|

I translate:

They are two types of translations; however, the both are utilized by Steven & Maja Teref mentioned in their craft essay. [A]s translators, it is our job to move the “data” and “information” of the source text to help the reader make sense or gain “knowledge” about a text, and we hope that by anchoring the music of the text in fixed English syntax, we have generated a blueprint for the reader to understand and enjoy it. That beautifully explains what translators do with their works. For my two translation works:

The translators build a bridge from the original written text to the readers who may live in a different time & place. Steven & Maja Teref have been perfecting their translation method together as a married couple. They translate from Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian to English. It is a bit north of Croatia, but it was in Czechia that Kelcey Parker Ervick found inspiration for her book. It is a biographical collage (mixed with texts, footnotes, fragments, and images) entitled "The Bitter Life of Božena Němcová: A Biographical Collage". In today's craft essays, there are some original languages, and they remind me of texts from Parker Ervick's book. She also joined the graphic poetry audio exhibition. Craft Essays by Collaborated Artists in the Working On Gallery: Gail Goepfert x Patrice Boyer Claeys

Onetime, I asked Steven & Maja Teref how they find words? They immediately said, "Like when we do dishes?" I remembered that I thought about how romantic it is to search for one exact word after dinner, doing dishes, and wiping off plates together. It was just an envious moment for artists who have each other to achieve the same goal; in addition, the chores are also done. Two birds with one stone! I could image them working together, as if on an assembly line - - dirty plates into soapy water, brush, rinse, & wipe with a dried towel (with yellow & dark green flower prints of course) - - in smooth motions, they found a particular word for their particular poetic line. So, I would like to ask you today to read the following craft essay while imaging them at their dining table. Dust in the Sunlight: Translating Light by Steven Teref and Maja Teref Literary translation is the seeking of a text’s light. The more difficult the text, the more difficult to see its light. Imagine a sunshaft through a skylight window, the soft heat stirring the air. In the updraft, dust motes clot the light. Imagine this dustlight as the difficult parts of a text. The more difficult the text, the more backscatter. To translate a text is to translate its light. Each writer we choose to translate comes with challenges, but our end goal remains the same: the reader has to see the writer. The most difficult writer by far for us has been our latest project: translating MID (pronounced “mead”), the nom de guerre of Mita Dimitrijević, the most enigmatic character of a group of 1920s Yugoslav avant-gardists who referred to themselves as zenithists. He is such an obscure figure that when Belgrade, Serbia recently mounted an exhibition this year in celebration of the hundred-year anniversary of the short-lived movement, MID’s presence was conspicuously absent. MID would seem to be the backscatter of zenithism. For context, zenithism was a unique literary and art movement in the crowded field of 1920s avant-garde Europe on numerous fronts because it was a cross-genre movement on two levels: it synthesized the various separate avant-garde tendencies into one aesthetic, and it embraced hybrid writing as a central tenet of its poetics. From the word-packed panels (like action-packed film frames) of Ljubomir Micić’s Your Hundred Gods Be Damned to the Dada-leaps of Marijan Mikac’s poetry in Effect on Defect to the cinematic jump-cut landscape of Yvan Goll’s long poem Paris Burns to the tragi-comic expressionist-proto-surrealist novel of Poljanski’s 77 Suicides, each zenithist scattered the light. And then there is MID. MID was so ahead of his time that his time is yet to come. His omission at the zenithism retrospective this year confirms it. MID published two books with the zenithists: The Sexual Equilibrium of Money (1925) and The Metaphysics of Nothing (1926) before seeming to drop off the face of the earth. We have translated the former, a work as innovative in 2021 as it was when first published. What makes MID so difficult to translate, what makes his work so buried in dustmurk is the density of his metaphoric language and the allusions worming through his work. Yes, his work flips from prose to verse and from Dada to surrealism, but that’s child’s play for him. For a text punctuated, at times, by nearly empty pages, Sexual Equilibrium of Money is a dense work. Its alternation of word-bursting pages and ellipsis-strafed pages makes the work a dynamic feast as much for the eyes as for the mind. On its surface, it seems as if each page follows its own set of rules independent of the other pages. Is the work fiction? Poetry? A philosophical treatise? A collage? Found text? Is it even about money? Yes, all of the above. It is as much about economics as it is about Yugoslav identity, European politics, Kantian philosophy, the opposing natures of God and Jesus, the nature of nothing. Added to the mix were editorial errors such as cited text missing closing quotation marks. This isn’t to say that the book doesn’t have structure. The book is formally split between the verso and recto pages. The unnumbered verso pages generally repeat the word “KEY,” but the word degrades as the book progresses. The recto pages, their page count in descending order, can very loosely be chunked into four sections:

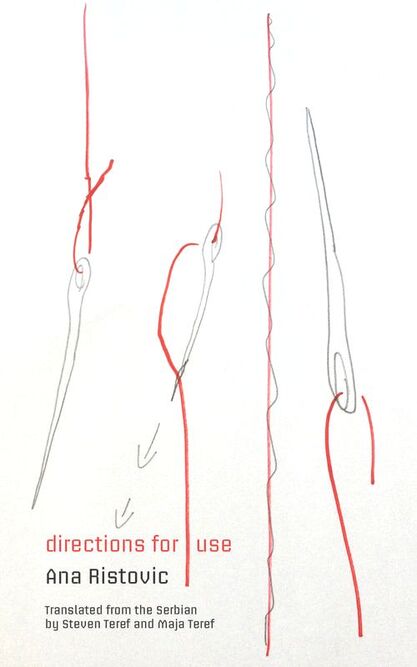

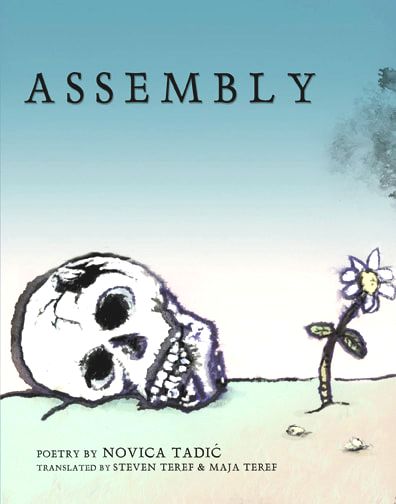

This is not a well-established theorized structure, since there has yet to be much literary criticism on MID, but this helped us understand how to approach MID’s esoteric text. The allusions are more times than not uncited or intentionally mis-cited. For instance, MID inserts a German translation of Hamlet’s famous line, “To be, or not to be” and attributes it to Schopenhauer! It must be noted that the verso pages begin with the declaration: “STEAL FREELY!” MID did this with aplomb. For all of the seemingly random quotes and concepts, the book is anchored in numerous refrains, such as Kant’s “thing-in-itself” and the word nothing. We workshopped an excerpt of an early draft of our translation at a Third Coast Translators Collective workshop (TCTC), but our fellow translators were daunted and perplexed by what we thought was a comprehensible first draft. Despite our best efforts at the time, all they saw were the “dust motes” or what Toni Morrison would call “data” and “information,” but the reading of the text for them remained largely hindered by the lack of rhythm and structure of the English language. The feedback was insightful and unanimous—keep the strangeness, the oddity, but the connective tissue needs to be familiar; keep the Hegelian/Kantian diction but adhere to English syntax. We were still far from Laurence Perrine’s “cone of light” or the ability to have the reader cull some knowledge from the text. Not surprisingly, since Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian has a developed case system, it has an incredibly flexible word order, something that English, with its sparse case system, doesn’t have, which accounts for its dependency on fixed word order. To help the reader see what we saw meant that we needed to tame the word order and expand the “cone of light” so that the light can contain or encompass the dust motes within its shaft. To backtrack a little to elucidate our process, doing the “trot” (or “gloss”) of MID’s text, felt more like taming a wild horse, or translating the first, literal draft. Although this project was not our first rodeo, translating MID seemed impossible at first: tackling a hybrid text which reads like prose poetry written in finance jargon with Hegelian and Kantian reasoning and sentence structure, printed on invoice banking paper with pagination in descending order and with the refrain of difficult-to-translate, opposites, necessitated, first and foremost, a slow, close-reading and, more than anything else, thorough reading comprehension. As we hacked and combed through the text, we often thought of Toni Morrison’s essay “Unspeakable Things Unspoken” in which she cautions us all to be aware of the progression of understanding from data to information to knowledge to wisdom. We felt at times palpably stuck on data interpretation of recurring opposites, namely the pairing in the phrase lice i naličje, so much so that Morrison’s information stage didn’t even seem in the offing. In our pursuit of clarity and light, the genealogy of lice (face, front, obverse) and naličje (back, reverse) took us from “reverse and obverse,” and “heads and tails” to “front and back,” “face and back,” “outside in and inside out,” “overt and covert,” “seen and unseen,” “visible and invisible,” or “recto and verso,” but through this journey, we began to gain some knowledge on how to think about his dust-thick work by trying to live in MID’s head. It became clear MID was satirizing the deceptively balanced yet hopelessly elusive, unjust Kafkaesque world of finance. The absurdity of his refrains started to sing for us, and we began to laugh with him. Yes, he was playing with the reader, much like a master Dadaist, but there was a logic underpinning his argument, as arcane as it was, so we also had to follow his clues. One allusive sentence in particular stood out: “Arius of Alexandria preached that the first perfect creation was dead matter (+), a ‘thing-in-itself:’ a WORD created from NOTHING: an eternal, self-important, UNCREATED divinity (–).” Up to the TCTC workshop, we had been only able to see the dust and not the light of the text. But for all of MID’s dust, he leaves hints of light. The dichotomy is not the front and back of a bill but the dual nature of nothing. Arius argued that Jesus had a distinct corporeal beginning and end that could be seen—he came from nothing and was therefore not eternal. Whereas God, without beginning and without end, cannot be seen and is eternal. This idea of being seen or not seen, coupled with numerous quotes with the word nothing, seemed central to understanding the work as a whole. The Sexual Equilibrium of Money is not a religious treatise, but the religious conceit serves as one of many conceits driving MID’s exploration on the nature of currency. In fact, the book, like its companion, is an early example of conceptual writing. If there was a single key to unlocking the cryptic secrets of Sexual Equilibrium, this sentence seemed as likely a candidate. If nothing else, it allowed us to find a way to make sense of the recurring references to “thing-in-itself” and “nothing” in relation to lice i naličje. As a result, we eventually landed on the “seen and unseen” as perhaps the best solution. Part of what makes translating MID so difficult is that there has yet to be extensive scholarship on his work. Working with Columbia University scholar Aleksandar Bošković, we’ve been able to decode many of MID’s allusions and make sense of his logic, and as a result, untangle his syntax into recognizable English-language sentence structures. The Sexual Equilibrium of Money will appear in the forthcoming Zenithism (1921–1927): A Yugoslav Avant-Garde Anthology on Academic Studies Press in 2022. To return, once again, to Morrison’s essay which we have applied to translation, as translators, it is our job to move the “data” and “information” of the source text to help the reader make sense or gain “knowledge” about a text, and we hope that by anchoring the music of the text in fixed English syntax, we have generated a blueprint for the reader to understand and enjoy it. And as for Morrison’s explanation of “wisdom,” it is our hope that our reader’s experience of MID’s text will better illuminate the world around them having read this translation. Maja Teref and Steven Teref translate from Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian. Their books include Novica Tadić's Assembly and Ana Ristović's Directions for Use, the latter of which was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award, Best Translated Book Award, and the National Translation Award.

Maja is a past president of Illinois TESOL. She teaches English at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools where she is also the faculty advisor for Ouroboros Review, a student-run literary translation journal. Steven's other books include Foreign Object, Pleasure Objects Teaser, and The Authentic Counterfeit. He is currently coediting with Aleksandar Bošković Zenithism: A Yugoslav Avant-Garde Anthology (1921–1927) (Academic Studies Press, 2022). Some people have never done collaborated works. When I watched reality TV shows like Project Runway, candidates sometimes did not get along in their group projects. So did some writing classes that I took in the past. Do collaborated projects give us a headache? Often, we as artists are so focus on our individual achievements that we cling to what we've already established. I've done it. But through the experience, I think that only individual success means less than we think in the long run. Our individual creativity shines when we have multiple unique creations around us. If our community is boring, our own art might be boring too. Through 2020 and 2021, I witnessed multiple collaborative works between poetry & art. I asked about their creative processes, and one thing that I noticed was that they were light as a feather, in contrast to unsuccessful collaborations feeling heavy and incoherent. Craft Essays by Collaborated Artists in the Working On Gallery: Gail Goepfert x Patrice Boyer Claeys

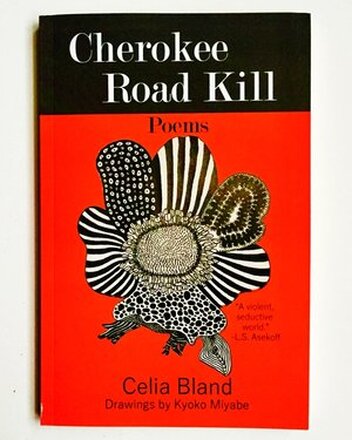

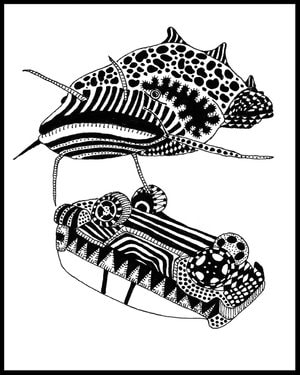

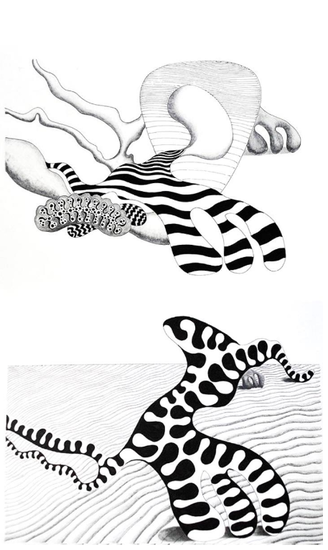

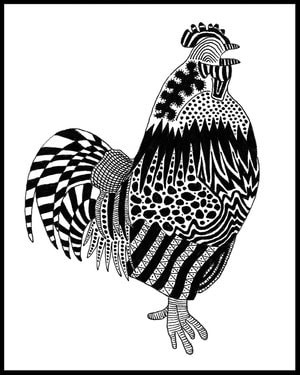

The successful collaborative works were rigid as a whole presentation, and I could feel trust and respect from the final products. It is so hard to find the best match for a collaborated work. But how exciting it is when you find a great teammate in your creative process! Today's guests, Celia Bland & Kyoko Miyabe, intermingled their creative approaches when they collaborated on Cherokee Road Kill & one broadside together. In the following video, I read "Brave" from Cherokee Road Kill. Bland kindly gifted me a signed copy. Thank you so much. I actually wanted to read "Trail of Tears", but my website did not have the capacity for a long record. It is a 6 page-poem, each page has a paired drawing on the side. I think that the poem truly highlighted both a collaboration of Bland's words and Miyabe's images. If you are interested in seeing the beautiful work, find out! Sight itself is a picture. By Celia Bland My mother is an artist and even now, in her 80s, she paints every day. When she runs out of blank canvases, she begins painting over paintings. For her, the act, the practice, matters more than any objectified goal. Watching my mother as she opens her birthday presents -- the way she feels of the silky ribbon, lifts the deep pink of the birthday card to her face as if she would taste its color, smooths the wrapping to absorb texture and even sound through her finger tips – it’s almost too private to watch such a sensual dialogue with the world. Growing up with someone who creates beautiful things has made me greedy for beauty. My most recent poems, which take the form of scripts for a TV series about Andrew Jackson and the Seminole leader, Osceola, were spawned by memories of my childhood in Florida where my mother was an art professor. Shut-in, cut off, here in the Hudson Valley of New York, since March, I was reading about Mar-a-Lago and the pro-Trump regattas, about the absurd, tragic response of the Florida governor to Covid-19 and the death tallies, and I began thinking about the Seminole Wars that resulted from a very Florida-style land grab in the 1830s. President Andrew Jackson’s (illegal) proclamation that the Seminoles be “removed” from their lands in central Florida to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi, followed the removal of the Cherokee from the Carolinas and Georgia (an event underlying and influencing the poems in my last collection, Cherokee Road Kill). I was also remembering the three-dimensional “feel” of Florida. Black Palmetto roaches as big as your palms. Thunderstorms. The wind whipping moss-bedecked trees and spined palmettos until they tossed and twisted like grieving women. The sand that scalded your feet, and yet was cool and damp immediately beneath the sun-blistered surface. And the people who sat telling stories on themselves – their mistakes and foolishness, the world’s ridiculousness. Failure. That's what I wanted to write about. But not in the first-person. Almost as a listener who laughs wryly, bitterly. “Shooting Script: Brazen Jackson, Season One, Ep. 1-13” was the result. Kyoko, who collaborated with me on Cherokee Road Kill (Dr. Cicero Books), was kind enough to create drawings that could accompany these poems. Her work, like her conversation, is hyper-articulate. What she expresses in these drawings, as it relates to my poetry, is a parallel force: "The force that through the green fuse drives the flower," to quote Dylan Thomas. What she draws (literally?) from the poetry is not the action of the poem but the impetus of the poem. I find a correlative in Robert Rauschenberg’s work with Merce Cunningham. Rauschenberg related less to Cunningham’s choreography than to the revolutionary energy – the curving, tensile, spiraling propulsion -- he brought to dance. The yes’s and no’s as decisions are made each literal minute of music, noise, movement, and language. Rauschenberg’s backdrops, props, and costumes complicate and complement these aesthetic decisions. You see thinking in their work together. I find in Kyoko’s clarity of line the singular hand of an artist who creates life in her drawings. The evidence of decisions – so many! so infinitesimal! – is in every directive of the line. The slight bleed of ink on fine grained paper is heartbreaking. Her work leaps away from Phillip Guston’s organic shapes, infusing them with femininity. Rather than the heavy boots, factory chimneys, and hooded figures of his canvases, we find epidermal layers taking on the curling force of pistils, hairs, and sockets. Here is the dynamism of curving lines, resting and interdependent. Hairy tendrils of stem, sharp-bladed leaves, curves of hip and knuckle, bumper and mushroom cap. I recognize the thrusts and torques of poetic lines. Here is the anarchic “Shooting Script” -- its gallows humor, cultural naming, bitter vitality, critique, and tragedy. All of which will, I hope, prompt readers to ask: when the mediums are so different, the images so different, the languages of the lines so different -- what could possibly connect poem with image, image with poem? What are we seeing? What ideas are incited, provoked, and solicited here? You got me. Between Kyoko’s work and my own I find a frictive conversation. A sly enticement to look and listen. Our collaboration takes the form of a reiterative question that remains stubbornly and tearfully open to all comers. In closing, allow me to mention that our most recent collaboration is a broadside of new images and poetry published by Green Kill Gallery in Kingston, NY. If anyone would be interested in a pdf of the broadside, please write to: 229greenkill {at} greenkill.org. By Kyoko Miyabe When Celia approached me about a project to create drawings for her latest poems, I was excited about being able to collaborate with her again. What soon dawned on me though was that this project entailed a new approach. For Cherokee Road Kill, I selected some of the poems’ detailed elements that stood out to me -- such as a rooster, a green skirt, and “a whiskery catfish god” -- and created drawings of them. The images grew out of my vicarious engagement with the landscape and the inhabitants of the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina as recounted by the speakers in Celia’s poems. Perhaps this engagement was similar to how we become involved with places and characters in books, sometimes to the point where they can seem as real as, if not more real than, our immediate world, no matter how distant or unfamiliar they may actually be. Plus, while I did not know Louise -- to whom Cherokee Road Kill, I felt at the time, was ultimately dedicated -- I might have thought that I could maybe be permitted to take part in this elegy as another woman, as another private individual. However, this time with “Shooting Script: Brazen Jackson, Season One, Ep. 1-13,” I recognized the need not only to learn more about the poems’ main figure, Osceola, but also to find a way to approach their larger, more public, historical subject -- one that I felt I did not, and therefore could not be allowed to, share in as someone from a different heritage. The last paragraph in Jonathan Blunk's excellent review of Cherokee Road Kill (The Georgia Review, Summer 2018) offers an insight into this subject, and what is at the core of Celia’s poetry: Bland’s stubborn honesty reminds me of D. H. Lawrence and an essay of his that first appeared nearly a century ago, “The Spirit of Place.” Lawrence argues for the “great reality” of this idea that everywhere on earth has a distinctive and enduring spirit of place. Writing about America and its literature, Lawrence doubts whether we as a people can overcome the legacy of slavery and the genocide of native inhabitants driven from their homelands. This fundamental savagery—and the uncertainty we face as a country—are present throughout Cherokee Road Kill. By honoring a community blighted by this inheritance, Bland has given us a lyrical portrait of a neglected but essential American place. Celia’s latest poems address this "fundamental savagery" underlying the history of the United States in a manner that encapsulates the textures of American culture, both in its enduring and contemporary form. The entry point I was seeking emerged when I read Patricia Riles Wickman’s Osceola’s Legacy (The University of Alabama Press, 2006). In the preface to the revised edition of this book, Wickman writes: To be sure, a main objective of my researches since the initial publication of the book has been to gain a fuller understanding of the cultural, social, and historical context of the man and to locate his missing head. This latter aspect of his story has a high cultural and spiritual value to the Seminole people, and especially the Florida Seminoles, with whom I lived and worked for all the years that the first edition of this book was in publication. It is, consequently, they who have my deepest appreciation for their willingness to share of themselves and of their rich and fascinating universe. It is their belief that the spirit of a deceased person passes out of the physical body through the head in order to make its journey westward, across the Milky Way, to the realm of all the spirits. If the head does not remain connected to the corpus, therefore, the confused spirit may remain too close to the living and can become malevolent, at worst, or a wanderer, at least. (p.xiv) This paragraph immediately made me think of Noh drama, which often retells stories of ghostly spirits unable to completely leave this world because of strong lingering emotions, whether it be sorrow, rage, regret or resentment. I then thought of the image of the old pine tree painted on the back panel of the Noh stage. This image became the starting point for the set of drawings accompanying “Shooting Script: Brazen Jackson, Season One, Ep. 1-13.” These drawings do not directly engage with, but rather, exist in parallel to Celia’s poems. Like the painted old pine tree standing at the back of the Noh stage, they bear witness to the retelling of a tragedy that embodies the “enduring spirit of place.” Celia Bland’s third collection of poetry, Cherokee Road Kill (Dr. Cicero), featured drawings by Kyoko Miyabe. Recent work has appeared in Plume, Witness, Copper Nickel, Southern Humanities Review, and the anthology Native Voices: Indigenous American Poets (Tupelo Press). With Martha Collins she co-edited Jane Cooper: A Radiance of Attention (University of Michigan). Kyoko Miyabe received her Ph.D. in English Literature at Cambridge University, U.K. She is the Chair of the Humanities and Science Department at School of Visual Arts, New York. As a practicing artist, she has exhibited in galleries and art institutions in New York and Philadelphia, including Woodmere Art Museum, Jeffrey Leder Gallery, Stevenson Library at Bard College, New York Hall of Science, and Philomathean Society Gallery at University of Pennsylvania. A selection of her pen-and-ink drawings was published in Celia Bland’s collection of poetry, Cherokee Road Kill (Dr. Cicero Books, 2018). Along with Mariko Aratani, she is the co-translator of By the Shore of Lake Michigan, ed. Nancy Matsumoto (UCLA Asian American Studies Press, forthcoming), a book of tanka poetry by Tomiko and Ryokuyō Matsumoto.

A good friend of my mother's gave me a gift, which was a porcelain decoration with a lot of flowers. Her note said, "It reminded me of you when you were a little girl." Since March 2020, I have been decorating and drawing flowers more often. Flowers have the power to heal when I feel like a burden. More from WORKING ON Gallery: |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024