sentence ever I wrote in English. Probably, I wrote it more than one hundred times. My first English teacher was introduced by my sister’s kindergarten friend from East Asia (I do not remember where his family came from) and his mother taught us English twice a week in our cookie-cutter apartment in Japan. A cat sits on a mat. It was British English--I noticed it later when I started my exchange student life in Indiana--so my sister and I learned British English pronunciation, but shortly after, our new English teacher came from Australia. My pronunciation is somewhere between Japanese—British—Australian—American Mid-west, but I realized my spelling of the color, “grey”, is in British English. In her class, we first practiced the pronunciation of ABC as /ə/ /b/ /k/. We drew, “a cat sits on a mat” in our notebooks. Usually my sister took longer than I did. Soon, I started decorating the cat and mat. My first cat had a bow tie with a new cat wearing a silk hat. There was a flower vase on the mat. It is clearly no longer, “a cat sits on a mat”. I drew food—chopsticks, bowls, and tea cups. I added furniture around the cat (and more cats). Eventually I designed a whole house for the original cat that sat on the first mat. Some colorful cats lied on the floor. A blue cat sits on a mat. Adding the word "blue" was the most exciting moment I still remember. My brain recognized connecting words with meanings. Despite not memorizing how to spell, I could say many colors and objects in English before she went back to her own country. A cat sits on a mat. In our first class, my nephew and nieces were repeating the same sentence with their crooked handwriting, but my nephew was quiet. He did not want to say the sentence nor draw it. "I don't understand your gibberish", he despaired, crying. His eyes wide open and raw like a small animal gnawing. He left our dining table and went to the corner, holding his paper. A cat sits on a mat. A cat sits on a chair. A cat sits on a table. "Is it bad manners?" my nieces laughed in Japanese, so I laughed too. After the class, they kept drawing and adding things around the original cat like I did nearly thirty years ago. My nephew came back and slammed his paper on the table, showing a gigantic purple cat sitting on the tiniest green mat. Then, they started chasing each other. This is a part of some graphic poetry workshops I recently held. I would like to share three examples of how we can approach and start creating a graphic poem. Once you start creating one, you will flow and feel sparks in your brain! RHINO Poetry recruited about ten poets to highlight poems by our poets of color: poems of love, courage, anger, jubilation, and resistance with graphics until September 9, 2020. You may see the project through our Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. The following graphic poems are from the project. The assignments are to read and understand RHINO Poetry's published poems, then add graphics. There are several ways to approach this. Today’s quick exercise is to create a first sketch graphic version of your poem. (We will show it later during our workshop.) Example 1 Process: #1) Decide which words become images or remain words. Maya Marshall's original poem is attached. The circled parts were translated graphically. #2) Create collage. Example 2 Process: #1) All words are on the paper. #2) Images are also added. Poem: "Dap" by Cheswayo Mphanza. Example 3 Process: #1) Select the most vivid/heated phrase(s). #2) Add images. Poem: "Bull's Eye" by Luisa Igloria, Poet Laureate of VA. Graphics by Chloe Martinez & her daughter, Amina. You may enjoy reading my past articles about "How Graphic Poetry Helps Us Progress the Story Telling Technique and the Creative Process of Its Own Editing".

How do I choose materials and color schemes? One simple way to improve observing habits after graphic poetry exercise Is it difficult to have divergent thinking? Can a graphic poem have a line break? Why didn’t I write down whole poem in a graphic poem? My editing technique has developed after a collection of graphic poems |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024