|

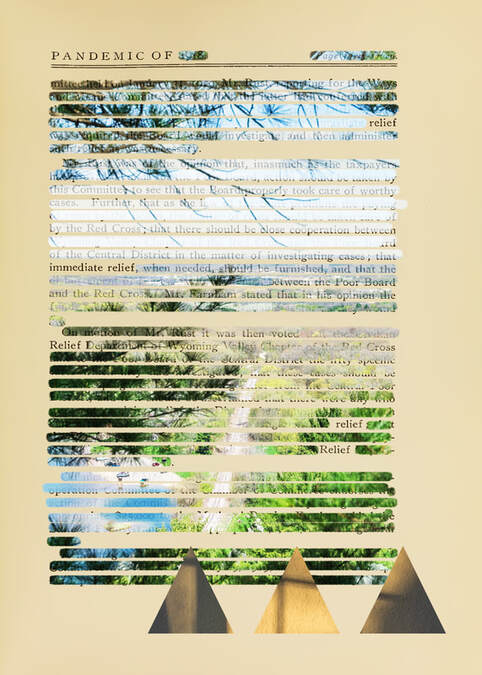

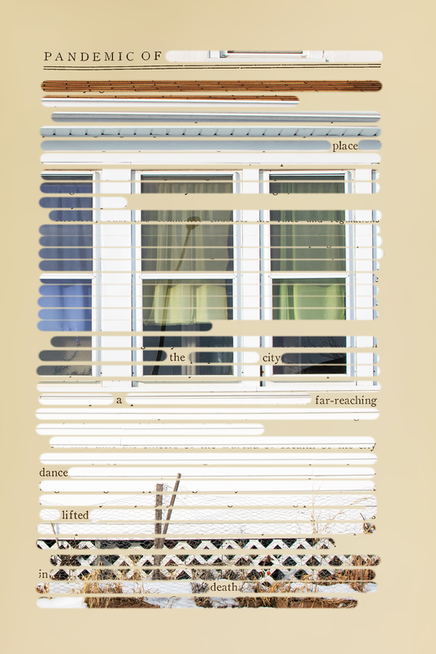

The first time I saw Kelsey Zimmerman's erasure poems at Indianapolis Review, I immediately contacted my dear friend Natalie Solmer, and I asked her to introduce Zimmerman. I sensed new elements of visual erasure poetry from her work, but I couldn't pinpoint exactly what they were. Her poetry erasure technique is similar to other erasure poets (erasing words from an intriguing original text), but something stood out and captured me. Coincidentally, this was around the same time I was discussing and observing erasure poems with students at Northen Iowa University. I eventually created a study guide for Visual Erasure Poetry, and in it I wrote Zimmerman has advanced versions of visual erasure poems that we were currently familiar with. I was glad that Zimmerman shared her creative process because it identified what I was seeing as new to visual erasure poems. Her work was indeed moving forward based on what we knew about visual poems - - she was inspired by many poets & artists such as Douglas Kearney, and then she created her erasure poems using new computer tools and existing photos that she took. Now, I understand how her vivid colors (she uses monotones, but those colors stand out) were adapted, and how she thoughtfully coordinated texts & images. There are new elements that uniquely signify her work. This is both unexpected and thrilling, and I seriously enjoy being in the front row of this visual poetry renaissance. YouTube by Douglas Kearney, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Octavio Quintanilla and Jennifer Sperry Steinorth. By Kelsey Zimmerman In March 2021, I attended an AWP session online that pushed me for the first time towards visual poetry. Compounding the Line: Visual Poetics in a Word Doc World with Douglas Kearney, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Octavio Quintanilla and Jennifer Sperry Steinorth. For some time, I’d been thinking about ways to integrate the photos I take with poetry and hadn’t been able to identify a method that didn’t feel tacky somehow—my worst fear was creating something that made someone think, “Looks like that was done in Canva!” But the examples of these amazing artists in this session reinvigorated this quest for me. Douglas Kearney shared a video of some of his process while working with Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator that, in particular, opened my eyes to the possibilities there if I could improve my comfort with the software – I was a novice, but already comfortable with Adobe Lightroom Classic and InDesign. The cross-platform functionality of all Adobe programs is somewhat similar, and my knowledge of the latter provided a much-needed entry point. Around that time in March, I was also in a poetry workshop in my MFA program that centered on the performance of poetry, not just as it’s spoken aloud, but how it performs on the page. I began to integrate that idea into my “normal” poetry, but also began to spend much more time thinking about how visual elements could perform on the page and what exactly I wanted any visual poetry of mine to say. I also read Hotel Almighty by Sarah J. Sloat, which proved highly influential, and a friend introduced me to Nets by Jen Bervin, Emily Dickinson’s postcard poems, and several other books on the history of concrete and visual poetry, and explored the work of several small presses, Ugly Duckling Presse in particular (and UDP is now very high on my list of dream publishers, given the esteem in which I hold their work!). Another friend had worked with Katy Didden at Ball State as an undergraduate, and her Ore Choir was another inspiration. Trying to situate myself into the context of the arena I hoped to enter was both daunting and inspiring: there was my little myopic self, surprised on some level that so many other people had worked to solve this same problem, make art in this same vein. All their work proved to be instructive and inspirational. I often think of my creative process as a sort of machine, or maybe an animal, where I go through weeks or months of input input input input, voraciously reading and exposing myself to ideas, and at certain points I sit down and switch to output. So I had all these things floating through my brain and had some half-formed ideas floating around, and there was one thing on my brain that superseded most other thoughts, and those were thoughts on the pandemic. The idea for how I would make an erasure poem of poetry had come to me, but I had to have the right text and the right images. Luckily, I already had a catalog of thousands of my own photographs to choose from. But for those initial text scans, I turned to archive.org and searched “pandemic.” That’s how I found the text for these works in The Indianapolis Review. A small tome, digitized in the infernal magic of the internet, on the 1918 flu response and vaccination, in the public domain on the Internet Archive. As far as page selection goes, I choose the ones I make erasures from more or less at random: I do scan the page for content, looking for words I think I can work from, words that interest me and spark something – I also especially like pages with ornamental designs (such as chapter openings in some books) and lots of white space (such as on chapter-ending pages). These allow for an extra dimensionality, another way of letting the original work speak for itself and highlighting what it says in a new way. The examples of my work in The Indianapolis Review are from the very first time I sat down to ever seriously try to create something like this. It’s fascinating to look back because, while I still like them, there are definitely things I’d do differently now – especially when it comes to figuring out ways to make the text flow more easily and stand out -- though in these pieces that the text and imagery battle for first relevance is a feature, not a bug. There are thousands of photographs in my catalog, and after skimming a page I’d picked to be an erasure, I comb through all those photos for one that seems like it would capture the right mood. From there, it’s all listening to the combination of words and image within the project, letting the final form reveal itself. Since March I’ve found it’s extremely difficult to find high-quality scans online, even on websites like archive.org or Project Gutenburg. Or if you can find them, they sometimes have restrictions associated with the file types or the scan quality as low. I take my own scans now, with books of my own or interesting ones I find at estate sales or thrift stores. In the meantime, I’m continuing to make more erasures in this vein, but am also always trying to think of what to do next. There’s always some boundary to be broken. Kelsey Zimmerman is a writer and visual artist from Michigan currently living in Iowa. A 2021 Best of the Net nominee, her work is published or forthcoming in Hobart, The Indianapolis Review, Nurture: A Literary Journal, and Ghost City Review. You can find her on the web at www.kelseyzimmerman.com or on Twitter @kelseypz.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024