|

Poets are hard trainers (Period)

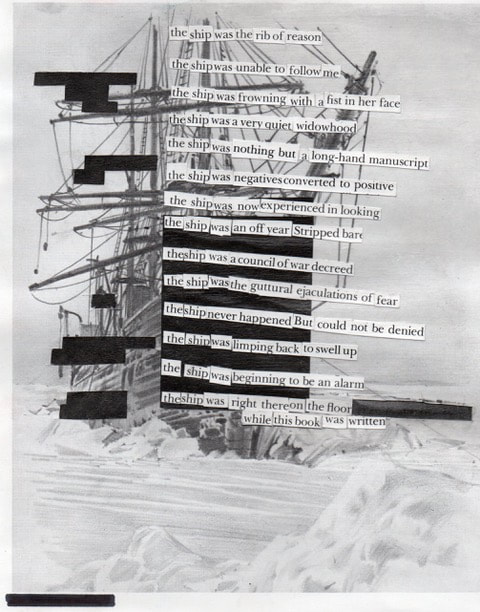

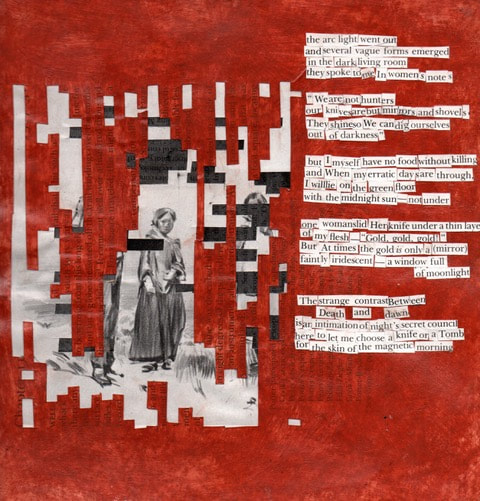

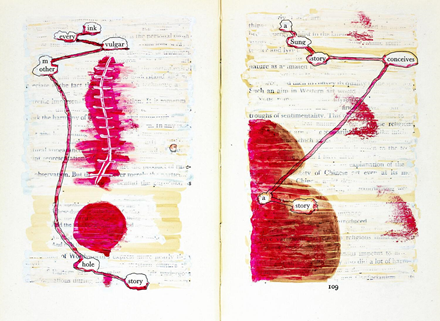

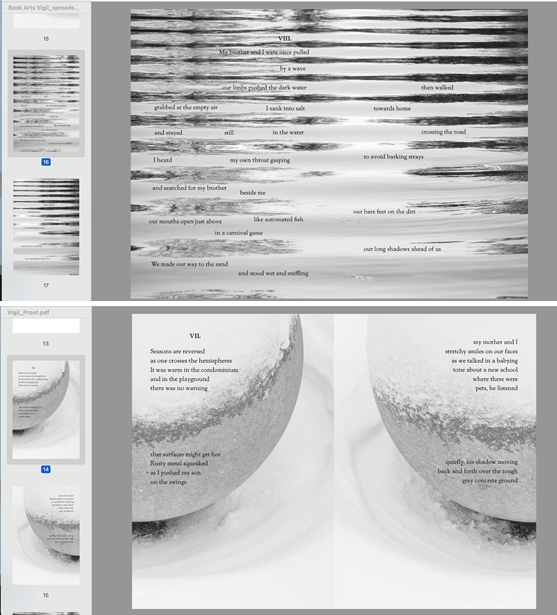

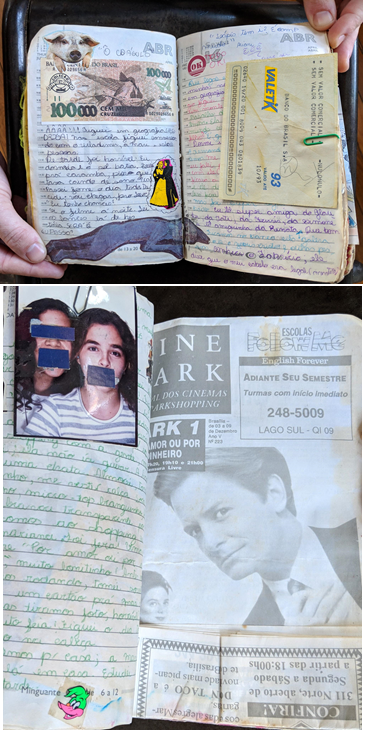

It can be more relatable to observe athletes at the 2021 Tokyo Olympic & Paralympic Games; instead, poets are, perhaps, like Auguste Rodin's The Thinker. Poets reach the limit of ones capacity - - write, erase, re-organize, destroy, create again, and then the final product - - though the products may not be well received by audiences. They may be overlooked or invisible. I do not think that it is an ideal environment for our creative selves, it is one that may lead to self-doubt and wrong impressions about our creations. However, the process is part of poetic progress. In other words, we - - poets - - have to find the optimal balance between our perception of our work and its reception. Ina Cariño, Kylie Gellatly, & Mary Ruefle (her essay is shared by Gellatly later in this article) have similar sutras for this. I think I’ve finally made peace with the fact that things take time, and that time takes time, too. - - Cariño You haven’t even begun. You must pause first, the way one must always pause before a great endeavor, if only to take a good breath. - - Ruefle When I reviewed Gellatly's book at RHINO Reviews, I was immediately curious as to why she adapted found poetry with art, and why she chose that original source, The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter. I was not expecting such vivid details. The Fever Poems by Kylie Gellatly The Fever Poems is the result of a myriad of circumstances; including but not limited to a head injury, a bad case of hives, the (then new) Covid-19, and a big move. I am tedious when telling the story behind this book, as it feels romantic in a way that I feel timid taking credit for. Maybe that is the nature of found poetry. Trying to tell the story of how this book happened is like trying to scoop a pile of shapeless things, or oozy goo blobs, into my arms and then try to carry them some distance and make an eloquent hand-off. What shape would you give to a head injury, hives, the pandemic, lockdown, packing up an apartment, the protests, isolation, the feeling that all I have is everything I have and is everything I will lose. How to contain this: The Fever Poems was a towel to clean up a spill, or a vessel—the kind of vessel that a towel becomes when it is entirely saturated. I had been working on a collection of poems and had just discovered the through-line, that the poems were about grief of self, or past selves. Then came the breath, the pause, the prescription: no screens, rest your brain, your eyes. Then, a physical enactment of the grief that I had recognized, under the circumstance of not knowing whether I would be able to restore my brain function to what it was before. The head trauma I was recovering from was one that had, at first, subtly hindered my ability to comprehend what I was reading, but under pressure, led to trouble with comprehension in both reading and writing. I was prescribed a month of rest and given strict parameters around what my brain could handle. I mostly just wrote letters to keep in touch and found so much creativity in this communication, which asked for something to be made in order for it to be said. I was drawing and collaging and writing a lot of letters, long letters, to various people; carrying on these disjointed conversations over gaps of time and distance. I think of Mary Ruefle’s essay “Pause”, in which she says, “You must pause first, the way one must always pause before a great endeavor, if only to take a good breath.” The choice to use The Arctic Diary of Russell Williams Porter started with reason and turned into another. At first, it was simply that I was preparing for a move, cleaning out my books, and questioning whether I would take this book to another new place with me. My collection of arctic literature had once been very enthusiastic but, by this time, Porter’s diary was the only one left. I had carried it around for years for sentimental reasons and for a very dear inscription inside. I thought, it can only come with me if I make it into something else. So I tore out the inscription and started pulling the book apart. My obsession with arctic literature was an antidote for a steady depression and had presented itself to me as a form of escape that bred optimism toward endurance, stamina, and unlivable conditions. The nature of this use became poignantly clear to me as the nature of its escapism and toxic kind of endurance pointed at a lot of the shame I had been carrying. The book became a symbol for a fixed narrative, something I had been keeping my fragmented selves inside of, on ice. In retrospect, the best way I can think of the creation of The Fever Poems is as a month-long play in which I enacted an homage to the grief I was holding inside me for every person I had been in my life and a deconstruction of the walls that I held around each of them. Instead of leaving a pile of rubble, these collage poems are mosaics, made in a fit of compassion, that create a myth all its own, starring a fluid “we” and “I” — sourced from the context of Porter either speaking for himself or on behalf of his crew — to meld into a single, whole, and present form. Creating one poem every day for a month suspended judgement, doubt, and question long enough for a trust in myself and my voice to grow. Kylie Gellatly is a visual poet and the author of The Fever Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2021). Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in DIAGRAM, Tupelo Quarterly, Iterant Magazine, GASHER, Literary North, Palette Poetry, and elsewhere. Kylie is the Book Reviews Editor for Green Mountains Review, Editor-in-Chief of Mount Holyoke Review, and is a Frances Perkins Scholar at Mount Holyoke College.

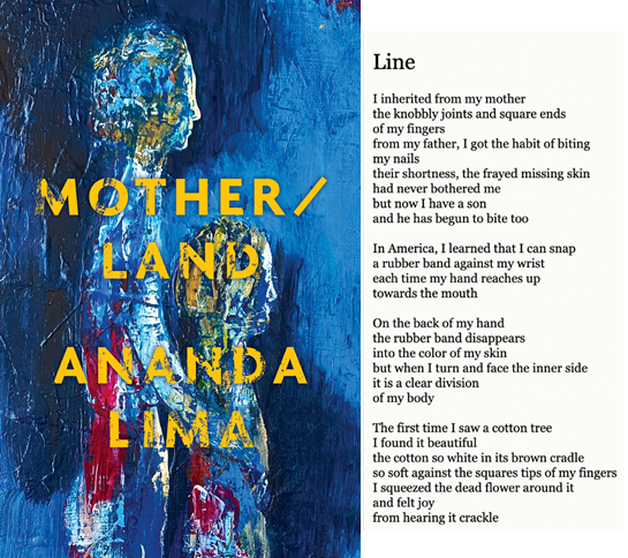

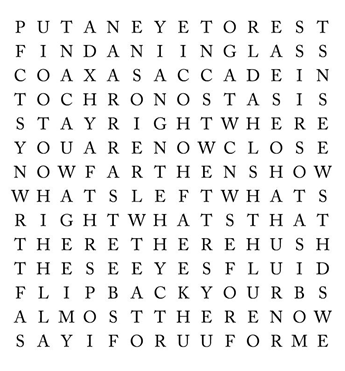

I often receive two questions:

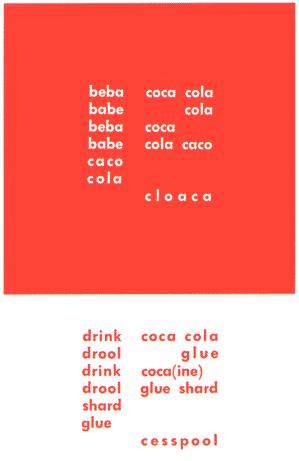

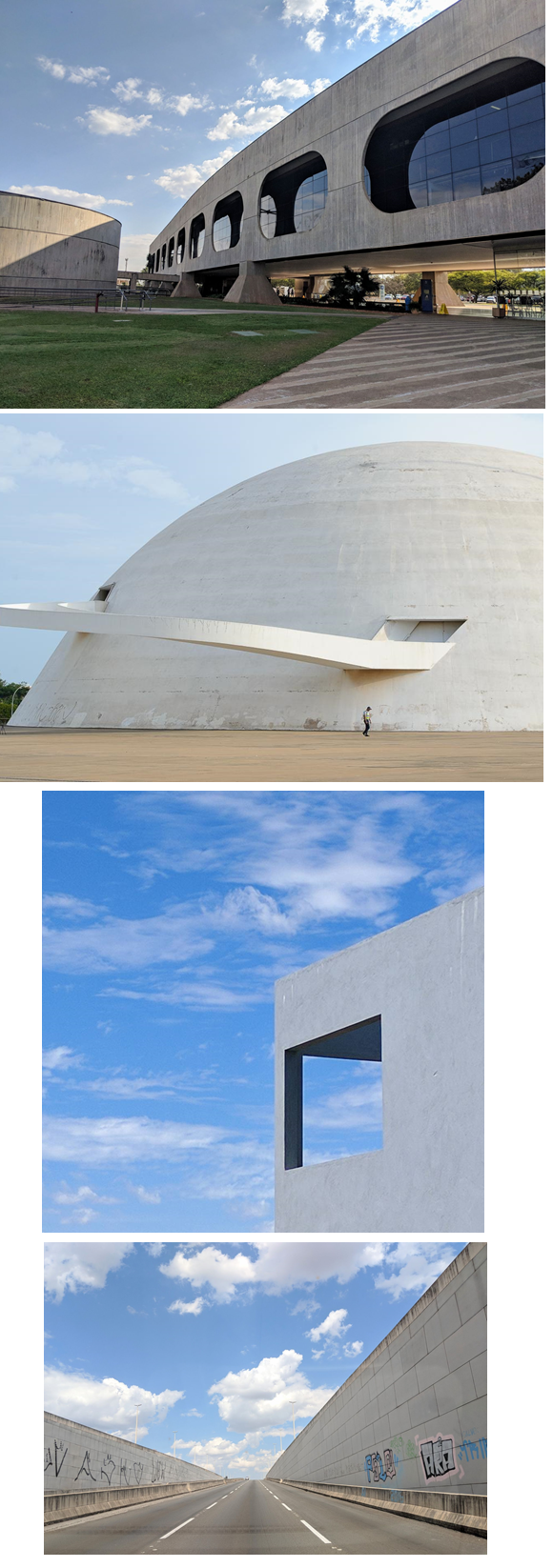

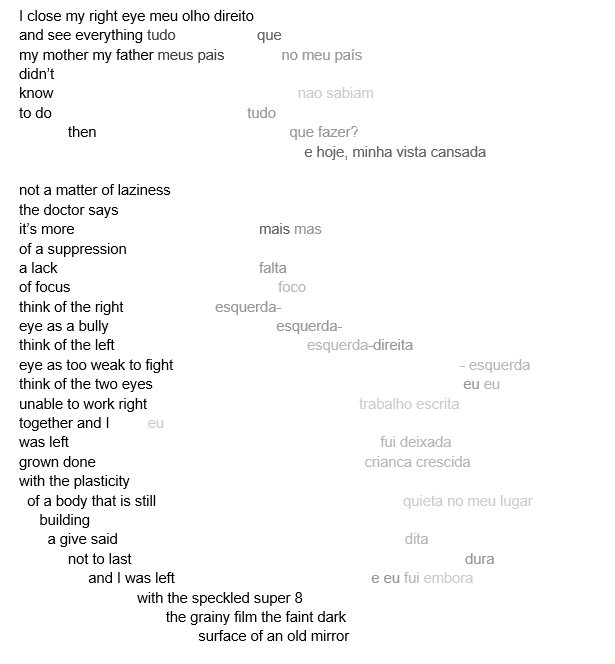

To be honest with my audiences, I am annoyed by these questions because the answer to the first question is always, "yes," and the answer to the second question is always, "Leaning a craft takes time". When I read Ananda Lima's essay, I understood why they asked me these questions. Creating new approaches to poetry (even though there are many historical examples, like Brazilian Concrete poetry) can be lonely. Finding a graphic & visual poetry tribe can be trying, as if you are cutting through a bamboo forest to find treasure. I again realize how important it is to connect with communities and share knowledge about graphic & visual poetry at the Working On Gallery. Some poets may just be apprehensive to step into unfamiliar territory. Now, if they ask me these questions, I say, "Yes. Come join us!" However, drawing & collaging art do not create a good graphic / visual poem. Borrowing Lima's word, "intuitive", is a part of the process - - you develop a feel for what works in your vision, your decisions are made with more confidence - - though, the intuitive ability comes after studying text poems. It is a long journey, but exciting. I found a new tribe member today. What am I doing here? Brief notes on being invited to hang out with graphic poets, and maybe line breaks By Ananda Lima As a poet, so much of the knowledge I have of my poems-in-progress or finished poems is intuitive. A knowing about whether something feels right, if it is doing what it should be doing, that is, ironically, apart from anything verbal. But a knowledge that is very much real. It might be only much later, often after the poem has been finished for a while, that a more verbal understanding might come. When asked to talk about a poem in an interview, discussing it with an editor, or talking to a friend, a verbal explanation might arise. An editor might wonder if a word should be shifted or cut, and only then, I develop a verbal understanding of why a specific word is part of the structure that holds what is underneath the poem, a structure that might not be entirely visible when skimming the verbal surface. Or a friend might make a connection that I had not expressed verbally, even to myself, but that I knew in some pre-verbal way was there. It's fun when I see those things come out in words. It can be illuminating. It can create new connections and generate new verbal or intuitive knowledge. It can make me feel understood. But it is always partial, tentative, not corresponding exactly to that non-verbal knowledge. This too can be satisfying/good news: if the poem can be paraphrased exactly, then it probably is not doing all it could do as a poem. A good poem, as a good story according to Flannery O’connor, should resist paraphrase. In a similar way, when Jennifer Sperry Steinorth asked me to join an event with a group of graphic poets and visual artists, including herself and Naoko Fujimoto, my membership in the group felt but intuitively right. This was despite the differences in the type of work members of the group were doing: there was brilliant and fascinating art that literalized and reinvented erasure while undoing a literal historical erasure, poems as transsensorial translation; a visual and sensory richness with mediums that included paint, white-out, lace, embroidery, and more, as well as words. Whereas I was had been keeping myself busy writing mostly good old regular text poems: (Though often these were poems where the visual played an important role.) Despite the contrast between the visual and medium complexity of the group and mine, I was only intimidated in the usual ways (ie, speaking alongside amazing people whose work you are very impressed by). But I did feel that I belonged with the group. Though I couldn’t initially verbalize why. In preparation for the event, I went searching for that verbal knowledge, trying to understand my feeling of belonging in the group. It wasn’t just that I was, separately, a photographer, as well as a poet. Or that I sometimes put photography and poetry together. It wasn’t just that I had been interested in the friction that words and visual objects create in the page for a long time. It wasn’t that as a child I was introduced to Brazilian Concrete poetry alongside sonnets and ballads and thought of them collectively as just regular poetry: (Or that somehow concrete poetry for me is emotionally entangled with concrete concrete, as in cement, the concrete of the Brazilian modernist architecture from the 1960s and today. Or that geometric, intentionally graphic or brutalist concrete structures around the world transport me to a time and place that only exists inside me, bringing me home. Or maybe all of that was part of it, but there was something else, more fundamental. I felt connected to the work of those graphic poets in a more abstract way, which is less dependent on a specific medium or specific biographical events. I started thinking about the poem I would discuss with the group, “Amblyopia”: Despite reading it out loud in different ways in the drafting process, when it came to reading the finished poem, I just knew what to do. Again, that knowledge was fully present, but purely intuitive. I read the solid left side of the poem out loud, as I would any poem. But I only read the first two lines or so on the right side, letting the rest fade away into silence. That way of reading felt very right. It was both part of how the poem was saying what it wanted to say and what the poem was saying. And seeing that how and that what intertwined is what I want to see in a poem. As it often happens when thinking about poetry, all of this lead me to to line breaks, a fundamental feature of poetry (maybe even prose poems, in their opposition to the line). The line break is an additional meaning making element which interacts significantly and meaningfully with the verbal, but is not itself verbal. It can be combined to reinforce or be in tension with verbal language, a wrestling for breath between break and syntax. Somehow the line break and that intuition about how to read “Amblyopia,” more than those explicitly visual art factors I mentioned before, were at the heart of why I felt I belonged with that group of graphic poems. Something about how the sound and the visual presence of text in the page sometimes reinforced each other, sometimes were in tension with each other and created meaning from their interaction. In graphic poetry, there is often a verbal component, words that have a stronger intrinsical link to sound, that can be read verbally without appeal for description. And there is the visual and/or tactile component, which “speaks” non-verbally. The poems are made of the two components working together to create something that cannot be simply replaced with description. In other words, graphic poetry is poetry. And it is poetry that makes that non-paraphrasable quality of poetry, fittingly, more visible. Verbalizing this, I am beginning to understand why graphic poetry, concrete poetry always felt to me, deliciously, a little meta, a little ars poetica, and very boldly poetry, even when the subject matter is not poetry or the poem itself. So the reason I felt I belonged there had less to do with the fact that I was also a visual artist, and much to do with the fact that I was simply a poet. A poet that cannot and does not always want to explain her poems. It had everything to do with that non-verbal factor that is essential to poetry, and a poem’s resistance to paraphrase. And there I felt right at home. Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land (Black Lawrence Press) is the winner of the Hudson Prize. She is also the author of two poetry chapbooks (Amblyopia, Bull City Press, and Translation, Paper Nautilus), a fiction chapbook (Tropicália, Newfound), and a poetry and photography chapbook (Vigil, Get Fresh Books). Her work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, and elsewhere. She has an MA in Linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in Creative Writing in Fiction from Rutgers University, Newark. You may also like reading:

I am so pleased to present Lea Graham's craft essay about her translation process for my anniversary month. The Working On Gallery turned one year old, and there is no better way to celebrate it than with her astonishing biographical essay. I had goosebumps the whole time reading it. This is why I started the gallery. This gallery is personal in the sense that it allows authors to share their creative processes, some created from years of intimate self discovery, culminating in the choices that define dreams and careers. Graham is a translator who currently works with a Chilean poet, Sergio Coddou. I translate Japanese waka-poems because I am seeking threads of my heritage through ancient words - - the use of language, images, and sounds - - If I study these poems, I feel the spaces between between my body (where I physically exist) and soul (where I belong) fill out. For me, waka-poems build my creative identity. My roaming soul (to borrowing some of Graham's translated words) is still out there. Time seems to crawl when I try to articulate what it seeks, or why it roams. But when the moment is right, it is beautifully answered. As if Coddou's wife said, “That word… it has a little bit of soil in it.” It Has a Little Bit of Soil in It: Reflections on Translation & Place By Lea Graham Translation is intimate work. As with any significant relationship, there’s risk and routine. There’s something secretive about it too, as if you, the translator, have discovered what no one else has before. I often feel that I’m falling into the poem as I’m translating. The intensity of investigation into individual words, phrases or idioms; the searching into word histories, and the exploration of the poet’s life and concerns creates a familiarity, a camaraderie, an empathy. Like any intimacy, it slows the world down. When I first started translating poetry I was in graduate school in Chicago, living in the largely Spanish-speaking neighborhood of Pilsen on the Near West Side. The details of the living room in the apartment I worked from are vividly recalled: the honey-brown Mission-style desk (scored in a fancy North Side yard sale), a large red hibiscus flowering in one of the tall windows and a honey locust peering in from another. Both looked out onto 21st Place and Damen where I lived for nearly a decade and where later in the day I would hear the jingle of the elote man’s cart and then, the ice cream truck’s “Turkey in the Straw” as evening slipped into night. The ceilings were high, giving the room a sense of amplitude; various Spanish, English and etymological dictionaries lay in a half-moon around my computer and on the floor around my feet. Each morning two crows valentined each other—one from the roof of the house across the street, the other up in the tree. It took me a few weeks to realize that as I worked, they were having their daily coffee klatch. My first project those years ago was in translating poems by the Chilean poet, Gabriela Mistral. My professor, upon learning that I was working in Spanish, said “Oh, you must translate Mistral.” She said it with such conviction but also in a tone that suggested I would continue to be the undereducated rube she thought I already was if I didn’t. What I learned from her that semester was the kind of teacher I did not want to become. Each class she made caustic remarks about all we didn’t know or would pointedly ask one of the older and more fluent graduate students to read our work out loud, not so subtly implying that she couldn’t bear to hear our pronunciation. Still, the lessons and experience of translating Mistral more than made up for the condescension. Gabriela Mistral was a poet and an educator who championed the rights of women, children and the poor before becoming a diplomat for Chile. She was a fierce advocate of democracy and education in her own country and throughout Latin America which is why so many schools still bear her name. All this appealed to me. I had spent a few years living in Spanish-speaking communities where, in one of my jobs, I worked as an advocate for Central American refugees. Weekly, I drove my clients to the Immigration Office in Paterson, New Jersey, stood in line, petty-bribing the guards with sticks of gum, a smile, and my whiteness, trying to get my clients moved up further in line. I still remember the negotiation process when we finally got to the counter: there I was in my ripped-at-the-knee-jeans, just out of undergraduate and my first time in the Northeast; my clients, mostly young or middle-aged Salvadoran or Nicaraguan men, all silent and anxious next to me. I could feel both their fear and faith as we negotiated their green cards in an exchange that was almost always rude and sometimes blatantly hostile. We always managed to get it done. Afterwards, I could feel the relief in their more relaxed postures as they insisted upon taking me to lunch at the nearby Salvadoran restaurant. That was where they would tell me details of their families back in San Salvador, Santa Ana, Managua or Esquipulas—of blackouts and nightly curfews, of the missing and the not knowing, of the last phone call they had with their mother, their brother, a niece. Those moments across a table where we shared plates of pupusas de queso y revuelta, tables covered in red and white plastic coverings, a picture of El Salvador up on the mostly bare wall, the low hum of conversation and small clatter back in the kitchen. Despite these experiences and my philosophical connection to Mistral’s life’s work, I had never been to Chile. I had no sense of the breath-catching rise of the Cerro del Plomo from the streets of Santiago, the endemic flora that appears in her work—plants that couldn’t travel elsewhere because of the specific and confining terrain, or the Gainsboro to Spanish grays and Egyptian to azurite blues of the ocean off the Valparaiso coast that now, years and travels later, remain as some of the most mysterious and dreamy seascapes of my life. What I did understand was her loss of place and the identity that went with it. Mistral’s losses—both that of her lover and a beloved nephew by suicide, along with her name change from Lucila Godoy Alcayaga to her pseudonym (drawn from the names of two favorite poets; the Italian, Gabriele D’Annunzio and the Provencal, Frèdèric Mistral) were romantic to me at the time. But it wasn’t the kind of romance that made anything transcendent. Her pain for those she had lost, including a version of herself, were commensurate with her success as a poet, teacher and diplomat. Her poems were not salvation narratives; rather, they were fully immersed in both their anguish and their resoluteness in poetry-making itself. When I reflect now, I realize that the intimacy I felt that seemed so personal to me at the time was actually created through the poems’ specific locus and their energizing abstractions. It was the sense that all serious readers feel when they read good work: that the poet’s plight is your own. My own series of displacements in childhood began with my parents’ divorce in 1970s Northwest Arkansas when divorce was taboo at worst, and shameful at best. After relocating from a comfortable home in a small town to my maternal grandparents’ chicken and dairy farm, we moved to the nearby university town where we continued to change schools every two years. When my mother remarried, the displacement took on new characteristics in which my brothers and I learned in various ways that we were not valued, that we were burdens. It was this emotional displacement that complicated the geographical changes. It still translates all these years later like one loss blending into another. Alongside my early education of place, the graduate courses I took a decade later, with some notable exceptions, didn’t recognize me or my background. To paraphrase the poet Lucille Clifton, I had “windows” into other worlds through reading, but few “mirrors” in my education to recognize my own experience. The Southern towns and farm-scapes from where my language had grown and in which meaning and lyric were layered for me were dismissed as culturally impoverished. I sensed a dishonoring of my original places in the very place where I was learning to intensely read and write, a place where I was learning to teach other young people with even more invisible backgrounds than my own. Even with the privilege of whiteness and a certain kind of middle-classness, my lack of “mirrors” kept me from seeing myself as a serious writer and academic. But while I felt alone in my longing, I sucked it up, flattened my accent and embraced the urban North. My translation of the poem “Balada de Mi Nombre” (“Ballad of My Name”), stands out for me in its ability to inhabit both loneliness, the condition of being alone, and lonesomeness, that interior isolation that one feels no matter who they are with: My own name that I've lost, In this opening, the name has been lost to the speaker but still continues to live on in memory and the natural, sensory world. As the poem continues, we see the name personified; it is its own agent out in a familiar and beloved world to the speaker but apart from her. She, in turn, is a stranger to it: If without me, or if carrying away my youth, I love this poem for the way in which we see how profound the speaker’s isolation is. While the name is “lost” to her, it still lives on in this familiar world and fails to recognize the person who was, once upon a time, intimate with it. The speaker’s anguish at having others “tell” her that it walks “along the precipice of [her] mountain/ late in the afternoon” calls up deep loss and the pain of having to hear about it from others even as it still traverses the places that the speaker calls her own. The name has abandoned her without having abandoned the places she loves and the people she knows. The final line: “without my body and my soul roaming” can be read as both the name walking without her body and soul, but also as if “my soul roaming” is intrinsic to the name so that the name and her soul are companions, both lost to her. Years, jobs and a few geographies later, I found myself translating poems for an anthology of contemporary Chilean poets and this question of identity raised its head in a different way. I worked all through that fall and winter with a native-speaking colleague at my institution. Irma and I would often meet in her office filled with brilliant-colored wooden animals, Day of the Dead figures, crosses and wall hangings from Latin America and Spain—color exploding from every wall and shelf so that you couldn’t help but feel a little more joyful no matter what kind of day you were having. We would happily haggle over words in the poems we were working on until one day when I was struggling to translate a small, spare poem that contained the word “alma.” Unlike the nature of Mistral’s spiritual work, this poem was far more bodily and overtly sensual. We struggled over whether I should go with “soul” or “spirit” or “essence.” We questioned how to render “soul” into the English language when it has become a word that means everything from religion to philosophy to personality to food to music? It’s a word that in meaning so much has lost its flavor. It was a conversation and translation dilemma that lingered long after the anthology was published. In working on that anthology, what caught my imagination most was the work of the poet Sergio Coddou, and his poem “Soy un Hotel” (“I Am a Hotel”). It was a poem that felt like a homecoming as I translated: I am a hotel decked out to receive your laments with a room especially accommodated to shuck myself in your presence and you make of me sublime popcorn with the fire of your glance. There was a shock of joy in translating the word “desgranarme” (to shell) when I finally landed on the word “shucked.” It was a word from my childhood that was fun to say—even before I learned what it rhymed with. The softness of the “sh” along with the hard “ck” sound had such satisfaction. But just as much, it was the connection to home—shucking corn with its satisfying sough and ripping sound along with the curious and maddening silks that we had to pick off for our grandmother so she could boil the sunny husks. While the poem was an early love poem to Coddou’s wife Rosario, it also had such a wonderful sense of place in its language and conceit. It was so beautifully raw and imaginatively romantic that I sent Coddou a message to see if he would let me publish my translations of his work in literary journals. When he told me he liked how I had rendered his work into English, especially the sound, it began an ongoing conversation. Then one winter night a few years after our initial email exchange, Coddou and his family were visiting Manhattan, and they invited me to dinner. I arrived at their Airbnb on the Upper East Side with a backpack full of cookies for the kids and a bottle of wine for him and Rosario. It was one of those New York City nights that smelled of snow. We had dinner in the spacious and warm apartment with their four children, who were clearly accustomed to their parents’ friends at dinner as evidenced by their courtesy and friendly ease. Dinner was followed by one of those conversations—full of art and poetry, Chilean politics and family history—which I relaxed into, never wanting it to end. Rosario told me that when he showed her that poem—the same poem that I had been so taken with—that’s when she knew “he was serious” about her. Our conversation continued as I told them about the process of translating the poems for the Chilean anthology those years before and, specifically, the struggle over the word “alma.” I told them about the dilemma of the English and how to go with “soul” was to invite religious or heavily philosophical baggage, while “essence” suggested the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. So how could I do justice to the translation? The moment became especially vivid when Rosario touched her pointer finger to her tongue, marked the air with it, and said, “That word… it has a little bit of soil in it.” She explained that the word is connected to the land, to a specific place. It was one of those moments that stunned me in its brilliance. Why hadn’t I thought of that? After all, the word’s etymology came in part from the Arabic “al-ma,” meaning “on the water.” Her insight had concretized the word, turning it beyond the religious or the psyche and into locus—the place where things happen. It was a moment in which I had the profound glimpse at how embedded our language is in our place of origin. What she knew couldn’t be fully discovered in a book, but it felt deeply and intuitively accurate. There we were around a warmly lit table, the leftover dishes pushed to one side, the wine half-gone, several stories above the city where anything anyone might imagine was whirling around us like the snow that would come in the early hours of morning. In that extraordinary conflation of conversation, revelation, people and place, an intimate moment had occurred, a moment within a night that felt like my best experiences of translating. The most brilliant moments come unexpectedly and indirectly. I learned that while I wanted to be faithful to the original language of the poet, I discovered that what was really after and what I found was the spirit or genius loci within the poem’s stanzas and spaces. Lea Graham is the author of two poetry collections, From the Hotel Vernon (Salmon Press, 2019) and Hough & Helix & Where & Here & You, You, You (No Tell Books, 2011); a fine press book, Murmurations (Hot Tomato Press, 2020), and three chapbooks, Spell to Spell (above/ground Press, 2018), This End of the World: Notes to Robert Kroetsch (Apt. 9 Press, 2016) and Calendar Girls (above/ground Press, 2006). She is the editor of the forthcoming anthology of critical essays: From the Word to the Place: The Work of Michael Anania (MadHat Press, 2021). She is an associate professor of English at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, NY and a native of Northwest Arkansas. You may also like reading Dust in the Sunlight: Translating Light by Steven Teref and Maja Teref. I just cannot believe that my gallery, "Working On Gallery", is turning a year old! There were so many wonderful guests who talked about their crafts & writing processes from Summer 2020 - Summer 2021. Now, I have a list of new guests. They are all amazing poets, writers, translators, and editors. I am so excited to read and learn from their essays. Ananda Lima Chloe Martinez Hasanthika Sirisena Jamia Weir Josh O'Neil Kylie Gellatly Lea Graham Tanja Softić Moreover, one of RHINO Poetry's popular segments, RHINO Poetry *graphic* Review, will be out in September. This issue will be our third anniversary of *graphic* edition. All reviewers are experienced poets who also work with visual elements in their publications. It is going to be another phenomenal issue. Featured reviewers are: Aaron Caycedo-Kimura Anthony Madrid Chloe Martinez Crystal Simone Smith David Morgan O’Connor Frances Cannon Ina Cariño Jennifer Steinorth Kelly Cressio-Moeller Meg Reynolds Rodney Gomez Tricia Lopez * I will also have lectures and live reading events. The current (on-going) event is a 3D virtual graphic poetry exhibition at Kunstmatrix. Thanks to Tupelo Press, admission is free for all audiences. |

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024