"Words fail, translations fail, but form transcends—image makes meaning no matter the language."11/1/2023

I met Danielle Pieratti when we were classmates at the Bread Loaf Translators' Conference. Some people asked why I did not choose Asian or ekphrasis lectures because I wanted to learn Italian translation processes.

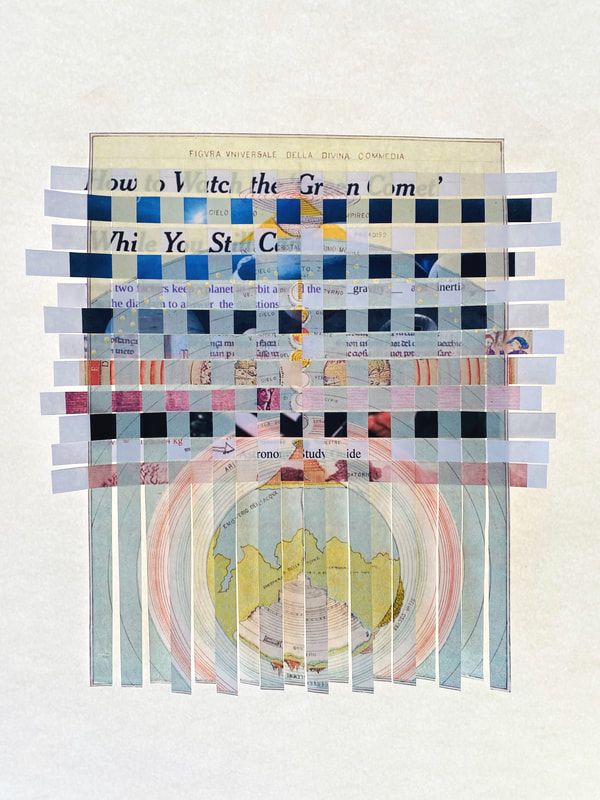

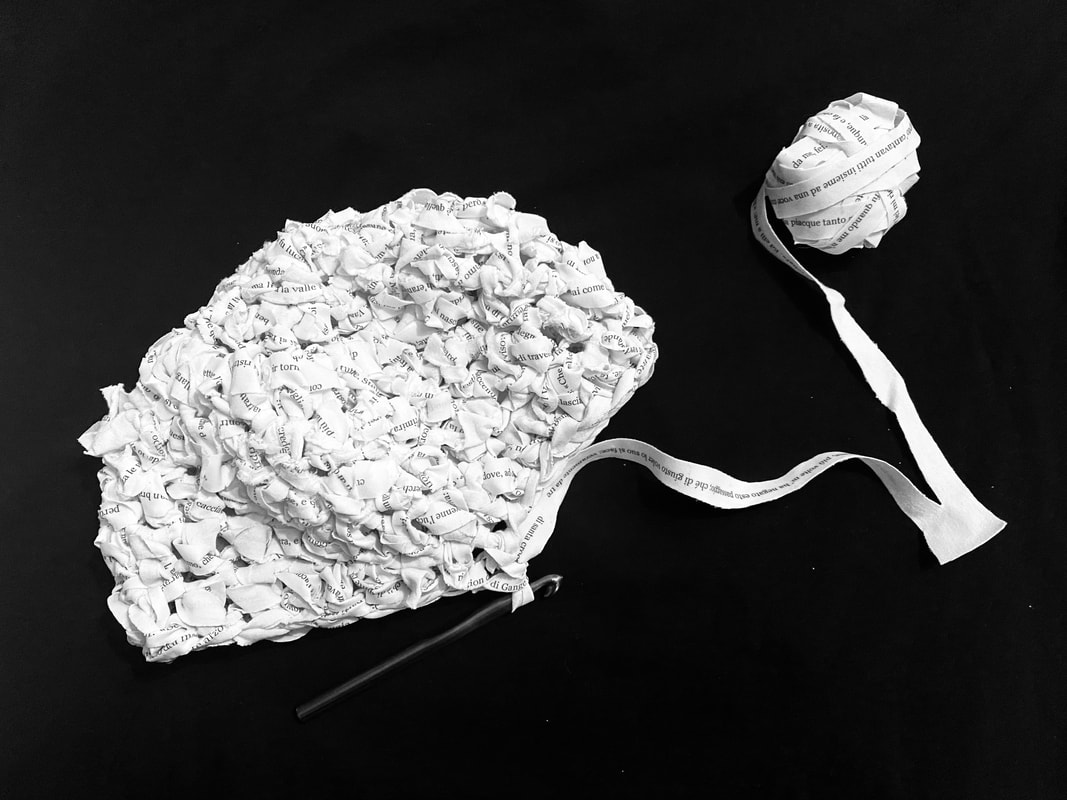

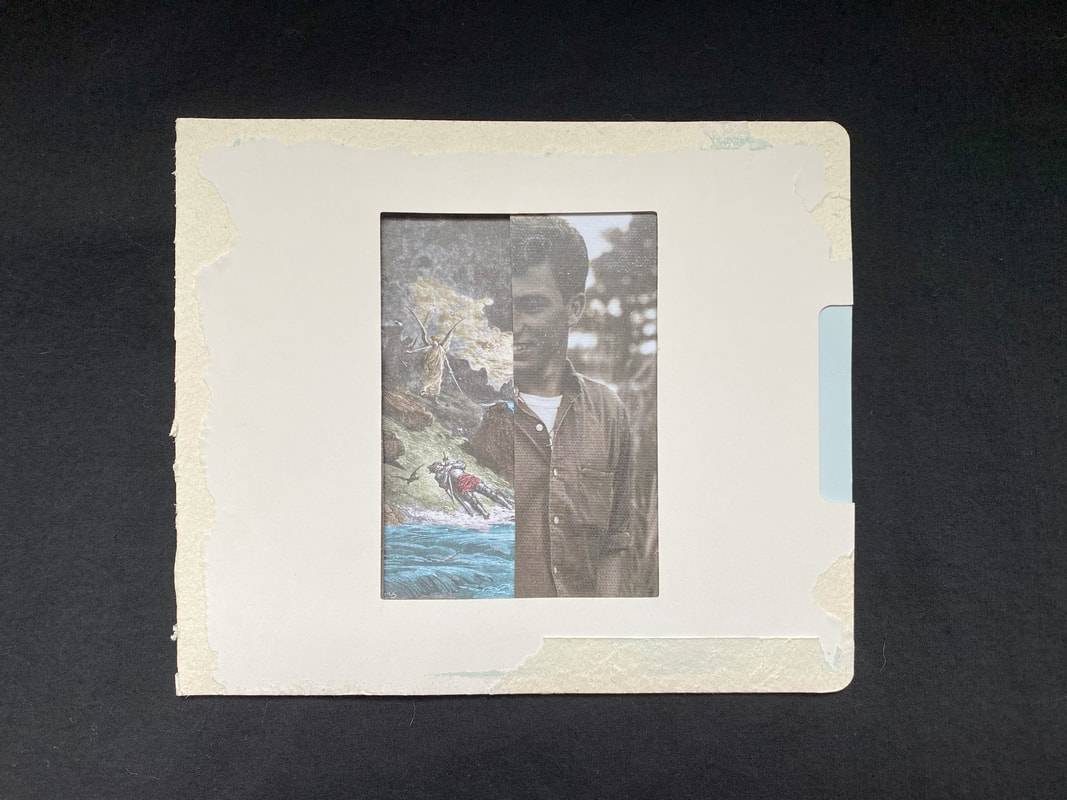

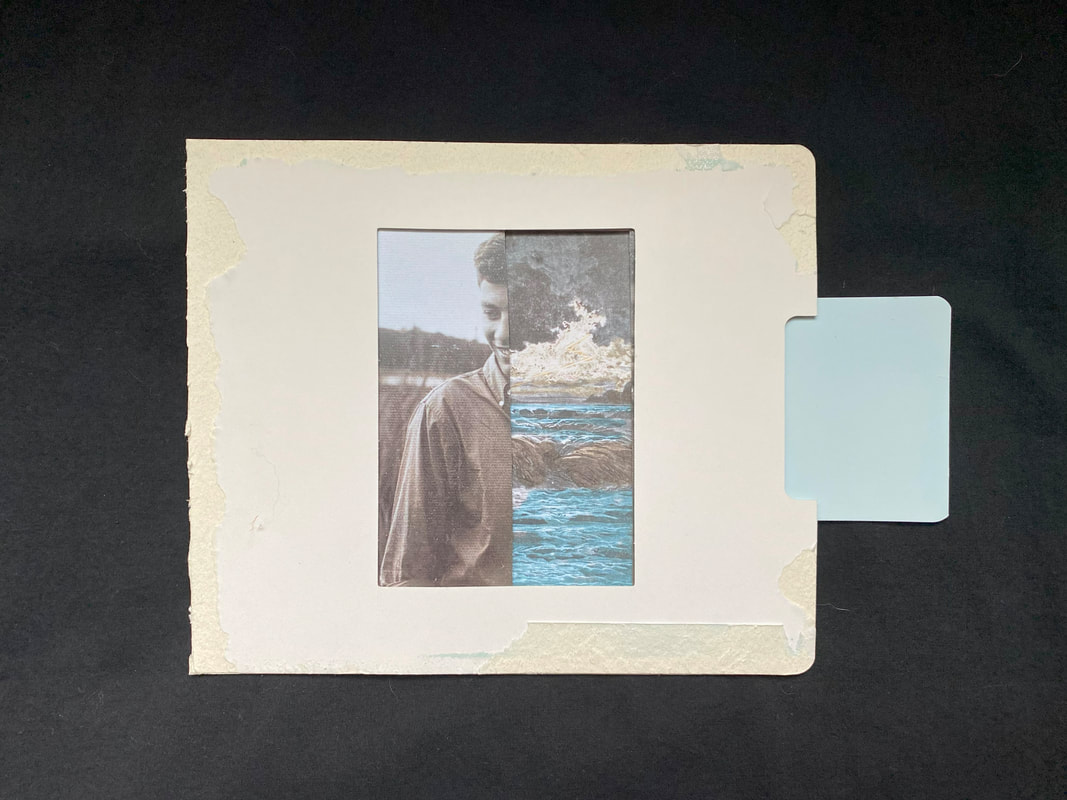

I thought that the Italian concepts of culture and language might be similar to those of 7th - 11th century Japanese literature, which was my project at the conference. I wanted to observe how Italian translators approach interpreting original Italian ideas into English. I was so glad my instinct was correct because I met top notch Italian translators there. Danielle Pieratti translated Laura Pugno's Sirene - - poetic, yet dark and strange hybrid cultures of east and west - - at Bread Loaf. The story has a futuristic fictional setting. It could be a cool graphic novel, but this translation is full of poetic instances and does not have any illustrations. "If the act of translating constitutes a violence, the incorporation of visuals comes to constitute a rejection of language akin to embracing untranslatability." - - Danielle Pieratti I started understanding her creative philosophy when I read her process interview today. She talked about her new translation project. Dante’s Purgatorio is the perfect text to experiment in-between. If ekphrasis is a literary description of art, we may be able to reverse or expand. Pieratti's process is a visual description of translation and its original text. Again, I realized that translation itself is an act of creativity. The poems I’m currently working on trouble the boundaries between translation and originality by borrowing a significant portion of their language from English translations of Dante’s Purgatorio. I started working on this project in November of 2022, just a few weeks after my son, then 12, was diagnosed with leukemia. It seemed then that the relatively short-term sacrifices we’d have to make to ensure his positive long-term prognosis had landed us in a kind of limbo that only exacerbated the bleak holding pattern that for many has characterized the years since Covid. In my attempts to process both, I found myself turning to visuals each time I struggled to synthesize through language. It had already become clear that working in a hybrid space on a “derivative” work was going to require some visual flexibility; in a bilingual work of translation, facing pages are usually presented as equivalents of one another, and I began by experimenting with that construct. In the process of considering how I wanted readers to interact with a hybrid collection I started thinking about the ways reading, writing, and translation might be figured materially, not least because each had begun to resonate more fully than ever with what was going on in my home life. There are experiences that leave nothing in your life untouched, so that even banal activities—driving to work, cooking dinner, reading, knitting—all begin to take on new, interdependent meanings. I wanted to capture visually the synthesis between, for example, a rare astronomical event, a homeschooled unit on astronomy, and a canto from Purgatorio in which Virgil teaches Dante about the stars. In return, the visual experiments gave me new points of entry into my written work. I think working in multiple languages broadens one’s understanding of what a language is and can be. This is a cliché notion, of course—languages don’t have to be verbal, and translation has been applied as a metaphor to all kinds of communication, linguistic or otherwise. But poet-translators in particular have made frequent use of visuals in hybrid works. I’m thinking of Anne Carson, whose translations make stirring, sometimes playful use of visuals, and Don Mee Choi, who presents photography as just one of many types of translation (and non-translation) in her work. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Cecilia Vicuña’s Instan, and Divya Victor’s Curb are other examples of translingual works—works that stage, highlight, or reflect relationships between and across languages—that incorporate visual language as one among many. If the act of translating constitutes a violence, the incorporation of visuals comes to constitute a rejection of language akin to embracing untranslatability. Words fail, translations fail, but form transcends—image makes meaning no matter the language. I’ve found this to be true not only as a poet beginning to experiment with visual poetics, but as a reader observing that the most striking imagery retains its power no matter how it’s translated. A new way to figure translation that I’ve begun to experiment with is the movable page. Movable books were common during Dante’s era, and today’s most obvious iteration is the pop-up book, which makes use of constructions like moving tabs and volvelles to reveal or conceal meaning. I want these new visuals to play with the idea of equivalence and replacement—translation as a shadow (to use a frequent image from Dante) that either conceals or is concealed by the source text, emphasizing the power dynamics between the two by disallowing simultaneous versions to coexist. In this respect the movable components comment on the politics of translation but also on the stakes of translingualism, which often reflect the complex, sometimes painful varieties of linguistic masking and/or passing that navigating between languages can require. Even my own unencumbered experience of multilingualism still reflects familial and historical pressures that heavily impact my linguistic identity. My father’s name was Arno, and he’s pictured below, alongside an illustration of the Arno River—the Florentine waterway beside which Dante claims, in Inferno 23, to have been born, and which features intermittently in his Commedia. My father was born in the Bronx, but during the years we lived in Italy his immaculate Italian marked him easily as a native, even in professional settings. He died of cancer in 1997, his Italian forever calcified into the dark mythology I preserve for him. Our son, Luke Arno, is named after him. Danielle Pieratti is the author most recently of Approximate Body (Carnegie Mellon University Press 2023). Her first book, Fugitives, (Lost Horse Press 2016) was selected by Kim Addonizio for the Idaho Prize and won the Connecticut Book Award for poetry. Additional honors include The Paris Review's Bernard F. Conners Prize, as well as fellowships from the Connecticut Office of the Arts and the Bread Loaf Translators' Conference. Transparencies, her translated volume of poems by Italian poet Maria Borio, was released by World Poetry Books in 2022. Danielle is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Connecticut, where her work merges contemporary poetry, literary translation, and translingual writing studies. Support Working on GalleryYour $25 donation will be a tremendous support for Working on Gallery's future guests and running costs. If you become a patron, your name will appear in the next Working on Gallery's article. In addition, you will receive my first poetry book, "Where I Was Born", for U.S. shipments. Or, you will receive a thank-you letter for international shipments. Working on Gallery has been used by universities, advanced-level art lectures, and writing workshops. Your donation will help this gallery be more successful. Thank you so much - Naoko Fujimoto Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

|

フジハブ

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

Welcome to FUJI HUB: Waystation to Poetry, Art, & Translation. This is not your final destination. There are many links to other websites here, so please explore them!

What are you looking for?

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024

FUJI HUB Directory

Popular Sites:

Gallery of Graphic Poems

Working On Gallery

(Monthly New Article by Writers & Artists)

About Naoko Fujimoto

Contact

Naoko Fujimoto Copyright © 2024